Innovative Finance

Table 7. Transportation Finance Mechanisms | A variety of factors have negatively affected the ability of traditional transportation revenues-federal-aid funds, state fuel taxes and other related taxes and fees-to provide needed transportation infrastructure and maintenance. In this environment, states are turning to a host of innovative finance mechanisms to help leverage traditional funding sources (Table 7 and Table 8; see also State Profiles).53 |

State Bonding and Debt Instruments | |

Public-Private Partnerships ∙ Pass-Through Tolls/Shadow Tolling ∙ Availability Payments ∙ Design-Build-Finance-[Operate]-[Maintain] Delivery Models ∙ Build-[Own]-Operate-Transfer and Build-Transfer-Operate Delivery Models ∙ Long-Term Lease Concessions | |

Federal Debt Financing Tools ∙ Grant Anticipation Revenue Vehicles (GARVEEs) ∙ Private Activity Bonds (PABs) ∙ Build America Bonds (BABs) | |

Federal Credit Assistance Tools ∙ Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) ∙ State Infrastructure Banks (SIBs) ∙ Section 129 Loans | |

Federal-Aid Fund Management Tools ∙ Advance Construction (AC) and Partial Conversion of Advance Construction (PCAC) ∙ Federal-Aid Matching Strategies Flexible Match | |

Other Innovative Finance Mechanisms ∙ Non-Federal Bonding and Debt Instruments ∙ Value Capture Arrangements such as Tax Increment Financing (TIF) | |

Sources: AASHTO Center for Excellence in Project Finance, 2008; Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) Office of Innovative Program Delivery, 2010; and Rall, Reed and Farber, 2010. |

Table 8. State-By-State Transportation Finance Mechanisms

|

State/Jurisdiction |

General Obligation or Revenue Bonds |

GARVEE Bonds |

Private Activity Bonds (PABs) |

Build America Bonds (BABs) |

TIFIA Federal Credit Assistance |

State Infrastructure Bank (SIB) |

Design-Build |

Other |

|

|

• |

• |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

• |

• |

• |

|

• |

|

||||

|

• |

• |

|

|

|

• |

|

|||

|

• |

• |

|

|

|

• |

|

|||

|

• |

• |

|

|

|

• |

|

|||

|

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

Creation of non-profit, quasi-public entities |

|||

|

• |

• |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

• |

• |

|

• |

|

• |

|

|||

|

• |

|

• |

• |

• |

|

||||

|

• |

• |

|

• |

|

• |

|

|||

|

• |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

• |

• |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

• |

|

• |

• |

|

|

|

|||

|

• |

|

|

|

|

• |

|

|

||

|

• |

|

|

|

|

• |

|

|

|

|

|

• |

|

|

• |

|

• |

|

Special tax districts |

||

|

• |

• |

|

• |

|

|

|

|

||

|

• |

|

|

• |

• |

|

Creation of non-profit, quasi-public entities |

|||

|

• |

• |

|

|

|

• |

|

|||

|

• |

|

• |

|

|

|||||

|

• |

• |

|

|

|

|

Creation of non-profit, quasi-public entities |

|||

|

• |

|

• |

|

• |

|

|

|||

|

• |

|

|

|

|

• |

|

|||

|

• |

• |

• |

• |

|

|

|

|||

|

• |

• |

|

• |

|

• |

Creation of non-profit, quasi-public entities |

|||

|

• |

• |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

• |

|

|

|

|

• |

|

|

|

|

|

• |

|

|

• |

|

|

||||

|

|

• |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

• |

• |

|

• |

|

|

|

|||

|

• |

• |

|

|

|

• |

|

|

||

|

• |

|

|

|

• |

• |

|

|||

|

• |

• |

|

|

• |

• |

|

|||

|

• |

• |

|

|

|

• |

|

|

||

|

• |

• |

|

• |

|

• |

|

|

||

|

• |

• |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

• |

• |

|

• |

|

• |

|

|||

|

|

|

• |

|

• |

|

|

|||

|

• |

• |

|

|

• |

• |

Creation of non-profit, quasi-public entities |

|||

|

• |

|

|

|

• |

• |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

• |

|

• |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

• |

|

|||

|

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

Creation of non-profit, quasi-public entities; other |

||||

|

• |

|

|

• |

|

• |

|

|||

|

• |

|

|

|

|

• |

|

|

||

|

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

Creation of non-profit, quasi-public entities |

|||

|

• |

|

• |

|

• |

State-funded rail bank |

||||

|

• |

• |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

• |

|

|

• |

|

• |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

• |

|

|

||

|

• |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

• |

• |

|

|

• |

• |

|

Key:

SP - See State Profiles for clarification or more information.

Sources: NCSL-AASHTO Survey Data, 2010 - 2011, supplemented by original research using Westlaw; AASHTO Center for Excellence in Project Finance, 2010; Dierkers and Mattingly, 2009; and Rail, Reed and Farber, 2010.

