Public-Private Partnerships: Virginia's Enabling Legislation

In 1988, the General Assembly approved legislation to allow private companies to build and operate for-profit toll roads on Virginia's interstate system.20 Construction on such a project, the Dulles Greenway, began in 1989 and completed in 1995. The State Corporation Commission sets the Greenway toll rates to allow for a reasonable rate of return for the investors. The same year the Greenway opened, the General Assembly passed the Public Private Transportation Act (PPTA), a comprehensive update and overhaul of the original PPP legislation.

The PPTA is the legislative framework enabling VDOT to enter into agreements with the private sector to "construct, improve, maintain, and/or operate qualifying transportation facilities."21 The legislative guidelines state that a six-phase evaluation process must review any solicited or unsolicited proposals: 22

1. Quality Control - Does the proposal meet the needs of the local, regional or state transportation plans in a timely manner with greater efficiency and less cost than the public sector? Does the private sector demonstrate risk-sharing and/or cost responsibility?

2. Independent Review Panel (IRP) - Members of the CTB, VDOT representatives, transportation officials, and knowledgeable members of the academic community evaluate the proposal based on an explicit set of evaluation and selection criteria. The IRP

recommends whether any of the proposals should advance to the detailed proposal stage.The IRP phase includes opportunities for comments from the public and affected localities.

3. CTB Recommendation - The CTB reviews the IRP endorsed conceptual proposals and makes a recommendation to VDOT whether to advance any of the proposals to the detailed phase and further evaluation.

4. Submission and Selection of Detailed Proposals - A VDOT review committee evaluates the recommendations and may request that none (no build option), one, or more private sector firms submit detailed proposals and enter into competitive negotiations.

5. Negotiations - The public and private sectors negotiate an interim and/or comprehensive agreement that details the rights and obligations of the parties, set a maximum rate of return to the private sector, determine liability, and set dates for transfer of the facility from the private sector back to the Commonwealth.

6. Interim and/or Comprehensive Agreement- After negotiations and the state selects the preferred private firm, both parties sign an interim agreement. The interim agreement provides legal notice to proceed with traffic and revenue studies, project submission for the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA) Evaluation, and solicit public comments. After the steps are complete and negotiations finalized, a comprehensive agreement is finalized and the Record of Decision (ROD) is issued.

The PPTA implementation guidelines seek to "encourage investment in the Commonwealth by private entities by creating a more stable investment climate and increasing implementation guidelines promote competition to create multimodal and inter-modal solutions; increase flexibility in the development of interim agreements to accelerate required activities; and required greater commitments or guarantees by proposers with mandatory risk sharing." 23 Furthering these implementation guidelines and promoting PPPs, the 2005 amended PPTA legislation does the following:

• Authorizes private entities to construct and/or operate qualifying transportation facilities

• Provides for solicited and unsolicited proposals.4

• Establishes an interim agreement to provide for partial planning and development activities while other aspects of a qualifying transportation project are being negotiated and analyzed.

• Requires concession payments be used on transportation benefits for facility users.

In his May 2006 testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, Sub-Committee on Highways, Transit and Pipelines, Virginia Governor Tim Kaine outlined five guiding policies that the Commonwealth uses when considering public-private partnerships:

• PPPs are not free and someone has to pay for the new infrastructure.

• Private financing should ensure a timelier delivery of the project at a lower cost or with greater efficiency than the public sector.

• A PPP project must address a true, public need.

• Benefits of the project should accrue to those paying for the project (toll-payers, taxpayers, or risk-takers). This policy is state law that any revenue raised in the corridor must be spent on transportation projects (including transit) in the same corridor.

• Open, public transparency.

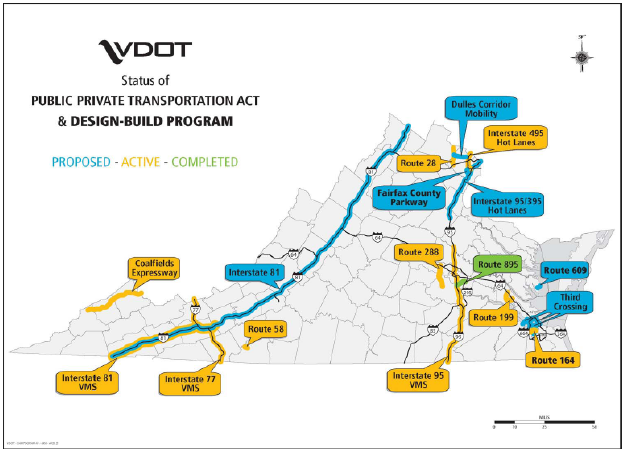

To date, Virginia has completed four highway public-private partnerships (See Figure 3 for a list of completed and active PPTA projects). Of those projects, the Greenway has operating terms that predate the PPTA (the Greenway is a privately owned road, not a leased facility). Despite the initial and promising success of PPPs as a source for supplying additional highway capacity, transportation needs still outstrip the purpose of public-private partnerships. For a PPP to be successful in Virginia, the forecasting of vehicle use and project revenue must be sufficient to attract private sector investment. That is not the case for all transportation needs. Many projects still require traditional state funding especially in rural areas where the use of the roadways is not at critical mass to warrant private sector tolling. Public-private partnerships are not a cure-all, but under the appropriate conditions, PPPs can provide additional highway lanes that otherwise would not be built.

Figure 3: VDOT Status of PPTA and Design-Build Program

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

4 The unsolicited proposal is one of the central features of Virginia's PPTA legislation that allows the private sector to invest their own capital, engineering experience, and other resources to develop an innovative, cost-conscious way to meet transportation needs.