Risk Allocation Process

In project financing, contracts create the underpinnings of the security for the project debt. As such, the agreement between the government and the prime contractor allocates key risks and forms the linchpin of the entire transaction. The prime contractor, in turn, has its team allocate the risks to the parties best equipped to manage and underwrite them. For example, the engineer, procurement, and construction subcontractor or "EPC contractor" will assume the responsibility for constructing the facility according to strict schedule, budget, and performance requirements. These commitments will be backed by penalties in the event that the EPC contractor fails in some way. The penalties typically take the form of liquidated damages and range from 10% to 100% of the contract value. In return, the contractor often receives bonuses for early completion and will earn higher margins on the work performed under this arrangement.

Ideally, project risks will be spread among the project participants in a way that optimizes the economics of the project. Generally, project risks should be allocated to the party best equipped to manage them. For example, change-in-law risk should be allocated to the government because it controls this risk element. Alternatively, commercial risks, such as construction and operations, should be allocated to the private contractor. For risks that are beyond the control of both the contractor and the government (e.g., force majeure events) it is usually more economical to allocate these risks to the government because it has greater capacity than the private insurance market to underwrite them. Although the government will negotiate with one contractor, the risk allocation process will involve other parties as the contractor spreads the risk among its team including the EPC contractor, the O&M contractor, technology and equipment suppliers, insurance providers, etc. As can be seen in Figure 1, the process of risk allocation involves assigning specific risks to specific parties with the objective of effecting an optimal allocation of risks that results in the least cost to the government.

| WHO TAKES? | ||||||||||

DEV | EPC | C & m | CUS | EQUP | TECH | INSUR | EQUITY | SUPPLIER | OFF-TAKE | EQUIP | |

1. Revenue Structure |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2. Technology Performance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. Construction |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Operations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

S. Site Conditions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

G. Feedstock (Waste Supply) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7. Permitting & Development |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

a. Comparative Economics & Price |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9. Inflation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10. Change-in-law |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11. UCC (Force Majeure) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12. Ownership Risk & Liability |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

• UCC= Uncontrollable Circumstances; C.I.L. = Change in Law

Figure 1. Project Risk Allocation

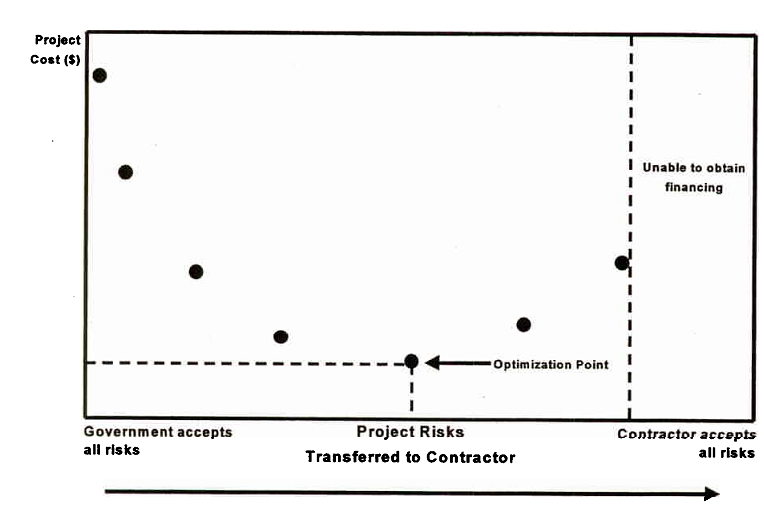

This optimization process recognizes that the costs of the project may increase as greater amounts of risks are placed on the contractor. As shown in Figure 2, shifting risk to the contractor can move the project to an optimization point where overall project costs are minimized. However, if too much risk is passed to the contractor, the contractor may not be able to obtain nonrecourse financing for the project. This constraint requires the government, the contractor, and the lenders to reach a balance of project risk assumption.

Figure 2. Optimization Curve

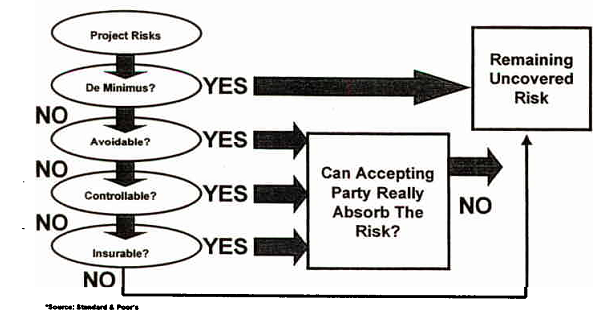

The risk allocation result directly affects the financial feasibility of the project. As depicted in Figure 3, the process used by lenders and credit analysts attempts to identify any risk that remains uncovered by the project participants. Lenders will analyze the project risks and will determine their magnitude and ability to be managed. In the event the "remaining uncovered risks" are significant or unmanageable to the parties in the transaction, the lenders will avoid the transaction.

Figure 3. Lender Risk Analysis

To mitigate the lender's concerns, the contractor may find alternative sources, such as additional equity or "mezzanine financing" (i.e., subordinated debt). Alternatively, the borrower will obtain commercially available insurance to cover specific risks or will guarantee a portion of the debt with its balance sheet. This will increase the comfort senior lenders will have in the timely repayment of principal and interest. However, it also will increase the cost of financing associated with project. To the extent risks remain unmitigated, they are risks that the lender is assuming. Although the lenders will be compensated for this added risk, there is a point at which they simply will not lend to the project (see Figure 2), rendering the project financially infeasible. Therefore, the challenge in structuring a project is to develop terms and conditions which result in a risk allocation that places risks under the control of the party best equipped to manage them. This, in turn, provides incentives that are well aligned with the programmatic mission behind the function being privatized.