Pursue PPPs For The Right Objectives: Lower Lifecycle Costs and Better Maintenance

In the United States generally and in New York specifically, PPPs should be pursued for two related purposes: lowering the lifecycle costs of an asset and achieving better standards of maintenance than under direct public management. The ability of PPPs to lower lifecycle costs is rooted in their competitive award process and their incentives for encouraging designs that reduce operating and maintenance costs; delivering major construction work in a more timely fashion; and keeping facilities in a state of good repair throughout their lifecycles. The potential for higher maintenance standards is rooted in the tendency for assets to be neglected in the later stage of their life under direct public management.

The neglected condition of American infrastructure has been well documented. The evidence is not just in tragic events such as the 2007 bridge collapse in Minnesota, but also in multiple expert studies. The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) estimates that $1.6 trillion in investment is necessary in the next five years to bring the nation's infrastructure to a good condition. ASCE surveyed 15 categories of infrastructure, with nine categories- including roads, schools and energy- receiving a "D" grade. The highest grade awarded was a "C+" for solid waste facilities, and the worst grade, "D-," went to drinking water systems, navigable waterways and wastewater systems.16

National studies focused on transportation and water systems point to the same troubling conditions. For water infrastructure, a 2002 report by the Congressional Budget Office estimated between $26.9 and $42.7 billion in 2001 dollars is necessary for water and wastewater infrastructure systems annually for the period from 2000-2019.17 In addition, ASCE reports that the number of unsafe dams is increasing at a rate faster than the number being repaired, with $10.1 billion needed over 12 years to address all critical dams.18

For transportation infrastructure, the National Surface Transportation Commission estimated in its December 2007 report that at least $220 billion- about $135 billion more than currently invested- is needed annually through 2035 to maintain and improve all modes of surface transportation: highways, mass transit, freight and passenger rail.19 Currently, 27 percent of the nation's bridges are deficient or obsolete; 15 percent of road pavements are rated "not acceptable;" 51 percent of urban rail stations are substandard; and the average condition of rail vehicles and urban bus fleets is no greater than "fair."20 Increased investments are needed to addresses the existing deterioration and perform improvements necessitated by increased population and use of the systems.

Surprisingly little evidence exists that PPPs successfully address the problems of high cost and poor maintenance. PPPs have not been carefully evaluated based on these criteria, but the limited evidence from a series of evaluations in the United Kingdom and Australia indicate that they perform as expected in promoting these goals.

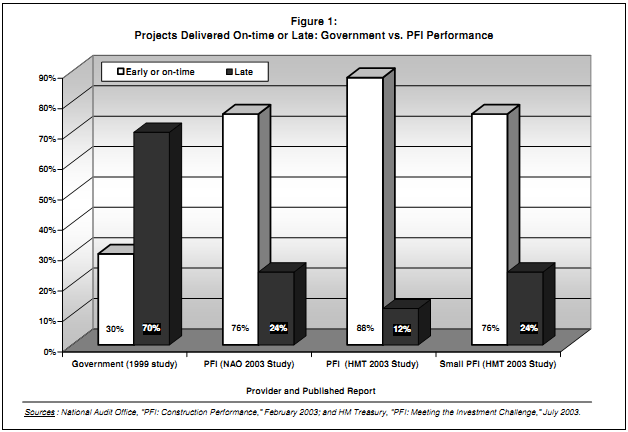

Studies conducted in the United Kingdom have systematically evaluated PPPs. Three studies address the issue of delivering projects on time and on budget. A 1999 study by the U.K. National Audit Office (NAO) examined the experience with 66 projects completed using traditional government procurement practices; this provided a baseline for comparison with 37 projects using PFI contracts examined in a 2003 NAO study.21 Another 2003 study by Her Majesty's Treasury (HMT) examined the experience with 61 larger PFI projects and 35 smaller PFI projects with a contract value less than £20 million.22

The results confirm favorable performance under PPPs. (See Figure 1.) While 70 percent of the conventionally procured projects were delivered late, only 24 percent of PFI projects surveyed in the NAO study were late by comparison. This finding was supported by the HMT study, which reported that only 12 percent of large projects and 24 percent of smaller projects were delivered late.