Some of these mechanisms-such as state infrastructure banks and debt financing instruments-require enactment of state authorizing legislation before a state agency such as a DOT can use them. Enabling legislation grants and defines the legal authority of an executive entity to use a given tool or program and also can address restrictions that exist in current law or policy. Debt financing mechanisms that are available to states and may require enabling legislation include general obligation, revenue, special tax and private activity bonds (PABs), among others. Most states rely on debt to finance projects; only Iowa, Montana, Nebraska and North Dakota reported relying solely on pay-as-you-go financing.54 Other states-including Illinois, Maine, Oklahoma and Vermont-specifically noted legislative approval requirements for bonding or other financing (see State Profiles). Requiring enabling legislation before a DOT can use these options gives the legislature an ongoing role in-and additional means for oversight of-transportation finance.

Other innovative financing tools can entail ongoing involvement of both state legislatures and DOTs beyond passage of enabling statutes. One such mechanism is public-private partnerships (PPPs or P3s). According to a widely adopted definition from the U.S. Department of Transportation, PPPs are contractual agreements between public and private sector partners that allow more private sector participation than is traditional in infrastructure delivery; in some, the private sector also finances some or all of a project.55 PPPs cover more than a dozen project delivery and finance models, ranging from minimal to substantial private sector involvement. The enhanced private role in public infrastructure that characterizes PPPs has made these agreements controversial, but they also are seen as an opportunity to help leverage increasingly limited public sector resources.

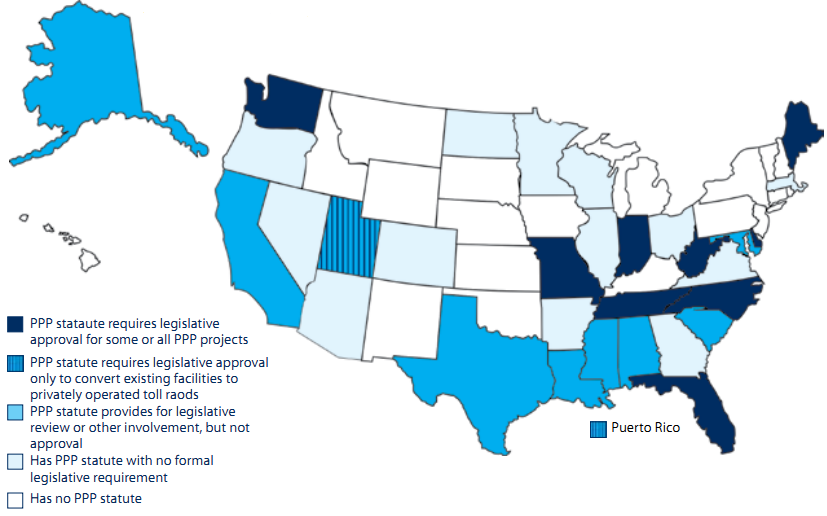

Both state legislatures and DOTs are involved in the PPP decision-making and implementation process. Legislatures are primarily responsible for deciding whether a state is to engage in PPPs and for enacting enabling statutes that permit them; as of April 2011, 31 states and Puerto Rico56 had enacted such statutes. Executive agencies such as DOTs generally are responsible for implementing PPP programs and projects within statutory guidelines.

Laws in Delaware, Florida, Indiana, Maine, Missouri, North Carolina, Tennessee, Washington and West Virginia, however, give the legislature a more active and ongoing role by requiring some form of legislative approval for at least some PPP projects (Figure 6).57 (In addition, Utah and Puerto Rico require legislative approval only to convert existing facilities to privately operated toll roads.) Legislative approval requirements vary widely. Some require approval by the full legislature and others-such as those in Delaware and Missouri-only by certain committees or committee chairs. They also differ in the projects for which approval is required, the procedures for acquiring approval and the stage of project development at which approval must be given.

|

Figure 6. PPP Enabling Statutes and Legislative Approval Requirements

Sources: Rall, Reed and Farber, 2010; N.D. Cent. Code §§48-02.1-01 et seq.; and 2011 Ohio Laws, House Bill 114. |

PPP legislative approval provisions have been heavily debated. On the one hand, they create a means for elected officials to review and be held accountable for PPP projects that may have a significant impact on the public interest. They also introduce political uncertainty into the PPP process, however, which can discourage private investors. Other options for legislative involvement in PPPs include provisions that require legislative review but not approval of PPP projects-now the model in eight states-and strong enabling legislation that addresses key policy issues in depth.58

Grant anticipation revenue vehicles, or GARVEEs, are another innovative finance tool that can require ongoing involvement of the legislature through approval provisions in enabling statutes. A GARVEE is a federal debt financing instrument that enables a state, political subdivision or public authority to pledge future federal-aid highway apportionments to support costs related to bonds and other debt financing. Essentially, GARVEEs allow debt-related expenses to be paid with future federal-aid funds, thus accelerating project design and construction. Twenty-nine states and Puerto Rico have issued GARVEE debt; Florida, Nevada, New Hampshire, Texas, Washington and the District of Columbia had authorized but not yet issued GARVEEs as of 200959

As with PPPs, in some states-including Idaho, Louisiana, Maine and Washington-the enabling statutes require further legislative approval or appropriation before GARVEE debt can be issued. In contrast, Colorado's statute explicitly delegates this authority to the executive branch.60 However, Colorado law authorizes GARVEE debt only up to a specified level and would require additional legislative approval for the DOT to exceed the cap; California also limits GARVEE issuance in statute.61