Legislative Approval

After legislation is passed, it generally is the responsibility of the authorized executive agency-such as a state or local transportation agency-to implement a PPP program and/or specific projects within the established statutory guidelines. Certain provisions, however, have created a more active, ongoing role for the state legislature by requiring its approval for some or all PPP projects.

Table 3. Examples of Provisions in State PPP Legislation by Category107 | |

Project Selection and Approval | Proposal Review Process |

• Allows for solicited and unsolicited proposals • Limits number of projects • Restricts geographic location • Restricts mode of transportation • Permits the conversion of existing or partially constructed roads to tollways • Requires prior legislative approval • Subjects approved PPPs to local veto • Restricts PPP authority to state agencies • Allows design-build • Allows HOT lane projects | • Allows public agency to hire own technical and legal consultants • Permits payments to unsuccessful bidders for work product in proposals • Allows public entity to charge application fees to offset proposal review costs • Allows adequate time for preparation, submission and evaluation of competitive proposals • Requires time for public review • Specifies evaluation criteria • Specifies proposal review structure and participants • Protects confidentiality of proposals and related negotiations |

Funding Requirements and Restrictions | Procurement and Project Management |

• Allows use of state and federal funds for PPP projects • Allows combination of local/state/federal and private funds on a PPP project • Allows use of TIFIA credit assistance for PPP projects • Prevents transfer of PPP revenues to general fund or for other unrelated uses • Allows public sector to issue toll revenue bonds or notes • Allows public sector to form nonprofits and lets them issue debt on behalf of a public agency | • Provides for multiple types of procurement, including design-build, competitive RFQ and RFPs, best bid rather than low bid, etc. • Exempts PPPs from state procurement laws • Allows outsourcing of operations and management • Requires public entities to maintain comparable non-toll routes • Addresses noncompete clauses • Allows long-term leases or franchises |

Toll Management |

|

• Determines who has rate-setting authority • Sets how and under which circumstances rates can be changed • Requires removal of tolls after debt is repaid | |

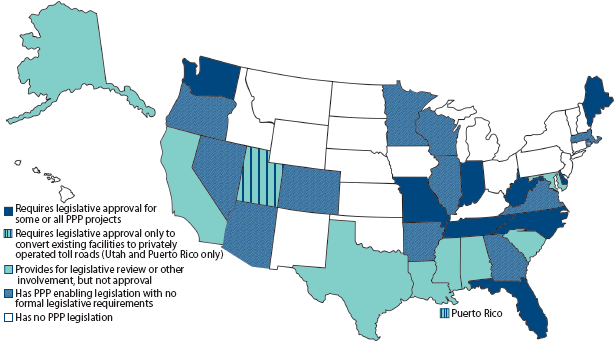

As of October 2010, Delaware, Florida, Indiana, Maine, Missouri, North Carolina, Tennessee, Washington and West Virginia required that at least some individual PPP projects be approved by the state legislature (see Appendix B and Figure 8). Of those, North Carolina required approval only for PPPs other than the five pilot projects listed in its statute, and Washington only for those PPP projects financed by tolls or other equivalent funding sources. In addition, Utah and Puerto Rico required legislative approval for converting existing facilities to privately operated toll roads. As another approach, at least eight states statutorily provided for some kind of legislative review but not approval of PPP projects.

|

Legislative approval provisions are controversial. On the one hand, they allow elected officials to review and be held accountable for individual PPP projects. Proponents argue this better protects the public interest, especially in large concession deals.109 Such requirements also add uncertainty to the process, however, and thus can discourage private investment. Private firms may be reluctant to develop costly project proposals if there is a risk that approval will not be given and negotiations will not close, even though a project has been selected and approved by the executive agency.110 This may be especially true for states that require legislative approval relatively late in the negotiation and contracting process (e.g., Florida for some projects, North Carolina and West Virginia) compared to Indiana, where the legislature must approve a request for proposals for a PPP project (see Appendix B).111

Legislatively Approved Transportation PPPs in the United States Legislative approval requirements in PPP enabling statutes are controversial (see pages 16 to 19). Proponents argue that they ensure accountability and protect the public interest,a while critics assert that they strongly discourage private investment by introducing political risk-especially where approval is required late in the procurement process. For example, the Reason Foundation has claimed that "in those states whose PPP enabling acts required legislative approval of negotiated deals [emphasis added], no such deals were ever proposed."b This raises the question of which, if any, PPP projects have moved forward under such legislative approval requirements- and at what stage they were approved, given the diversity of state approaches to this issue. Of the nine states that have any legislative approval requirements in their current PPP enabling statutes-plus California from 2005 to 2009-Florida and Indiana were found to have projects that were so approved. Indiana alone had a project approved after negotiations; the state's PPP statutes now require a different process. | ||

Florida law requires any PPP to undergo a form of legislative approval early in project development, "as evidenced by approval of the project in the department's work program" in the appropriations process. Further legislative approval is required to lease an existing toll facility, for a contract term of more than 75 years, or for a turnpike project. Florida has a vigorous PPP program, with seven current projects worth more than $3.7 billion and another in active procurement, but none so far has required approval beyond inclusion in the work program. |

| |

| Indiana's only current PPP project is the 75-year lease of the Indiana Toll Road, which was authorized in 2006 by what was effectively project-specific legislation-in the absence of any other enabling statute and after the final bidder had already been selected.c But two years later, that same approach-embarking on a PPP deal before having enabling legislation in place-contributed to the failed attempt to lease the Pennsylvania Turnpike. Former executive director of the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission, John Durbin, later said, "There will not be another consortium that will proceed in any state where they have to put their bids in first and then gain legislative approval to lease the asset."d The 2006 Indiana law does require legislative approval for all subsequent PPP projects, but earlier in the process. Certain actions-including issuing a request for proposals-are prohibited unless a statute is enacted to authorize them. Legislation was thus passed in 2010 to allow the proposed Illiana Expressway and other projects to move forward. | |

See Appendices B and G for more about these PPP enabling statutes and projects. a See Baxandall et al., Private Roads, 31. b Robert Poole, No Toll Czar: States, Not Feds, Should Protect the Public Interest in Public-Private Partnership Deals (Los Angeles, Calif.: Reason Foundation, Oct. 26, 2009), http://reason.org/blog/show/no-toll-czar-states-not-feds-s; see also Robert Poole, "Finally, California Gets PPP Legislation," Surface Transportation Innovations 65 (March 6, 2009), http://reason.org/news/printer/surface-transportation-innovat-64#feature6. c See NCSL Foundation for State Legislatures, NCSL Foundation Partnership: Public-Private Partnerships (P3s or PPPs) for Transportation Meeting Summary, July 20, 2009 (Denver, Colo.: NCSL, 2009), 22-23, http://www.ncsl.org/documents/transportation/Summit09P3mtgsum.pdf. d The Pew Center on the States, Driven by Dollars, 18. | ||

Opponents of legislative approval provisions generally advise that legislatures instead craft strong enabling legislation that carefully addresses key policy issues.112 Virginia, for example, established a PPP program based on comprehensive legislation that includes a public review process but not legislative approval. Another policy option is to statutorily provide the legislature with structured involvement other than project approval-for example, through opportunities for legislative review and comment or regular reports to the legislature on PPP activities. As of October 2010, eight states used this approach (Figure 8).

The United States has a distinctive separation of powers among its branches of government, and striking an appropriate balance between legislative and executive roles in the PPP process is both critical and diffcult.113 Legislators will want to consider this and many other issues as they approach the complex task of creating a meaningful policy framework for PPPs-some of which could endure for generations.