Transportation Planning

States determine their investment priorities for state and federal transportation dollars through structured planning processes that include project identification, selection, prioritization and approval. Both DOTs and legislatures can play a role in this important activity, and the balance of legislative and executive authority varies widely across states, as do the processes themselves. | |

In all states, DOTs generally take the lead in conducting transportation planning activities and ensuring compliance with federal and state requirements. To receive federal transportation funding, each state must organize its planning process to comply with federal laws, regulations and executive orders that require or influence many elements of the planning process (Table 9). The federal government requires each state to produce a statewide, intermodal long-range transportation plan (LRP). The plan provides a vision and a framework over a horizon of at least 20 years. Each state also must produce a Statewide | Table 9. Federal Laws that Influence Federal Surface Transportation Authorization Legislation ∙ Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU) ∙ Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21) ∙ Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991 (ISTEA) Other Federal Laws ∙ Clean Air Act (CAA) and Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990 (CAAA) ∙ Vision 100: The Century of Aviation Act (Vision 100) ∙ Wendall H. Ford Investment and Reform Act for the 21st Century (AIR-21) ∙ National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) ∙ Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) ∙ Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ∙ Environmental Justice Orders - Executive Order 1298 - DOT Order on Environmental Justice to Address Environ-mental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations (DOT Order 5610.2) - FHWA Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations (DOT Order 6640.23) ∙ 23 U.S.C.§ 109(h) ∙ The Uniform Relocation Assistance and Real Property Acquisition Policies of 1970 Source: Connecticut Department of Transportation, 2007. |

Transportation Improvement Program (STIP) that lists all projects a state expects to be funded with federal participation over a period of not less than four years. The process for these plans must include coordination with metropolitan planning areas and multi-state efforts; consideration of concerns of regional, local, tribal and federal land management entities (Figure 7); compliance with environmental standards; public involvement; and other requirements. States also must develop federally mandated environmental plans and reports, planning work programs, and highway safety plans and reports.62

Figure 7. Participants in the Transportation Planning Process

|

General Policy, Planning

|

Cooperative State and Local

|

Coordination with

|

|

• Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) • Federal Transit Administration (FTA) • National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) • Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) |

• State DOT • Other state agencies • Partners in multi-state efforts • Transit operators • Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs) • Regional [Transportation] Planning Organizations (RTPOs or RPOs) • Local governments • Local community organizations and agencies |

• Citizens • Affected public agencies • Representatives of public transportation employees • Freight shippers • Private providers of transportation • Representatives of public transportation users • Representatives of users of pedestrian walkways and bicycle facilities • Representatives of persons with disabilities • Federally recognized Indian tribes and the Secretary of the Interior • Other interested parties |

Source: Adapted from Connecticut Department of Transportation, 2007.

Transportation planning processes are further defined at the state level. Thus, in addition to federal requirements, DOTs must meet state-specific mandates concerning transportation plans and capital programs. In many states, DOTs must prepare one or more state plans in addition to those that are federally required. In New Jersey, for example, the DOT must annually prepare and submit to the legislature a proposed transportation capital program for the ensuing fiscal year, and must also separately update the federally required STIP. DOTs also may be required by state law to prepare other mode-specific plans-for example, for rail, aviation, or bicycles and pedestrians.

The extent of legislative involvement and authority in the process of selecting and approving projects differs greatly across states. At one end of the continuum are Nebraska and Wyoming, which constitutionally prohibit the legislature from prioritizing specific road projects.63 At the other end are: Delaware, where legislators each determine the use of an annual authorization of the state's Community Transportation Fund for transportation-related projects in their respective districts; Pennsylvania, where legislative leaders serve on the state Transportation Commission that approves all projects; and Wisconsin, where the legislature is required by statute to review and approve major highway projects.64 In other states-including Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Louisiana, Maryland, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Rhode Island, Tennessee and Vermont-the legislature actively reviews or approves DOT plans or programs, often as part of the budget process (see State Profiles).

Between these poles are many other ways in which legislatures are involved in transportation planning. Arizona, Connecticut, Florida, Kansas, Maryland, South Carolina, Texas, Utah and Vermont have set forth in statute general planning priorities or processes. The Kansas legislature also approves the state's comprehensive transportation plan, which provides only general priorities rather than specific projects. Legislatures in Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Idaho, Iowa, Massachusetts, Minnesota,65 Montana,66 Nevada, Tennessee, Oregon, Utah, Virginia, Washington and West Virginia have sometimes prioritized projects by enacting project-specific earmarks or bond bills, whereas those in Ohio, Oklahoma, Kansas and South Dakota have generally chosen not to legislate in this way. In California, Indiana, Missouri, Montana, North Dakota, South Carolina and South Dakota, there is generally little or no direct legislative role, beyond the opportunity for legislators to participate in hearings or meetings as members of the public. In these states, because funds flow directly to DOTs without legislative involvement or are appropriated at the agency or program level rather than to specific projects, the legislative role in project prioritization is further limited.

Other notable models for involving state legislatures in transportation planning include the following.

∙ In Louisiana, the legislature holds hearings around the state and reviews the proposed construction program. Committee feedback is used to modify proposed programs or to develop future ones. The legislature can delete but not add or substitute projects in the approval process.

∙ The Connecticut legislature created a Transportation Strategy Board in 2001. This board includes legislatively appointed members and proposes a transportation strategy for legislative approval every four years.

∙ In North Carolina and Oklahoma, the DOT selects highway projects, but the legislature directs funds to other modes such as transit and rail as part of the appropriation process.

∙ The Rhode Island legislature does not have an active role in prioritizing federally funded projects, but does when state capital funds are used.

∙ Legislators in some states, including Pennsylvania and Virginia, have been appointed to the boards of metropolitan planning organizations and so have participated in the planning process in that way.

|

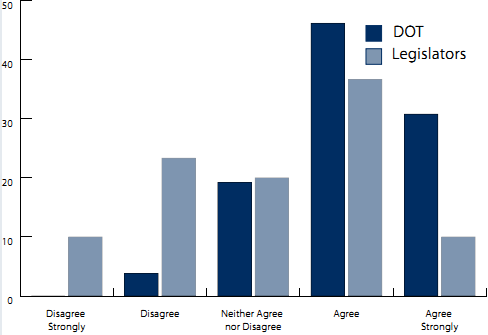

Key Survey Finding: Seventy-seven percent of DOT officials surveyed agreed that transportation projects are chosen based primarily on merit, not political, personal or other considerations. Responses from legislators were divided. Note: See page 2 for a description of this survey's methodology and data limitations. Transportation projects in my state are chosen based primarily on merit, not political, personal or other considerations.

Data expressed in percentage of legislator or DOT respondents |

A key theme in the NCSL-AASHTO survey data was the particular tension between legislatures and DOTs about what constitutes an appropriate level of legislative involvement or oversight in the critical task of transportation planning. State legislators and DOT officials identified a desire to have appropriate checks and balances in place to depoliticize the process and to prevent promotion of "pet projects" at the expense of the entire system. Despite these concerns, 77 percent of DOT executives agreed that transportation projects are chosen based primarily on merit, not political, personal or other considerations; responses from legislators, however, were divided (see Key Survey Finding on the previous page).