Design-Bid-Build (DBB)

This is the traditional form of project delivery where the design and construction of the facility are awarded separately and sequentially to private sector engineering and construction firms. As a result, the DBB process is divided into a two-step delivery process involving separate phases for design and construction. Under a DBB contract, the project sponsor, not the construction contractor, is solely responsible for the financing, operation, and maintenance of the facility and assumes all design risks. The DBB selection process is based on negotiated terms with the most qualified firm for the design phase while the award of the construction contract is typically based on the lowest responsible bid price.

Most of the nation's highways have been delivered via the DBB delivery approach, especially since the Interstate Highway System program was launched in 1956. As the country's highway system evolved during the past fifty years, the traditional DBB project delivery approach became more inefficient due to the tendency for project sponsors to rush design plans to meet pre-determined bid letting schedules for construction contracts to be awarded. This promoted the introduction of design errors or omissions which were then passed along to the winning low-bid contractor, leading to subsequent change orders and extra work orders to deal with design problems and unfavorable site conditions. As a result, the low-bidder could often recoup discounts offered in the original bid price to win the contract by seeking additional funding to pay for design problems through change orders and extra work orders. By the end of the contract, the total contract cost often exceeded the original high-bid price.

To address the inflexibility and other shortcomings of the traditional DBB project delivery approach, a number of alternative project delivery approaches have evolved over the past two decades. These alternative approaches assigned ever-increasing roles, responsibilities, and risks to private sector teams able to develop and possibly finance the project. This has helped to expedite project delivery and lower project costs through the use of best practices and avoiding the effects of inflation on the cost of project materials. These alternative project delivery approaches are part of the group of contractual relationships referred to as public-private partnerships (PPPs).

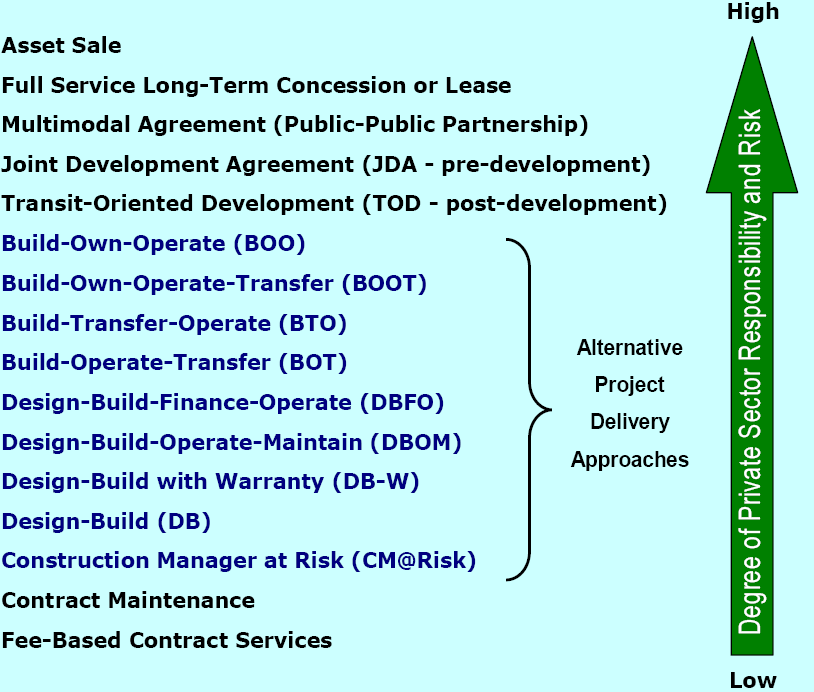

Exhibit 6 displays the spectrum of PPP approaches that share the same basic characteristic, namely: greater private sector involvement and risk-taking in the development, financing, and/or operation of transportation infrastructure than has traditionally been the case. As illustrated in Exhibit 6, PPP approaches range from staff augmentation or maintenance contracts which involve limited private sector responsibilities, to long-term lease agreements or concessions which involve maximum private sector responsibilities short of outright sale to the private sector. Since PPP approaches often involve greater private sector responsibilities and risks, the resulting contract agreements often include the opportunity for greater value capture by the private partner.

It should be pointed out that the greatest potential involvement by the private sector involves the acquisition of the public-use transportation asset by a private partner or team, shown at the top of Exhibit 6. In the United States, asset sales or Build-Own-Operate (BOO) contracts are perceived as not in the public interest. That is because once the public sector transfers ownership of a public-use transportation asset to the private sector, it loses control over how the asset is preserved or priced to the user. This raises significant policy questions for elected and appointed officials that should be addressed in evaluating what form of PPP is best to use to advance a particular project.

Exhibit 6 – Major Tyoes of Public Private Partnerships

|

|

Each of these PPP approaches and their potential benefits are described below in order of increasing private sector responsibility, risk-taking, and potential for reward.