6.3. Primacy

One of the more controversial aspects of PPPs revolves around the issue of who has the right to build a toll project in a particular region.

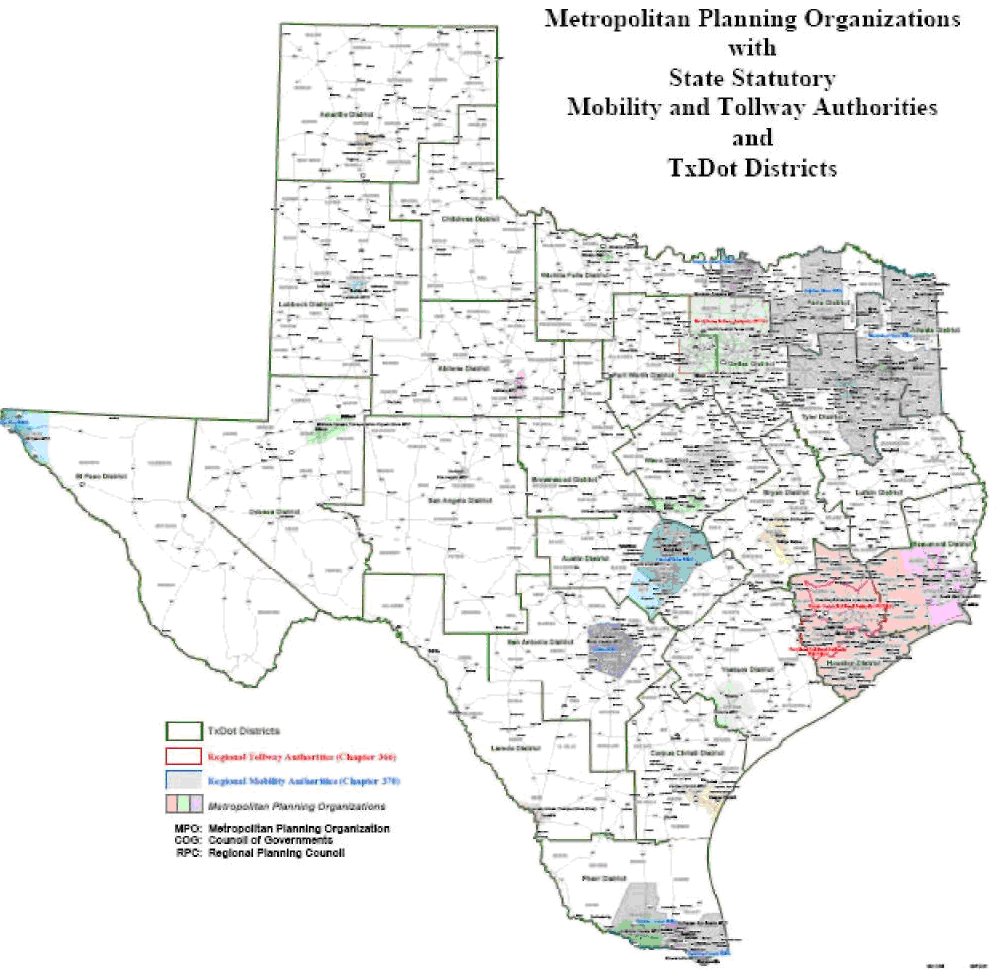

Current federal law requires there to be a Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) for each urbanized area with a population of more than 50,000, in order to carry out the transportation planning process. At the present time, Texas has 25 MPOs.152

MPOs, however, do not actually build the highways. That responsibility lies with either TxDOT or a local "Toll Project Entity" (TPE). At the present time, Texas authorizes three types of TPEs: Regional Mobility Authorities,153 a Regional Tollway Authority,154 and county based authorities (i.e, HCTRA). Each of these has similar powers within their respective regions.

Under SB792, a local TPE has the first option to develop a toll project. This option lasts for six months after the date that a market valuation155 of the project is mutually approved by TxDOT and the TPE.156 Once the TPE chooses to exercise the option, it must enter into a contract for the financing, construction and operation of the project within two years after clearing environmental and legal hurdles.157

There is broad agreement that the current process is unsatisfactory, but no consensus has emerged as to what mechanism should replace it.

Witnesses before the Committee have set forth varying proposals. One would create a flow chart with the following priorities, in order:

1. The local TPE develops the project as a publicly operated project

2. TxDOT develops the project as a publicly operated project

3. The local TPE develops the project as a PPP

4. TxDOT develops the project as a PPP.

Under this proposal, each entity would have a certain number of days to exercise its option as well as a two-year time window (as in current law) to sign the project contract.

This proposal, however, seems geared more to the choice of whether a project will be developed as a PPP or as a public project, rather than settling the more fundamental issue of the limits of regional control.

