State Budget and Appropriations Processes

A key power of the legislative branch is over budgeting and appropriations. Few if any bills on which the legislature acts are as vital as those that authorize the expenditure of public funds for specific purposes of state government. State budget processes require continuous executive-legislative interaction to maintain balance of power; this balance, however, differs from state to state.

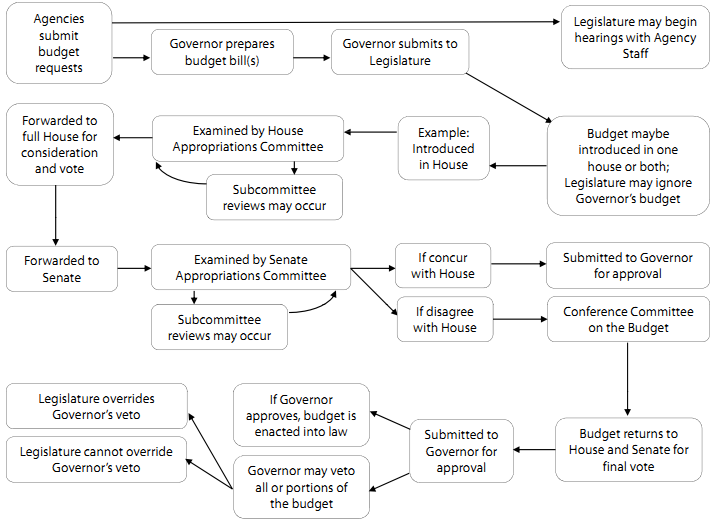

The executive and legislative branches generally participate in different stages of the budgeting process (Figure 4). Typically, the governor formulates a budget proposal based on executive agency requests and submits it to the legislature; this tends to give the executive branch the power to set the terms of the discussion. In some states, however-including Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas-the legislature produces a comprehensive budget as an alternative to the governor's proposal. In other states such as Arkansas and South Carolina, both branches contribute significantly to the budget proposal. The legislature reviews and then adopts the budget as one or more appropriations bills. The enacted budget is returned to the governor, who may veto the budget in its entirety or in part. The legislature then may vote to override gubernatorial vetoes. After the budget becomes law, executing it is generally an administrative function, and overseeing it is a legislative one.35

DOTs and other executive agencies participate in the budgeting process first by submitting budget requests to the office of the governor for consideration and incorporation into the executive budget request. In all but eight states and Puerto Rico, executive agencies also submit budget requests directly to a legislative committee or office.36 DOTs may be given more or less discretion at this stage of the process. In some cases-Colorado, for example-a transportation commission or other body must approve the DOT budget proposal. DOTs also interact directly with the legislature by appearing at budget hearings that involve substantial interaction between legislators and agency representatives. These hearings allow legislative appropriations committees to learn about executive program objectives and budget requests. They also afford agencies an opportunity to present their achievements and defend their programs to both the legislature and the public.

|

Figure 4. Typical State Budget Process

Source: NCSL, 1998. |

The budget process not only provides for a review of past appropriations and an examination of budget requests, but also serves as a key legislative oversight activity-especially in states where the legislature approves program or project-specific appropriations. In many cases, state law requires the DOT to provide reports to the legislature to inform the process (see Reporting Requirements on page 18). Some legislatures base funding levels at least partly on performance data or other information received from DOT officials in budget hearings. Further, states may establish future performance goals and objectives as well as new reporting requirements in the budget bill. In some cases, funds may be withheld contingent upon submission of a specified report or DOT action. In many states, the appropriation process is therefore seen as the main mechanism for legislative oversight of the DOT. One survey respondent warned, however, that a focus on the year-to-year budget process can detract from a legislature's capacity for broader, long-term DOT oversight.

In practice, although some legislatures can significantly influence DOT spending levels, others have only a limited ability to do so. In many states, federal transportation funding flows directly to the DOT, with little or no legislative involvement (see Federal Transportation Funding, starting on page 22). In addition, state funds for transportation often are provided through dedicated funds or revenues that allow little room for budgeting flexibility (see State Transportation Funding, starting on page 24). States also may have specific limits on legislative power. In Maryland, for example, the legislature can reduce but not add appropriations for specific projects in the governor's budget; expenditures can be added only through a supplementary appropriations bill if matched with new revenues (see State Profiles). Across the board, expenditures that derive from bonding typically are dealt with separately from the overall budget and are not subject to the same types of controls.

Many other differences exist among the states in terms of interactions between the legislature and the executive branch in the appropriations process. States vary in their budgeting approaches and assumptions, the amount of time agencies have to prepare proposals and other entities have to review them, the entity that writes the appropriation bill that is introduced in the legislature, procedures for making supplemental appropriations when the legislature is not in session, control over federal funds, and gubernatorial veto authority, among others. These variations-detailed in NCSL's Budget Procedures online resources37-further contribute to each state's unique separation of governmental powers concerning state budgets and expenditures.