The studies also considered whether the projects were delivered on or over budget. Because the private partner bears the risk for any over budget costs under the PPP model, data were not always available; therefore, the results are relevant only to the extent that they support or contradict the broader benefits of PPPs rather than direct savings to government. Nonetheless, the data show that PPPs are effective. While 73 percent of the conventionally procured projects were over budget, only 22 percent of PFIs in the 2003 NAO study and 17 percent of smaller PFIs in the 2003 HMT study were reported to exceed budget. (Data were not available for the larger projects in this study.)

Evidence from Australia substantiates these findings. A 2007 report commissioned by Infrastructure Partnerships Australia, a group with public and private sector participation that aims to promote best practices, examined 33 traditional projects and 21 PPP projects. The report demonstrated superior performance by PPPs in time and cost, with the benefits of PPPs increasing with the size and complexity of projects. The PPP projects examined were worth AU$4.9 billion, with net cost overruns of AU$57.6 million, or 1.2 percent; on the other hand, traditional projects, with a cost of AU$4.5 billion, suffered from net overruns of AU$673 million, close to 15 percent. Furthermore, PPPs were completed 3 percent ahead of schedule on average, compared to 24 percent late for traditional projects. The performance differential between traditional projects and PPPs was statistically significant in both cases.23

Part of the gains of PPPs over traditionally-procured projects results from the relatively minor contract changes during the construction period. A 2008 NAO study examined the nature of contract changes in 390 operational PFI projects in the U.K., and found that the vast majority (82 percent) of change requests had associated costs of less than £5,000.24 The cost of all contract changes in 2006 totaled about £180 million, 3.6 percent of the £5 billion in availability charges that year.25

It should be noted that the added cost of the changes is based on the total life cycle costs associated with the changes. For example, when a PPP for court building in the village of Worle required conversion of two rooms and some other renovations, the cost was calculated to include the initial cost of the work (£96,000), lifecycle costs (£56,000) and other fees (£48,000) and miscellaneous costs (£18,000), for a total of £218,000. In contrast, a similar conversion of a courthouse in Bridgewater via conventional procurement cost £117,000 - including initial construction cost of £100,560 and a contingency sum of £6,000. No funds were included for maintenance of facilities that should occur or for future replacement and repair that may be necessary; that is, no estimates for whole-life costs were provided.26

The complexity of calculating these lifecycle costs (and associated disputes between the partners) was sometimes a source of delay in implementing the changes. These complexities also meant that small changes could cause longer delays than would occur for similar changes in conventional procurement practices, although urgent changes would be processed without delay. Interestingly, many of the changes requested were considered during the negotiation of the deal, but were left out due to affordability concerns; however, undertaking work as a contract change, rather than at the outset of the project, typically made the work more costly. Larger changes, however, were generally in line (both time and cost wise) with conventionally procured work.27

The pattern of fewer contract changes for PFI projects can be attributed to better scoping and planning. A study commissioned by HMT compared planned against actual performance with respect to project procurement and delivery for 50 major public projects, both PFI and non-PFI. It found that PFI projects had less underestimation of project cost and delivery time and/or overestimation of benefits than for traditional projects. The key reasons were better project scoping, identification and management of risk, and due diligence performed during the procurement stage; in other words, PFI projects forced government to be more specific about its goals and committed to its requirements than was common for traditional projects.28 This was echoed by the 2003 NAO report, which acknowledged that specifications for PFI projects are worked out in greater detail in advance, with cost and time targets set later in the procurement process than under traditional methods.29 At the time, this process was quite lengthy: an average of 22 months.30

Less extensive evidence is available on the performance of PPPs in providing better maintenance standards. Because most PPPs are relatively new and because the projects have long lifecycles, no studies have been able to determine the long-term impacts on lifecycle costs. Instead, the limited available evidence offers some insight into adequacy of maintenance in the earlier stage of project operations. Specifically, a study in 2006 by HMT and Partnerships UK, a nonprofit organization, surveyed the contract managers of a sample of 105 projects, most of which were in their first five years of operation. The findings were favorable: 66 percent of projects surveyed were performing to a good or very good standard and another 30 percent were performing satisfactorily, for a total of 96 percent. Project managers pointed to day-to-day maintenance and hard facilities management as areas where they were especially pleased with the performance of private contractors. Furthermore, performance improved after the early years; projects operational for a greater duration of time received higher marks. In addition, among projects reporting problems, 82 percent also reported that the problem had been resolved within the time permitted in the contract. 31