Specifically, what is the extent of the power that a local TPE has over the projects in its region, and what rights do dissenting members of that region have to develop a project that those in charge of the regional TPE have not deemed a priority? This is especially significant in regions where the MPO encompasses a much broader geographic area than the regional TPE, or in regions where various sections within the region have a history of acrimony and conflict.

Our review of other jurisdictions indicates that Texas is somewhat unique in the relationships between the state DOT and local toll road entities, as well as the variety and proliferation of these entities.

Various transportation conferences and regional gatherings have revealed proposals to create even more types of transportation funding entities in the upcoming 2009 legislative session. The subjects of overlapping jurisdictions and conflict between entities remain a serious concern.

MPOs, Toll Project Entities and TxDOT Districts158

Many jurisdictions overseas avoid the issue of inter-departmental conflict by consolidating the responsibilities for handling toll projects within a single department or public corporation. For instance, in Australia, contracts for toll projects in the cities of Sydney and Melbourne are awarded by the states of New South Wales and Victoria, respectively.159 Neither metropolitan region contains the equivalent of a regional tolling authority, though one distinction between Australian states and Texas is that very high concentrations of the Australian states' populations live in a single metropolitan area, blurring the division between state and city governments. 160

In Canada, British Columbia has created a public corporation, Partnerships British Columbia, which is wholly owned by the Province and reports to its only shareholder, the Minister of Finance.

Some of our sister states within the U.S. have multiple entities responsible for toll projects, but these have - at least to date - avoided the jurisdictional conflicts observed in Texas.

In Virginia, state law mandates the selection of a "coordinating responsible public entity" for each project that requires the approval of more than one public entity,161 and only after such a determination is made can the project proceed. The only Virginia entity similar to a Texas TPE is the Richmond Metropolitan Authority, which operates three Richmond area toll roads (along with parking decks and a baseball stadium). According to a committee witness, VDOT and the RMA have worked well together in a cooperative relationship for the past 30 years.162

Florida, like Texas, has a number of regional authorities in addition to FDOT's tolling subsidiary, the Florida Turnpike Enterprise.163 Each of the regional expressway authorities was created by the Florida legislature and the state's governor appoints some of their board members. To date, Florida has no state law on primacy, but concessions have been introduced without jurisdictional conflicts.164

Focusing on the fundamental issue of the relationship between the various entities also serves to concentrate attention on the critical issue of highway finance governance, as the level of control is tied to the ability of regional TPEs to manage the process effectively. Are the interests within the region aligned in a manner that will lead to a positive result for the public, regardless of whether the region's toll projects are public or private? Do the regional TPE managers have the skills and expertise to manage road contractors (if the TPE develops its own projects) or to negotiate complex contracts with private parties in the case of concession agreements?

Texas is not alone in confronting this issue. For instance, a recent report on PPPs in Spain concluded that "as PPP activity decentralizes and accelerates at regional and local levels of government, authorities entering into complex negotiations may be doing so without the tools that are necessary to guarantee that the projects deliver value for money … [emphasis added]. The risk inherent in this approach is either renegotiation at higher prices in the future, lower quality services or the [non]viability of projects over the medium and longer term."165

Finally, the issue of management raises two other primacy-related concerns: 1) will potential conflicts between entities lead to higher costs and delays inherent in a piecemeal versus a system approach; and 2) could a local entity get in over its head and leave the state's taxpayers to pick up the pieces after the unraveling of poor financial decisions?

The issue of system finance, like the subject of buybacks, is inextricably linked to decisions regarding cross-subsidization and the ability of a region to utilize the few highly profitable roads available to it to fund additional transportation infrastructure. Taking SH121 as an example, the NTTA argued that allowing a private concessionaire to take what is likely to be one of the highest revenue generating roads in the DFW Metroplex out of the system would lessen NTTA's own ability to sell bonds for other planned roads with more uncertain traffic and revenue forecasts (though the private party argued that its up-front concession payment would allow TxDOT and the benefiting region to build many of those roads if it so chose).

At what point are the benefits of a true competition for the rights to develop highly profitable roads likely to be negated by the inefficiencies of an individual project approach, rather than a system finance approach?

And, if a system approach proves to be the most beneficial, on balance, should the state seek to restrict "excessive" local primacy - such as the reported efforts by Collin County to set up a Collin County Toll Road Authority, given this new authority would exist entirely within the existing boundaries of the well established NTTA?

Finally, beyond the technical and transactional skills required of any successful entity involved in project management, the local TPE must also have the financial wherewithal to complete the tasks it has assigned itself, and with a reasonable margin of safety for untoward events, whether in the construction process or the financial markets.

