What the report aims to do

3 The DfES has stated that 'Public Private Partnerships (including the Private Finance Initiative) can provide the public sector with better value for money in procuring modern, high-quality services from the private sector' (Ref. 1). More specifically, the anticipated advantages include:

• Better value for money (VFM): The private sector is expected to deliver projects quicker and at lower unit cost with less risk to the public purse, especially because the same PFI provider is designing, building and then operating the facility - known as 'design, build and operate (DBO) synergy'. Because the PFI tendering process is undertaken on the basis of an output specification of service requirements incorporating building design and services standards, rather than a prescriptive input specification, the private sector has more freedom to innovate, which should lead to better quality at a lower cost - the DfES has stated that 'the private sector gets the opportunity to enter into long-term contracts which are defined in terms of outputs, so maximising the scope for innovation'. 'By using private sector skills and expertise in this way, the public sector can secure better value for money than through traditional procurement' (Ref. 2).

• Buying services, not things: PFI changes local authorities from being managers of buildings into purchasers of services provided by private companies. Rather than purchasing a building, with central or local government responsible for the upkeep, PFI provides serviced accommodation that is paid for only when it is delivered to the required standards.

• Better risk management: Better VFM should be achieved if risks are allocated to the party most able to manage or pre-empt them. In the case of a new school, for example, the risk of a structural problem in the building should be transferred to the PFI provider that has a long-term stake in the building and therefore has the incentive to design and build the school in a way that minimises structural defects.

• Long-term legacy: Unlike other school-related funding, such as for teaching, ear-marked funding for building maintenance is ensured for the 25- to 30-year length of the contract and is thus protected against the uncertainty of possible public sector budget cuts in future years. This should lead to a more sustainable, long-term built legacy.

4 Clearly, since the number of PFI schools fully operational is still small and the proceurement arrangements are relatively new, these anticipated benefits of PFI are not yet proven in relation to schools. The purpose of this report is to review what PFI in schools had delivered by the end of 2001 - and how users were experiencing those schools during the first half of 2002 - in particular, by comparison with traditional procurement. We examined whether the first round of buildings were of good quality, what the schools' users thought about the buildings and services, and their cost. I At this stage, therefore, we were able mainly to look at the early evidence for the first two of the four anticipated benefits just described.

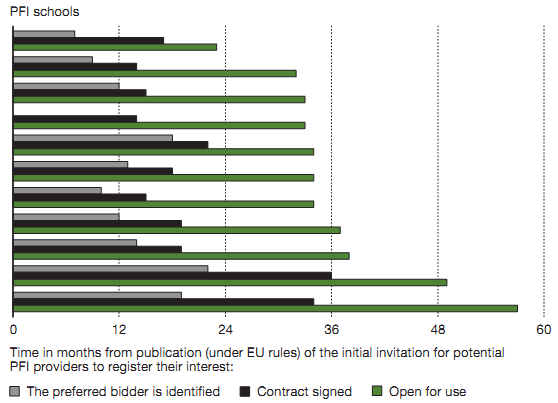

5 When considering the evidence, it is important to recognise the gestation time between first planning for a new school, and when it is open for use. Before 'Expressions of Interest' are invited from the private sector under European Union public procurement rules, a local educational authority (LEA) has already undertaken an options appraisal, developed an initial output specification and an estimate of hypothetical costs were a traditional procurement route to be followed. Although there is then room for the design and cost to change (otherwise there would be no opportunity for the private sector to attempt to deliver innovation), in practice the overall cost and some of the design options have begun to be fixed. The outputs being delivered now will reflect the procurement process and skills existing some while before the new school opened: the planning for the schools that we visited during 2002 began in the late 1990s [Exhibit 1 and Box A, overleaf]. More recent schemes may have already learnt lessons from the pioneers, and from changes in policy and process. We return to this issue in the last chapter. In addition:

• school PFI contracts typically last for 25 to 30 years. Since even the oldest PFI school had been open for only two years at the time our research was conducted, it will be some time before a complete understanding of the impact of PFI emerges; and

• during fieldwork, we visited two-thirds of the completed and operational new-build PFI schools in existence. However, there were only about 25 such PFI schools in England and Wales at the time of our fieldwork in spring and summer 2002, and some of those had not been open long enough to be included in the research.

