Principle 7: Support comprehensive project analyses

Before pursuing a PPP, it should be shown to be a better option than traditional project delivery.

| Many analysts counsel that the decision to pursue a PPP should be supported by a comprehensive project analysis- conducted as early as possible-showing that, over the duration of the contract, a PPP is truly a better option for the state than traditional project delivery.182 In 2008, the Government Accountability Office advised using a rigorous, up-front analysis to better secure the potential benefits of highway PPPs and warned that a failure to do so could lead to overlooking aspects of protecting the public interest.183 Legislators and executive agencies can support the use of these analyses, which inform project development, selection, approval and procurement. | •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• Thoughts from the NCSL Partners Project… On Building the Business Case Representative Terri Austin •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• |

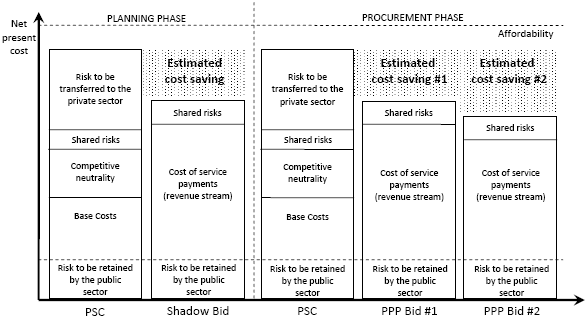

Value for money (VfM) is one analytical tool that has emerged as global best practice, primarily for greenfield projects; other financial tests are available for brownfield concessions.184 In general, VfM evaluates total project costs and benefits. VfM often incorporates a Public Sector Comparator (PSC) that estimates life-cycle costs-including operations, maintenance and improvements-for public project delivery. Using a PSC, a VfM analysis can ask whether a PPP offers better value for money in comparison to traditional project delivery, and can offer a comparison among PPP bids (Figure 9). A PSC also sets a threshold for private firms to meet or exceed.185

| Figure 9. Value for Money (VfM) Analysis Using a Public Sector Comparator (PSC)186 |

|

|

| Base costs are the actual costs (before risk) to the public sector including design, construction, operations, maintenance and asset rehabilitation. Competitive neutrality is included to remove the inherent competitive advantages (e.g., tax exemptions) or disadvantages (e.g., economies of scale) of a public agency compared to the private sector. |

VfM is used in Australia, the United Kingdom, British Columbia and others (see Table 5 for guidance documents); the UK and British Columbia use PSC for all potential PPPs. British Columbia has reportedly used traditional project delivery in many cases where VfM analysis showed the PPP approach did not offer enough value for money.187

| Table 5. Guides to Public Sector Comparator (PSC) and Value for Money (VfM) Analyses188 | |||

| Source | Country | Document | Web Site |

| Central PPP Unit | Ireland | Technical Note: Compilation of a Public Sector Benchmark for a Public Private Partnership Project (2007) | http://www.ppp.gov.ie/key-documents/ guidance/central-guidance/psb-guidelines-jan-07.doc/ |

| Technical Note: Value for Money in the PPP Procurement Process (2007) | http://www.ppp.gov.ie/key-documents/ guidance/central-guidance/value-for-money-technical-note.doc/ | ||

| HM Treasury | United Kingdom | Value for Money Assessment Guidance (2006); Value for Money Quantitative Assessment User Guide (2007) | |

| Canada | Methodology for Quantitative Procurement Options Analysis Discussion Paper (2010) | ||

| Partnerships Victoria | Australia | Public Sector Comparator (2001); Public Sector Comparator Supplementary Technical Note (2003) | |

Some governments also incorporate qualitative public interest tests and criteria for PPP project evaluation. For example, the Australian states of New South Wales and Victoria evaluate aspects of public interest-such as public access, effectiveness in meeting government objectives, accountability and transparency-before entering into PPPs.189 The United Kingdom complements quantitative tests with qualitative tests and uses both at various stages of the PPP process.190

The recent National Cooperative Highway Research Program report on public-sector decision making advises, "[The proper] development and use of valuation tools is potentially one of the most important means of helping the public and elected officials better understand the benefits, costs, risks and rewards of PPPs."191 In the United States, however, use of systematic processes and tools has been limited. Florida, Oregon and Virginia have reported using VfM; Oregon, Texas and Virginia have used forms of PSC.192 Texas has used so-called "shadow bids" to estimate costs for public project delivery for comparison with PPP proposals.193 As of 2007, Texas also required a "market valuation" analysis for new toll roads, which the 2008 Texas Legislative Study Committee advised be replaced by PSC.194

Legislators can set guidelines for project analyses in PPP legislation. Florida, Maryland, Washington and Puerto Rico statutes, for example, require a cost-benefit or other analysis during PPP project development or procurement.195 Puerto Rico requires its Public-Private Partnerships Authority to conduct desirability and convenience studies for proposed PPP projects. These can include a PSC-like comparative analysis of the cost-benefit of public project delivery versus a PPP approach, including the effect on public finances. Executive agencies can address analysis requirements in PPP program regulations and are generally responsible for implementing them. Legislators and executive agencies both can help provide adequate funding and build agency capacity to support effective analyses.196

Although VfM and other methods are useful, none is perfect. For example, PSC has been critiqued for using numerous assumptions as well as projections far into the future.197 These tools also continue to evolve. The United Kingdom, British Columbia and New South Wales have recently adjusted their analyses.198 Meanwhile, standards vary by country for calculating VfM or PSC199 and, in practice, some significant cost factors-such as depreciation of equipment and employee benefits-have been included in some analyses but omitted in others.200 Care should be taken when selecting, using and interpreting the results of analytical methods to support and inform PPP decisions; these tools can aid, but not replace, decision making.