PPP Program Evolution

Each of the PPP programs has evolved since it began. While institutional learning has certainly occurred by experience, it has also come via external and internal scrutiny of the programs. Hence, the program changes have not manifested themselves just through the adjust- ments in organizational practices that occur naturally as familiarity with conditions and circumstances increases, but also through modifications to law and policy.

For instance, Spain's Law 13/2003, passed in May 2003, was established to reinforce private financing of public facilities and to improve the legal framework by defining a new risk- sharing approach, particularly for the risks involved in estimating traffic demand .(e) This law, among other things, established the principle of recalibrating the economic terms of the PPP contract. The law "specifies which events may cause the modification of the economic terms of the contract in order to rebalance the financial terms of the concession. Consequently, the bidders know, at the time of preparing their offers, which specific cases may lead to changes in the contract conditions initially stated."(e) This is a significant shift in how uncertainties throughout the project life cycle are managed, especially the traffic demand risk that can be challenging to forecast for a new toll road.

The United Kingdom's PFI has been the subject of tremendous scrutiny by its National Audit Office (NAO) and Parlia- ment. The first of 50 NAO reports on PFI was issued in 1998. While this report concluded that value for money (VfM) through PFI projects was being achieved, it also found grounds for improvement in risk allocation, contract provisions, etc. With time, the United Kingdom has implemented a variety of changes designed to improve its PPP program. A standard PFI contract is now used, and approval is required if contract deviations are sought. National employment legislation exists to protect public employees if an existing asset or service is transferred by contract to a private provider or operator. In effect, they must receive a comparable opportunity and benefits with the private service provider. Finally, contract modifications over such long-term agreements are inevitable as standards and expectations change, so current and future contracts provide more flexibility to negotiate changes. The Highways Agency, in particular, has learned that it makes sense to revisit contracts more frequently to assess potential changes rather than allow changes to accumulate and attempt to negotiate a major modification.

Similarly, New South Wales adopted new policies following external scrutiny. Public reaction to the opening of the Cross City Tunnel in 2005 prompted a Review of the Future Provision of Motorways in New South Wales by the Infrastructure Implementation Group of the Premier's Department (commonly referred to as the "Richmond Report"). The report examined seven prior PPP motorway projects in the Sydney metropolitan area. While the report concluded that the RTA had generally complied with existing policies and procedures, it made a number of recommendations. As a result, the government of New South Wales has made several changes in its PPP policies and practices-refocusing its emphasis on value

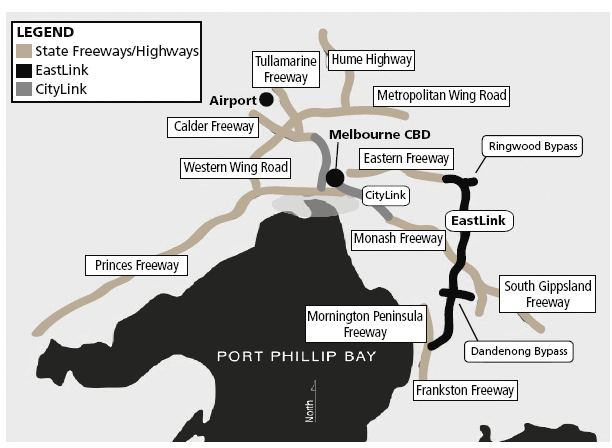

Figure 6. PPP highways in Victoria.

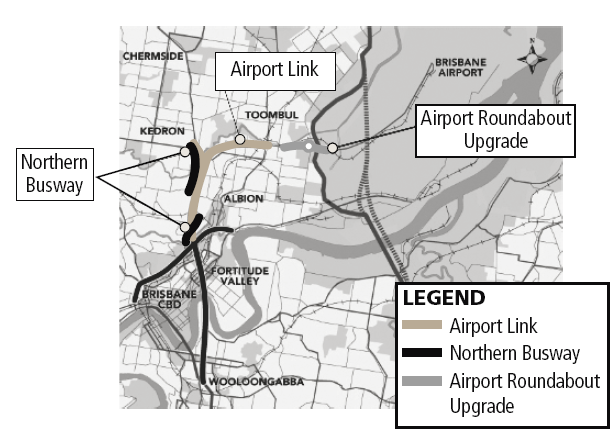

Figure 7. Queensland’s AirportLink/Northern Busway PPP

for money for its roadway users, improving overall transparency by disclosing all contract documents and amendments, and abandoning the no-net-cost- to-government policy.

Earlier, Victoria built on its 1990s experience while also drawing on the knowledge of countries such as the United Kingdom when it issued its Partnerships Victoria policy in 2000. This policy represented a fundamental shift in the state's perspective and implementation of PPPs. Foremost, the policy established a clear aim of achieving value for money in the public interest, made no presumption that the private sector was more efficient in building and operating public assets, and emphasized optimal rather than maximum risk transfer to the private sector. Since promulgating this policy, Victoria has issued a variety of publications on PPP procedures, ranging from practitioner's guides to contract management frameworks. Perhaps the strongest indicator of the maturity of its overall program is reflected in its project selection policy. Budgetary funds must be available to support any potential infrastructure project for it to be considered for inclusion in a capital program. If the potential project has the attributes necessary for a PPP, then it will be evaluated through Victoria's "Value for Money" guidelines. Only if the project demonstrates value for money as a PPP will it proceed that way. Otherwise, Victoria's provincial budgetary funds will be used to finance its conventional delivery3

Similar to the United Kingdom, the Australian national government is working on a standard PPP contract by infrastructure sector, due in 2009. Some host country representatives viewed moves toward standardization in procedures and contracts as somewhat troubling. While standardization can promote stability and reduce transaction costs, too much standardization, especially in contracts, can limit flexibility, effectively reducing avenues to structure PPPs as unique service arrangements. Instead, some representatives suggested dissemi- nation of process guidelines for project definition and selection, procurement, and award coupled with a reasonable number of standard contract provisions to promote essentially the same end: market reliability and transaction cost reduction.

____________________________________________________________________________________

3 It is worth noting that this was the policy described by Victorian officials; whether this policy is being followed is unknown. Still, the mere existence of such a policy suggests a radically different political view of PPPs than in the United States.