Managing the Partnership

Given that the PPP contracts observed ranged from 25 to 50 years with the typical term from 30 to 40 years, the relationship between the public and private sectors is indeed a long-term one. This circumstance puts managing the partnership at the forefront. Clearly, the partnership arrangement most tangibly manifests itself in contract management practices.

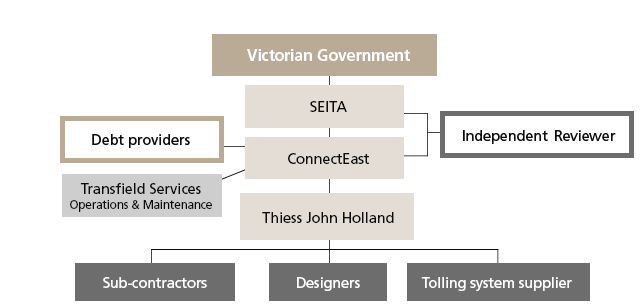

These practices are split into the capital delivery and operations phases. During design and construction, all of the host nations employ an independent verifier who serves as an objective third party to administer (certify pay requests, etc.) and review (check compliance with requirements, make onsite visits, etc.) the project, as illustrated in figure 17. Payment policies for the independent verifier varied among countries. In most cases, the government and the PPP contractor share this cost. In one case, however, the PPP contractor covers this cost up to a threshold amount, above which the cost is shared. Since verifiers are often paid on a fee basis, the logic is that higher verification costs indicate inadequate performance by the contractor, so bearing this cost serves as an incentive.

While management of capital delivery is certainly important, the crux is contract management during the operations phase. This crystallized for the scan team

Table 8. Adjustments to payment mechanism to M25 PPP contractor in the United Kingdom.

| KPI Area | Measurement |

| Lane | Deductions for lanes closed |

| Route | Monthly deduction or bonus |

| Condition | Deductions for: |

| Safety | Annual deduction or bonus |

| Proactive | Annual bonus |

when a department's representative (DR) in the United Kingdom briefed the team about his role and responsibilities as the Highways Agency's long-term contract manager. His knowledge and skills were clearly evident, as was his significance to maintaining the partnership with the private contractor as intended. Technically, the DR has three key roles: (1) performance monitoring, (2) financial monitoring, and (3) contract administration. On the surface, these appear similar to those of an owner's representative on a typical construction project. If one scratches below the surface, however, it becomes clear that the DR must carefully balance the relationship with the PPP contractor with the intended contract requirements, risk allocation, and service standards over a substantial time period. Moreover, the DR must do this with modest in-house support staff. The other countries visited have similar positions, such as the government delegate in Spain.

Table 9 (see page 44) summarizes basic contract management roles, responsibilities, and examples during the operations phase. Certainly, performance monitoring is a critical responsibility of the contract manager. In the United Kingdom, if the PPP contractor is not in compliance with performance standards, the DR may take five levels of action:

Figure 17. Typical role of independent verifier in PPP project.

♦ LEVEL 1: Comments and Observations The DR notifies the contractor in writing that certain requirements or standards are out of compliance.

♦ LEVEL 2: Nonconformance Report The DR files an official report on contractor noncompliance with requirements or standards.

♦ LEVEL 3: Remedial Notice

The DR puts the contractor on notice that if compliance with requirements or standards is not achieved within a certain timeframe, penalty points will be assessed.

♦ LEVEL 4: Penalty Point Notice The DR files a report and the contractor is assessed penalty points for noncompliance.

♦ LEVEL 5: Warning Notice

The DR informs the contractor of potential significant contractual actions that may occur; this may eventu- ally trigger the government's step-in rights.13

Certainly, noncompliance issues are best handled quickly and with the least amount of disruption. To date, the United Kingdom has not had to proceed to Level 5 with any PPP contractor.

Aside from these aspects of operations contract manage- ment, a key aspect is recognizing who retains what risks and making sure the contract manager's actions do not inadvertently make the public sector liable for a risk allocated to the PPP contractor. The DR in the United Kingdom provided a good example. In the contract that he manages, the private partner is responsible for road- way availability during winter weather, so essentially the contractor bears the risk of keeping the roadway clear of snow and ice. During a particularly bad storm, the contractor was unable to get its snow removal equipment up a steep grade, so a portion of roadway had to be closed until the weather cleared. The contractor was penalized for this service failure. Later, harsh weather was forecast, and the PPP contractor consulted the contract manager on how to keep the same thing from happening again. Rather than prescribing what he thought the contractor should do, the contract manager first reminded the contractor that it was its responsibility to keep the roadway clear. Through a careful dialogue the contractor came to the conclusion that it should pre-position the snow-removal equipment near the crest of the steep grade. In the course of this fairly routine interaction, the DR did not step into the contractor's shoes and potentially expose the Highways Agency to any claims for cost due to DR directives.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

13 Step-in rights grant the government the contractual remedy to take over the contract from the service provider.