Enabling Statutes

Enabling statutes that grant an existing or new executive agency the authority to enter into one or more PPP agreements for transportation projects-and define the limits of that authority-are a necessary precursor to PPP implementation.97 These statutes set conditions that promote or prevent PPPs, guide development of state PPP programs, provide foundations for PPP contracts and affect the risks involved for each party.

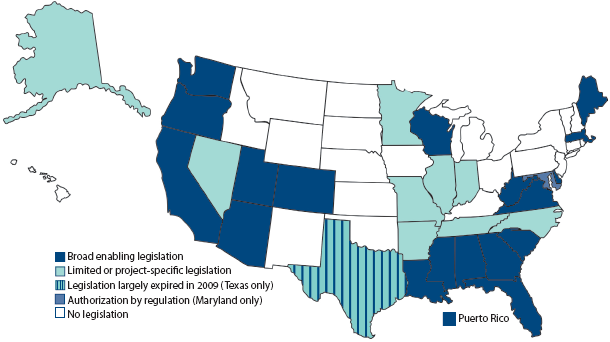

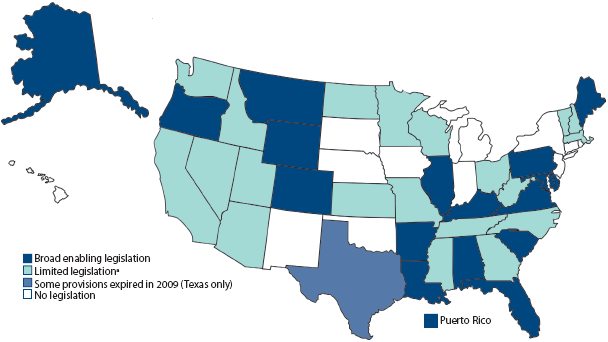

PPP legislation first was enacted more than 20 years ago in California (AB 680, 1989); a few years later, Virginia adopted its comprehensive Public-Private Transportation Act (1995). The number of states with PPP enabling statutes continues to grow. As of October 2010, 29 states and Puerto Rico had enacted laws authorizing PPPs for highway and bridge projects (see Appendix B and Figure 6)98 and 38 states and Puerto Rico had specifically authorized design-build approaches (see Appendix E and Figure 7).99 Model PPP and procurement legislation also has been developed.100

|

|

| Figure 7. States with Design-Build Enabling Legislation102 |

|

|

| aWithin this category are states that set restrictions on the cost of individual design-build projects (Massachusetts, Mississippi, Nevada, New Hampshire, Utah, Washington); limit the total cost or number of design-build contracts per year (Georgia, Idaho, Minnesota, North Carolina, Ohio, Tennessee, Vermont, West Virginia); authorize only a certain number of pilot or demonstration projects (California, Kansas, Mississippi, Missouri, North Dakota, Washington, West Virginia); include an end date or sunset provision (Arizona, California, North Dakota, Missouri, Utah, West Virginia); and/or strongly restrict the type of project (North Dakota, Wisconsin). |

States with PPP legislation seem to have reached consensus on some issues, such as allowing for design-build projects and use of federal TIFIA credit assistance (see Glossary). They vary widely on others, however, such as the powers delegated to executive agencies, the types of projects authorized and the ongoing legislative role. One recent report suggests that the many variations in states' PPP legislation reflect their philosophical orientation toward PPPs: aggressive (e.g. Indiana and Virginia), positive but cautious (e.g., Arkansas and Minnesota), and wary (e.g., Missouri and Tennessee).103

One area where states differ is whether they have provided enabling legislation on a project-by-project basis or have authorized ongoing PPP programs. As of October 2010, Alaska, Illinois, Indiana, North Carolina and Tennessee limited PPPs to selected "pilot" or "demonstration" projects.104 This approach allows a state to carefully consider the details of each project and gain experience with PPPs before committing to a larger program. Pilot projects also may show a lack of commitment to the PPP approach, however, which could dissuade bidders from investing substantially in the initial projects.105 If more than one project is anticipated, project-by-project legislation also can be time- and cost-intensive for both the public and private sectors; standardization of PPP procedures can streamline the process.106

In general, PPP statutes address key issues related to project selection and approval; the proposal review process; funding requirements and restrictions; procurement and project management; and toll management (Table 3). Specific key legislative provisions within these categories can include authorization to mix public and private funding; bidding procedures; a process for awarding contracts based on best value or other factors, not just low price; unsolicited proposals; tax provisions; authority to collect tolls or fares; bonding and debt; transparency and public participation; and contract provisions such as term lengths or noncompete clauses. Other important provisions can include designation or creation of a lead executive agency; structure and use of any proceeds; eminent domain; dispute resolution; reporting and review requirements; and cost-benefit or other analyses. (For more details about enabling statutes and their key provisions, see Appendices B and D.)