Methods for Government Participation

Government participation in a specific transaction can include a broad range of options, but as a general rule, the method and magnitude of this participation should depend on the unique requirements of the project and should serve to enhance the project's ability to raise private financing. As the project's risk allocation between the government and the contractor forms the foundation on which other enhancements can build, it is first important to analyze methods for directly improving the project's financeability through alternative risk allocation structures. DOE contracts, for example, often involve the handling and treatment of mixed radioactive materials. The risks presented to the contractor are often unique and therefore raise concerns to lenders and investors because they have a difficult time in analyzing and quantifying the risks. For this reason, DOE often takes certain risks that the private sector cannot absorb (e.g., radiological risks under Price Anderson). In some cases, this process may involve clarifying the risk allocation to make it conform to the commercial models that are familiar to the financial community. This can be accomplished with special contract clauses that provide clarifications to or deviations from language contained in the Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR).

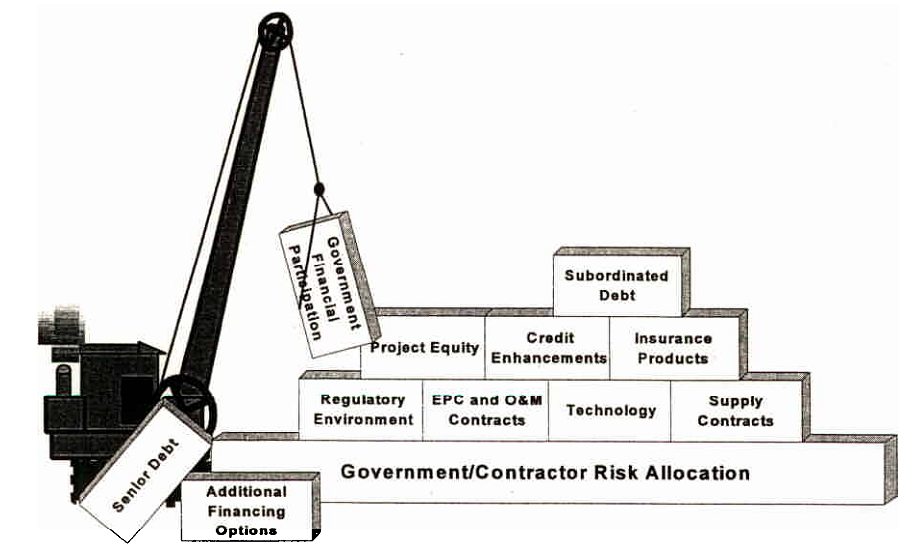

Having developed a risk allocation that provides a strong foundation for the project's success, the challenge for the government is to consider alternatives which build on this foundation and preserve its integrity. Since each project is unique, the number and combinations of potential options is unlimited, but generally fall into the following categories:

• In-Kind Investments: The economics of a project often benefit from in-kind investments such as the contribution of the project site, right-of-way, or natural resource. Alternatively, the government may agree to develop infrastructure improvements to the project site, serving to keep these costs out of the contractor's investment requirements. Through tax-increment-financing, municipalities often find that they can finance these improvements based on the increased tax revenues generated at the site.

• Pass-Through Costs: Recognizing that the assumption of certain costs expose the contractor to additional risks, and in turn, raise the contractor's price of providing services, governments often choose to supply services for free or allow the contractor to treat the costs as "pass throughs." For example, the government may pay for utilities or property taxes on a "pass-through" basis. By participating in tiiis way, the government eliminates any premium charged by the contractor for these services and reduces the supply risks associated with the project. While this will help the economics of the project by reducing volatility, it also shifts certain risks to the government.

• Contract Extensions: In projects where significant capital investment by the contractor is required, extending the service period can improve the economics of the project by spreading the project's fixed cost over a longer term. This allows the project investors to realize a level stream of depreciation benefits and perhaps access financing sources that provide longer debt terms. This option is particularly attractive for projects that are assuming market risk for their product because by lowering the annual fixed cost requirements, the price for the product can be more competitive.

