Technical quality

| 11 Experienced construction professionals from BRE assessed schools against five 'design quality matrices' specific to school buildings. The matrices covered a wide range of individual elements of building quality, including whether the architectural design made the best use of space and was innovative; temperature, light and acoustic qualities; and the quality of materials and furnishings and their likely long-term maintenance costs. Where appropriate, the measures used published standards and guidance from, for example, the DfES, Building Regulations and the Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers (CIBSE). 12 Overall, BRE found that the quality of all the schools, however funded, fell below 'best practice' [Exhibit 2a, overleaf]. The quality of the PFI sample of schools was, statistically speaking, significantly worse than that of the traditionally funded sample on four of the five matrices [Exhibit 2b, overleaf]I. There were no significant differences between primary and secondary schools. 13 Taking the different matrices in turn, the main findings are: • Architectural design: The difference between PFI and traditional schools was particularly marked in external architectural merit - one of the six elements that make up this matrix (an average score of 1.8 compared with 3.0). This measure is not solely about aesthetic merit, but includes an assessment of type of materials and whether there was adequate shelter from rain and sun. BRE found few examples of innovation, and these were confined to the sample of traditionally funded schools. For example, BRE described one such school as: Probably the most imaginative architectural design visited. The curving roofs clad in cedar shingles represent waves, a suitable nautical symbolism this close to the sea. They also make for dramatic interior spaces and aid daylight strategies with clerestoriesII under the 'crest of the wave'... An exemplar primary school... • Building services design: Across the whole sample of schools, assessments were worse on this matrix than any of the other four matrices - indeed none of the 18 schools scored better than 2.3 (out of a 'best practice' possible score of 4.0), with the worst schools scoring only 1.4. Overall, there was little difference between schools built under the different procurement routes, but the crucial area of architectural integration was assessed as better in the sample of traditionally funded schools. For example, in one traditionally funded school: Traditional materials with features such as brick chimneys encasing boiler flues and triangular 'dormer' windows to the sports hall give the building a feeling of domestic scale entirely appropriate to a primary school. • User productivity: Audible and visual intrusion, acoustics and air quality were on average better in the traditionally funded schools sample. |

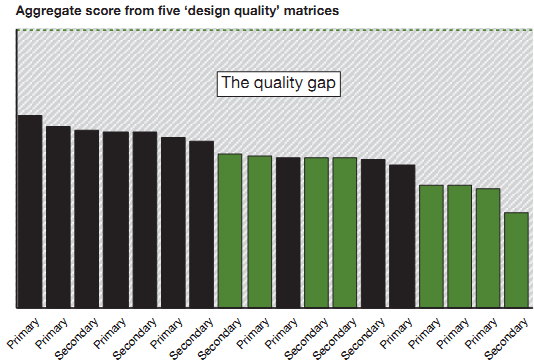

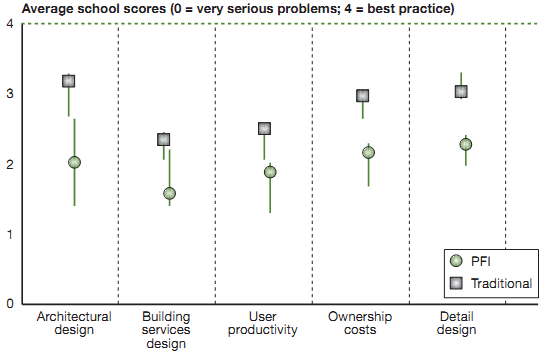

| Exhibit 2 (a) Aggregate scores for the individual schools: the quality of all the schools, however funded, fell below 'best practice'. (b) Average performance on each of the five matrices: the quality of the PFI sample of schools was, statistically speaking, significantly worse than that of the traditionally funded sample on four of the five matrices. To reach the level of 'best practice' on the matrices, a school had to meet all of the DfES and other relevant guidance. |

Despite the small number of PFI schools in existence and involved in the research (the sample included 8 of the 25 or so already built and operating in spring 2002), the difference between the traditional and PFI sample was statistically significant overall (Kruskal-Wallis test of the equality of medians, p < 0.01 - there is less than a 1 per cent likelihood that the difference was due to chance) and on four of the five matrices. The squares and circles in Exhibit 1b plot the average score on each matrix for the sample of traditional schools, and the sample of PFI schools. The vertical bars show the variability about these averages (the 95 per cent confidence interval). PFI and traditional schools are of significantly different quality if these bars do not overlap - that is, one type of school was assessed to be of higher quality and the difference is unlikely to be due to chance. On four of the measures, the bars do not overlap, and traditionally funded schools score better than PFI schools. On one measure - services design - the bars overlap, showing that the difference between the two types of school on this aspect of quality was probably more apparent than real. Source: Audit Commission analysis of data supplied by BRE for eight PFI and ten traditionally funded schools |

|

• Ownership costs: Exterior materials and internal fabric and finishes with lower costs of ownership were more frequently chosen for traditionally-funded schools. For example, in one PFI school, assessors stated that the 'choice of paving flags as a floor finish is unfortunate, as they are wearing badly and are stained and cracked.' The best examples of the type of innovation that can improve fitness for purpose and minimise running costs over a school's lifetime came in traditional schools within LEAs with a long-established track record of excellence in school design. • Detail design: The final matrix reviewed external, internal and junction details (all of which were on average better in the sample of traditionally funded schools), furnishings, fittings, safety and security. Rectifying and coping with failures will increase maintenance and occupancy costs, which will fall to the PFI provider if they are covered by the contract output specification (as discussed later in this chapter). | |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________

I Deficiencies in the design of some early PFI schools have also been identified by the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (Ref. 7).

II Clerestories are the upper part of a wall that contains windows.