Exhibit 1 | |

The planning for the schools that we visited during 2002 began in the late 1990s. | |

PFI schools | |

| |

Source: Audit Commission, based on LEA documentation and visit information | |

Box A | |

1997 | Statement of case for new school to DfEE. Provisional government approval. |

1998 | Options appraisal, including first cost estimates and definition of type of facilities and services wanted. Outline Business Case (OBC), including a comparison with the hypothetical cost of procurement via traditional means, approved by the council and submitted to DfEE. Provisional central approval for PFI route. Expressions of Interest from the private sector invited via Official Journal of the European Community. 'Long-list' of bidders selected from responses received and initial project submissions invited. 'Short-list' selected and priced bids invited. |

1999 | 'Best and final offers' invited. Preferred bidder identified. |

2000 | Planning permission granted. Design, construction and operation cost freeze. Contract signed. Work commenced. |

2001 | School opened. |

Source: Audit Commission, based on LEA documentation and visit information | |

6 We have drawn on a broad range of evidence, including interviews with those involved in setting up schemes, financial data, building quality surveys and questionnaires completed by users of new buildings [Box B, overleaf]. | |

| |

Box B | |

The LEAs and schools for each aspect of the study were randomly sampled and reflected a rural/urban and geographical balance, and a similar range when compared with the national distribution of schools' sizes (pupil numbers) and pupil ages. We drew the sample of traditional and PFI schools, wherever possible from within the same LEAs - given the recent history of funding, inevitably the sample of traditional schools was slightly older than the PFI sample (the traditional schools opened between 1997 and 2001; the PFI schools between 1999 and 2002). Fieldwork The Audit Commission team visited nine LEAs across England and Wales with PFI schemes that had been delivering FM services for close to a year or more. Local authority and school staff were interviewed in conjunction with private consortia members. User views about quality MORI administered a questionnaire on our behalf, based on a design evaluation tool developed by the Construction Industry Council (CIC), to a range of teaching and support staff and older pupils in 18 new-build schools - ten traditional and eight PFI, including a mix of primary and secondary schools. In total 95 users were interviewed (35 in PFI schools and 59 in traditional schools). Building quality, DBO synergies and whole-life considerations The Building Research Establishment (BRE) assessed the quality, on our behalf, of ten traditional and eight PFI schools against recognised benchmarks and accepted good practice; eight of the traditional and five of the PFI schools were included in both the MORI and BRE surveys. In total, therefore, the two externally assessed aspects of the research contained 12 different traditional and 11 PFI schools, with the fieldwork visits bringing the total number of new-build PFI schools covered in the research to 17. Costs The capital costs of replacement and new-build PFI schools were collated from LEAs and private contractors, including the costs of contract variations where possible. These costs were then compared with the outturn costs of traditionally financed schemes. Costs were adjusted to enable, as far as possible, like-for-like comparisons. For facilities management costs, data on existing schools was obtained from an existing Audit Commission database of actual running costs for over 5,000 schools. The projected running costs of PFI schools were obtained from LEAs or PFI providers. It must be emphasised that this information is based on self-report and is, of its nature, not actual expenditure - it should be interpreted with caution as the only information available to us at this time. (Chapter 4 discusses further the potential difficulties of a developing 'information gap' for LEAs and schools.) Other data: affordability, VFM, competition, numbers and types of schemes Data were collected from the final business cases (FBCs) for operational schemes. The Public Private Partnerships Programme (4ps) database of projects was made available to us, and the PFI report database accessed (www.publicprivatefinance.com/pfi). The DfES and Welsh Assembly Government also supplied data on the number of PFI schemes and their costs. Source: Audit Commission | |

__________________________________________________________________________________

I The Commission has previously reported more generally on capital expenditure, and on management of the PFI procurement process (Refs. 3 and 4).