• Financial Guarantees: There are a host of financial guarantees that governments can make to improve the project's feasibility. These guarantees can be placed on a portion of the project's debt or equity and can be crafted to address specific risks and/or events. For example, the procedures under the FAR for a "termination for convenience" constitute a partial guarantee for project costs. Often investor and lender confidence in a project can be improved by providing guarantees for specific events and risks and clearly defining the payment mechanics of these guarantees. In international projects, loans from multilateral banking institutions are usually guaranteed by the central government and commercial loans are often guaranteed for certain risks by export credit agencies such as the U.S. Export-Import Bank or the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC).

• Fixed Payment Mechanisms (Revenue Guarantees): Project lenders and credit rating agencies apply significant scrutiny on the payment mechanisms provided in project agreements and will look for fixed payments which maintain debt service coverages under all foreseeable circumstances. In waste processing facilities, for example, contracts typically have "put-or-pay," "availability," or "capacity payment" provisions, each of which requires minimum payments that are unrelated to actual throughput. Depending on the level of volatility associated with the feedstock or other critical supplies provided by the government, the agreements may call for a "true-up" at the end of a period to ensure the government is not overpaying. This type of provision insulates creditors from the risks associated with revenue volatility, which is a critical requirement for financial feasibility.

• Project Loans: In order to preserve the structure of the financing, the government may provide loans to the project. Generally, this participation is most useful on a subordinated basis (i.e., a subordinate position to the senior lenders) because it will provide a substitute for more expensive debt and it avoids inter-creditor issues associated with the collateral value of the project's assets. By providing a subordinated loan, a government can fill important gaps in the project's financing and can maintain the equity committed by the contractor.

• Project Equity: The government also can play a role as an equity investor to the project. This has been done on international infrastructure projects and improves the project's economics while preserving the incentive structure of the project. If, for example, the government recognizes that experience curve effects will lead to efficiency improvements in a privatized waste processing facility and is concerned about the generation of excess profits, it can participate in the project as an equity investor. This will entitle the government to a share of those returns.

• Advanced Payments: Like project loans and equity investments, advanced payments represent a cash outlay to the project prior to completion of construction. In the U.S., progress payments by the government are typically associated with this option and generally have been timed With contractor's expenditures rather man performance. Of all of the financial alternatives, this option carries the greatest potential for undermining the incentive structure of the project unless linked in some way to measurable performance.

• Performance Payments: Although a type of advanced payment, performance payments are identified as a separate category because the payment trigger is usually linked to contractor performance on the project. In much the same way as cash outlays on a construction loan are staged and released based on progress, performance payments can be based on completion of project milestones. Like other types of advanced payment mechanisms, this category can threaten the risk allocation structure. However, it also can be used strategically to address specific objectives. For example, options to consider include

- providing cash payments during development or permitting

- providing co-payments during development or permitting

- funding a portion of the engineering and design

- providing a performance payment at the end of design

- providing a portion of the construction funding

- investing equity in the project company which is then repurchased by the private entity after startup

- purchasing the facility after startup

- providing funds for pre-payment of major equipment items that might revert to the government in the event of performance problems at the facility

- pre-funding a portion of the operations and management budget during the startup period.

The options outlined above can be applied with precision to bridge a gap in the project's financial structure. As depicted in Figure 4, often these options can build on commercially available financing alternatives to improve the project's attractiveness to private capital.

In some cases, incorporating one or more of these alternatives is necessary simply to make the privatization feasible, and in other cases, it can fine-tune the economics of the transaction. However, as discussed above, substitution of public financial resources for private financing can alter the risk allocation and prove more costly in the long run. Therefore, when developing the options, it is important to consider participation as just as another step in the allocation of risk for the project and to use appropriate caution.

Figure 4. Financial Layering