Value for Money Analysis and Other Valuation Tools

Consideration of the PPP option can be fraught with emotionally charged ideological rhetoric, but this debate can be informed by well-defined and executed business case analysis. Value for Money (VfM) calculates the difference between the costs and benefits associated with both traditional and PPP procurements. Some of the benefits to developing a financial model to evaluate PPP proposals include (Oakley 2008):

• Helps establish the business case for a PPP,

• Provides important insights about the project's ability to obtain financing,

• Allows for testing of assumptions (e.g., toll increases, traffic growth, length of agreement) early in the process, and

• Provides a method for "optimizing" the transaction and encouraging competition and innovation.

The VfM analysis has been widely used outside the United States, particularly the United Kingdom. Our state DOT survey confirms that the availability and consistent application of evaluation tools, such as VfM, are important to state decision making. Of the nine states that have at least one PPP project in place, two (22%) have not used VfM, and four (44%) reported using VfM frequently. The preliminary results of a survey of VfM analysis tools in the United States conducted by Morallos and Amekudzi (2008b) showed that only one-third of the states use VfM or similar tools to evaluate PPPs. Florida, Virginia, and Oregon reported using VfM.

Texas has used a process called "shadow bids" for two PPPs. These involve the state, through its own resources and consultants, making detailed estimates of design and construction costs, operating costs, and a detailed financial model (GAO 2000b). The results of the shadow bids are compared with the private sector proposals. In addition, the moratorium bill passed in 2007 (SB 792), requires the Texas DOT to conduct a "market valuation" analysis for new toll roads to assess how much value a facility might attract from the private sector.

An International Technology Scanning report by the FHWA documented best practices regarding audit stewardship and oversight of PPPs in Europe (Jeffers et al. 2006). The report indicates a need for personnel with skills, including value engineering, business modeling, capital budgeting, traditional financial problem-solving methodology, and performance auditing. The report concludes that a state DOT team should develop a public sector comparator (PSC) and a business model for each PPP opportunity to determine whether the project can return VfM to public.

Grimsey and Lewis (2005) and Morallos and Amekudzi (2008a) have thoroughly explored the VfM concept. Although cost-benefit analysis is widespread, there are few examples of VfM in the United States, largely because of the limited experience with PPPs. British Columbia, the United Kingdom, and Victoria, Australia, have made PPP/public procurement decisions for many projects using VfM analysis and have established set procedures for its calculation. Table 4 provides a list of some of the publicly available guides for VfM analysis.

An estimate of VfM is achieved by calculating the present value of the PSC and then comparing it with one or more bids from private companies. The PSC examines life-cycle project costs, including construction, operations, maintenance, and additional improvements that will be incurred over the course of the concession term (GAO 2000b). To prepare the PSC, the sponsoring agency needs to define the project scope in advance to the extent that a realistic determination of what project requirements, costs, and revenues are likely to be. This may involve the following actions:

• Develop greater understanding of project geotechnical and site conditions through advanced reconnaissance;

• Advance project design to the point where there is a clear understanding of the key attributes of the project design and functional characteristics;

• Perform advanced value engineering to ensure that the most cost-effective design parameters are considered;

• Revise assumptions typically used to estimate traffic volume and revenue potential, especially the possible size and frequency of toll rate changes when tolling is involved to reflect current fiscal concerns;

• Recognize the risks inherent in the inflationary effects on the costs of project materials (AECOM 2007b); and

• Consider value of speed in construction execution associated with minimizing public inconvenience.

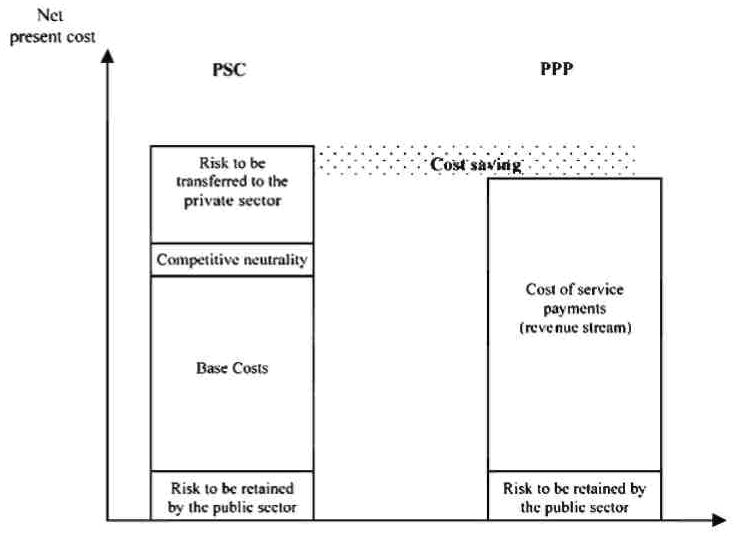

Once the characteristics of the project are better understood, the PSC is constructed using four components:

1. Raw PSC is the discounted cash flows of benefits and costs attributable to the project assuming no private sector involvement. Cash flows are discounted by a rate reflective of the government's time value of money plus a systematic risk premium for risks inherent to the project. Costs include direct and indirect costs and are reduced by third-party revenues including user charges, increased demand for a facility or service, or payments received by third-party use of the facility.

2. Competitive neutrality value removes inherent competitive advantages or disadvantages of a government agency compared with the private sector. This value is added to the PSC to allow for comparison with the PPP

option. For example, public sector advantages include exemptions from land taxes or other taxes and fees that would otherwise be levied from a private investor. On the other hand, public sector disadvantages may include political risks or economies of scale that would allow the private sector to operate more efficiently.

3. Transferable risks are those that are likely to be transferred from the procuring agency to the chosen private partner(s). The risk valuation includes estimating the probability of the risk occurring, and could be a simple estimation of an amount above or below the raw PSC, or the application of Monte Carlo simulation using a probability distribution of risk.

4. Retained risks are those risks that the public partner will retain. The present value of retained risks will also be added to the cost of the private bids to reflect the true cost of the PPP options.

TABLE 4

VALUE FOR MONEY GUIDES

| Country | Document | URL |

| United Kingdom | HM Treasury, Value for Money Assessment Guidance (Nov. 2006); Value for Money Quantitative Assessm ent User Guide (Mar. 2007) |

|

| Canada | Industry Canada, The Public Sector Com parator: A Canadian Best Practices Guide (2002) | http://strategis.ic.gc.ca/pics/ce/ic_psc.pdf

|

| Victoria, Australia | Partnerships Victoria, Public Sector Comparator (2001); Public Sector Com parator Supplem entary Technical Note (2003) | http://www.partnerships.vic.gov.au/CA25708500035EB6/0/C0005AB6099597C2CA2570F50006F3AA?OpenDocument

|

| Ireland | Central PPP Unit, Value for Money and the Public Private Partnership Procurem ent Process (2007); Co mp ilation of a Public Sector Benchmark (2007) | http://www.ppp.gov.ie/keydocs/guidance/central/Value%20for%20Money%20Technical%20Note.doc

http://www.ppp.gov.ie/keydocs/guidance/central/PSB%20Guidelines%20Jan%2007.doc

|

Note: URLs last accessed on May 28, 2008.

The four components are summed and compared with the combined cost of the private bids and the cost of the public's retained risks, as shown in Figure 1.

Besides the previous quantitative analysis, qualitative factors could also be considered. The public agency must identify the objectives and desired project outcomes and translate these into the performance standards on which to base the payment mechanism. The qualitative analysis considers whether the long-term contract can meet the objectives. It also considers important regulatory, public equity, efficiency, or accountability issues. Does the PPP improve on traditional delivery, financing, management, operations, or maintenance structures? Is the PPP procurement option feasible given current market conditions, the public agency's available resources (monetary and management experience), and the attractiveness of the proposed project? The GAO (2000b) found that both the states of Victoria and New South Wales, in Australia, have used qualitative analysis, along with quantitative analysis, to evaluate how the public interest is affected in a PPP.

Although VfM appears to be a useful tool to lead the PPP decision process, there are several criticisms of the VfM process. The most significant is that the PSC is a hypothetical case entirely dependent on the experience of the person(s) conducting the calculation. Inaccurate or erroneous estimates of cost and/or risk may seriously impair the PSC (Bloomfield 2006). Furthermore, the PSC is estimated using numerous assumptions and projections well into the future, adding a high degree of uncertainty (GAO 2000b).

FIGURE 1 PSC and value for money comparison. Source: Grimsey and Lewis (2005).