Less systematic data from a few of the larger PPPs in the United Stares indicates they too have good records in asset maintenance. Private operators of JFK Terminal Four (T4), NYC street furniture, and the Indiana Toll Road (ITR) have all implemented technological innovations and are maintaining assets at a level as good as or better than previous owners. The ITR contract agreement specifies operating and maintenance standards affecting everything from temporary pothole repairs and standards for pavement smoothness and strength to landscaping and litter collection to preventative maintenance on bridge structures and emergency roadside repairs.32 It also lays out specific requirements for capital improvements, including the installation of electronic tolling, to total $4 billion over the life of the agreement, as well as conditions under which the consortium must initiate expansions.33

Cemusa's street furniture has been constructed from impact-resistant, vandalism-proof materials and must contractually be maintained at a high level, including the performance of preventive maintenance.34 JFKIAT's design, amenities, maintenance and technological innovations, such as common use ticketing counters, have earned T4 high marks for comfort, cleanliness and overall terminal performance from passengers surveyed by JD Powers & Associates.35

See also other operating and maintenance standards manuals available online at http://www.in.gov/ifa/2474.htm.

___________________________________________________________________________

16 American Society of Civil Engineers. "Infrastructure Report Card 2005." Accessed 15 July 2007, updated 2008, available online at http://www.asce.org/reportcard/2005/index.cfm.

17 Congressional Budget Office. "Future Investment in Drinking Water and Wastewater Systems." November 2002. Available online at http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/39xx/doc3983/11-18-WaterSystems.pdf

18 American Society of Civil Engineers. "Infrastructure Report Card 2005: Dams." Accessed 15 July 2007, updated 2008, available online at http://www.asce.org/reportcard/2005/page.cfm?id=23

19 Report of the National Surface Transportation Policy and Revenue Study Commission. December 2007. Volume II, Chapter Four, pp. 4-25.

20 Report of the National Surface Transportation Policy and Revenue Study Commission. December 2007. Volume II, Chapter Four, pp. 3-13.

21 U.K. National Audit Office. "PFI: Construction Performance." HC 371 Session 2002-2003. February 2003. Available online at http://www.nao.org.uk/publications/nao_reports/02-03/0203371.pdf.

22 See HM Treasury, "PFI: Meeting the Investment Challenge." July 2003. Available online at http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/media/F/7/PFI_604a.pdf.

23 The Allen Consulting Group. Performance of PPPs and Traditional Procurement in Australia. Report to Infrastructure Partnerships Australia. 30 November 2007.

24 Small projects with a value under £20 million and IT projects were excluded. Very large projects, such as the London Underground, were also excluded. See National Audit Office, "Making Changes in Operational PFI Projects." HC 205 Session 2007-2008. 17 January 2008.

25 National Audit Office. "Making Changes in Operational PFI Projects." HC 205 Session 2007-2008. 17 January 2008. Available online at http://www.nao.org.uk/publications/nao_reports/07-08/0708205.pdf.

26 National Audit Office. "Making Changes in Operational PFI Projects." HC 205 Session 2007-2008. 17 January 2008. Page 14.

27 National Audit Office. "Making Changes in Operational PFI Projects." HC 205 Session 2007-2008. 17 January 2008.

28 Mott MacDonald. "Review of large Public Procurement in the UK." Prepared for HM Treasury. July 2002.

29 National Audit Office. "PFI: Construction Performance." HC 371 Session 2002-2003. February 2003. Available online at http://www.nao.org.uk/publications/nao_reports/02-03/0203371.pdf.

30 HM Treasury. "PFI: Meeting the Investment Challenge." July 2003. Available online at http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/media/F/7/PFI_604a.pdf.

31 HM Treasury. "PFI: Strengthening long-term partnerships." March 2006. Available online at http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/media/7/F/bud06_pfi_618.pdf.

32 Indiana Finance Authority. "Concession and Lease Agreement for the Indiana Toll Road. Volume I of III: Maintenance Manual." Available online at http://www.in.gov/ifa/files/TRvolume_I.pdf.

33 Indiana Toll Road Concession Company. "ITRCC announces $250 million road expansion." Press Release, September 28, 2006. Available online at https://www.getizoom.com/aboutITR/PressRel_PDF/092806250_Expansion.pdf.

34 The City of New York. "Franchise Agreement between the City of New York and Cemusa, Inc. Coordinate Street Furniture Franchise."

35 JFKIAT. "Terminal 4 By the Numbers." Webpage accessed 25 September 2007.