4.4. Understanding the importance of Risk Transfer

One of the most significant advantages of PPPs is the ability to transfer of risk from the state to the private participants. These risks may be grouped into two basic categories: operating risks and financial risks.95

Most PPP contracts, including the one CDA in Texas to date, require the private company to assume the risk of unexpected obstacles in the construction process, ranging from poor soil conditions to the discovery of endangered species to the doubling of concrete prices.

Historically, the greatest risk in a toll project is that actual traffic - and thus toll revenue - will fall well short of projections.96 This has, in fact, been quite common throughout the developed world.

A recent study of 23 U.S. toll projects (nearly all done by public sector agencies) determined that most did not meet their initial traffic and revenue (T&R) projections.

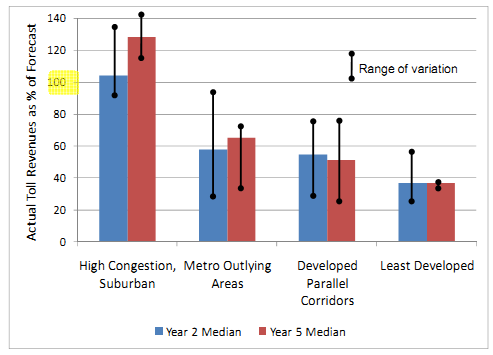

ACTUAL TOLL REVENUES AS A PERCENTAGE OF FORECAST REVENUES97

The NCHRP study divided these 23 projects into the four categories shown above, and found that performance versus projections after years 2 and 5 varied significantly depending on the general location of the project (large variations existed within particular categories as well).

"High Congestion Suburban" toll roads (n=3) - a category that included the NTTA's George Bush Turnpike - were the most reliable performers.98 "Metro Outlying Areas" (n=7)99 and "Developed Parallel Corridors" (n=5) - a category that contained HCTRA's Sam Houston and Hardy toll roads - had a median performance of around 50 percent.100

Bringing up the rear were those toll roads in the "Least Developed Areas" (n=8), such as Virginia's Pocahontas Parkway and Dulles Greenway.101

T&R counts for overseas PPPs have also fallen well short of projections. For instance, Sydney, Australia's Cross-City Tunnel slid into insolvency as traffic topped out at 35,000 vehicles per day (versus 90,000 forecast), and the low volume in the Lane Cove Tunnel to the city's northwest has already led the LCT's primary investors to write off most of their investment - though both projects were sorely needed from a congestion relief standpoint.

The fact that T&R projections have proven overly optimistic leads to the questions of 1) why are they high; and 2) what are the consequences of T&R forecasting errors? Addressing the first question, the literature offers several possibilities:

• Toll roads in many cases are relatively new to a region, and the forecasters lack experience (projections, therefore, should improve over time as personnel become more skilled);

• Initial T&R projections are driven by financing considerations, rather than vice versa.

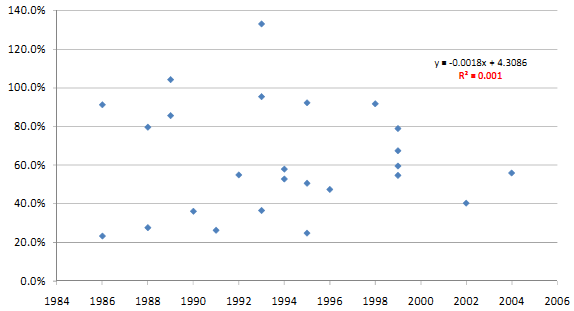

A statistical review of the 23 projects does not show any correlation between time and forecasting accuracy.

YEAR 2 TOLL REVENUES VS FORECASTS102

One explanation for the lack of apparent improvement in T&R projections is that the projects in question were scattered across the United States. Thus, rather than one group of forecasters gaining valuable experience and improving over time, each particular road involved what were essentially rookie forecasters starting from scratch. This speaks for the establishment of an interstate and/or federal compilation of best practices. The Australian federal government has recently taken such a step, combining the already extensive work done by the states of Victoria and New South Wales.

A more troubling issue, though, is the possibility that financing considerations are driving the traffic projections rather than the other way around. One of the three major firms involved in the traffic forecasting process has admitted that his consultants are under great pressure to supply numbers that sell bonds.103 The scandals surrounding appraisals in the current mortgage market - "made as instructed" valuations performed by appraisers who relied on a few local financial institutions for the bulk of their revenues - have amply demonstrated the ever-present temptation for appraisers to provide the numbers that their clients desire, even if such numbers run contrary to their own professional judgment.

Given the prevalence of T&R forecasting errors, the question becomes how to protect the state's interests when road projections go wrong - whether by design or mistake. The Committee examined a number of PPP toll projects, both in the United States and abroad, where the road fell into financial difficulty shortly after opening for traffic.104

In one respect, what the Committee found was encouraging - from the standpoint of the state. The transfer of risk worked exactly as it should have. The private investors lost heavily and the state, in the end, received a high quality asset at a discounted price. Even a critic of PPPs admitted that this was the norm: "no matter what happens, [the state] will get a road, and that's how they're selling [toll road bonds] across the United States."105

Three examples follow:

____________________________________________________________________________________________

95 For this purpose, Operating Risk includes all phases of the project's operations: site, design, construction, commissioning, operation and maintenance risk. Financial Risk includes changes in interest rates, investor perception of particular asset classes, market demand for securities, and tax rates. Financial risk also includes the failure of a project to meet projected traffic and revenue provisions.

In addition the state bears Sponsor risk - the risk that the private company proves to be unable, financially or technically, to complete the project - as well as Termination Risk - that the value of the asset at the contract's end proves less than expected or that the asset is in worse condition than the contract called for.

For a thorough analysis of the major PPP risks, see Working with Government: Guidelines for Privately Financed Projects, Appendix 3, by the Government of New South Wales (Australia), December 2006.

96 Our research has not found any examples in the developed world where a private developer became insolvent before completing the project.

97 National Cooperative Highway Research Program, Synthesis 364, Transportation Research Board of the National Academies.

98 Others in the 'High Congestion, Surburban' were the GA400 (Atlanta) and the Illinois North-South Tollway (Chicago).

99 Including the Foothill Expressway (Orange Co., CA); Seminole Expressway (Orlando, FL); Veterans Expressway (Tampa); Florida Turnpike Enterprise Polk (Lakeland); Central Florida Greenway (Orlando); Creek Turnpike

(Tulsa, OK); John Kilpatrick Turnpike (Oklahoma City).

100 Others in the Developed Parallel category included Orange County, CA's Foothill Eastern and San Joaquin Hills tollways, as well as the Garcon Point Bridge (Pensacola, FL)

101 Others included the E-470 (Denver); Sawgrass Expressway (Fort Lauderdale, FL), Central Florida Greenway (Orlando), Osceola Parkway (Osceola County, FL) and the Greenville Connector (Greenville, SC)

102 Source: National Cooperative Highway Research Program, Synthesis 364, Transportation Research Board of the National Academies.

103 Plunkett, Chad, "Roads to Riches," Denver Post, October 25, 2006.

104 The Committee was unable to locate any statistics comparing the accuracy of various forecasting firms.

105 Plunkett, Chad, "Roads to Riches," Denver Post, October 25, 2006.