Without careful attention, it is conceivable that an emphasis on local primacy could have the detrimental effect of either leaving certain projects un-done, or in a worst case, exposing the entire state's taxpayers to a regional Toll Project Entity's financial choices that turn out, in hindsight, to have been ill-advised.

The recent agreement by TxDOT to backstop the SH161 project sets a somewhat troubling precedent. Though the transaction is intended as a one-off proactive solution to get a specific project moving in the face of a global economic crisis and market illiquidity, we are concerned that it could be the first step on a slippery slope of others seeking the same Fund 6 guarantees for local projects - a situation all the more ironic because Texas is considering additional toll road financing precisely because Fund 6 is running short of cash.

The SH161 backstop will require TxDOT to make up only the shortfalls between actual and expected toll revenues. If for instance, forecast revenues are $60 million while actual revenues are $50 million, Fund 6 will only pay $10 million for that particular year. The agreement also specifies that "it is TxDOT's objective that it be relieved of its toll equity loan payment obligations as soon as possible."166

However, we also noted in previous sections that many toll roads fall well short of their traffic and revenue projections, and observe that the current financial crisis is replete with examples of guarantors suddenly being called upon to repay obligations for which their sophisticated financial models projected an almost infinitesimal probability of default.

Several of the personnel involved in the drafting of this report recently attended a transportation conference where one of the presenting bankers enthusiastically described the SH161 transaction and urged the attendees to obtain a similar deal for their own projects.

Finally, local primacy raises the question of whether an overextended and financially unstable local TPE would ever be allowed to truly default in the manner of a private concessionaire. As we have witnessed with the travails of Fannie Mae and other government sponsored entities, implicit governmental guarantees have a way of becoming explicit and creating significant moral hazard.

______________________________________________________________________

152 These are Abilene, Amarillo, Brownsville, Bryan-College Station, Capital Area (Austin), El Paso, Harlingen-San Benito, Hidalgo County, Houston-Galveston, Jefferson-Orange-Hardin Regional, Kileen-Temple, Laredo, Longview, Lubbock, Midland-Odessa, North Central Texas (DFW), San Angelo, San Antonio-Bexar County, Sherman-Denison, Texarkana, Tyler, Victoria, Waco, Wichita Falls. Source: www.planning.dot.gov/mpos1.asp.

153 Texas currently has eight RMAs: Alamo RMA (San Antonio), Cameron County RMA, Camino Real RMA (El Paso), Central Texas RMA (Austin), Grayson County RMA, Northeast Texas RMA (Tyler), Hidalgo County RMA, and Sulphur River RMA (Paris). Source: TxDOT.

154 Currently, the NTTA is the only regional tollway authority in the state.

155 This report will address the subjects of market valuation in a separate section.

156 SB792, §228.0111(e) and (f) require that a market valuation be obtained once 1) TxDOT or a local TPE determines that a particular project should be developed as a toll project; and 2) TxDOT and the TPE have agreed on terms and conditions for the project, including the initial toll rate and escalation methodology. After this, TxDOT and the TPE are to mutually agree upon which entity shall conduct the valuation. Once the valuing entity issues a final draft valuation, TxDOT and the TPE have 90 days to approve the valuation or negotiate and alternative. If TxDOT and the TPE cannot agree, then the draft valuation is deemed final. If TxDOT and the TPE cannot agree on terms and conditions, or upon which entity is to conduct the market valuation, then the project cannot be developed as a toll project.

157 Some variations exist depending on whether the TPE is a county, a regional tolling authority or an RMA. Also, SB 792 excluded certain existing or planned toll projects from these general provisions.

158 Source: Texas Legislative Council

159 Partnerships Victoria, set up to manage PPPs in the state, is part of the Commercial Division of the Department of Treasury and Finance.

160 For example, approximately two-thirds of NSW's population lives in metropolitan Sydney, while nearly 75 percent of Victoria's population lives in the greater Melbourne area.

161 Virginia Code § 56-566.2. See Virginia Code §56-556 et seq (the Public-Private Transportation Act of 1995)

authorizes both unsolicited bids by private parties and requests for proposals by responsible public entities.

162 Barbara Reese, VDOT .

163 These include the Miami-Dade Expressway Authority, the Tampa-Hillsborough County Expressway Authority, and the Orlando/Orange County Expressway Authority.

164 Source: Lowell Clary, formerly of FDOT.

165 Allard, G., Trabant, A., "Public-Private Partnerships In Spain: Lessons And Opportunities," International Business & Economics Research Journal, Vol. 2, No. 7, February 2008.

166 Source: Final Term Sheet for TxDOT Toll Equity Loan for SH161 Project, NTTA Project Delivery and Disposition of Southwest Parkway and Chisholm Trail, TxDOT Final 10/14/08.