The need for innovation in infrastructure partnerships

"We need to have an open mind about this. We need to think outside of the box."

- U.S. Department of Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood.5

With a greater number of priorities (and industries) competing for public funds in the wake of the credit crisis, governments are under more pressure than ever before to be creative about how infrastructure needs are met. If infrastructure gaps are to be narrowed, the traditional models of financing and delivering infrastructure must give way to new, innovative models and a portfolio of hybrid approaches. The structure and financing of infrastructure projects involving both the public and private sectors (public-private partnerships, PPPs or P3s) will need to evolve in response to changing conditions in the financial markets. In countries around the world, we are starting to see the outlines of what such innovations may entail.

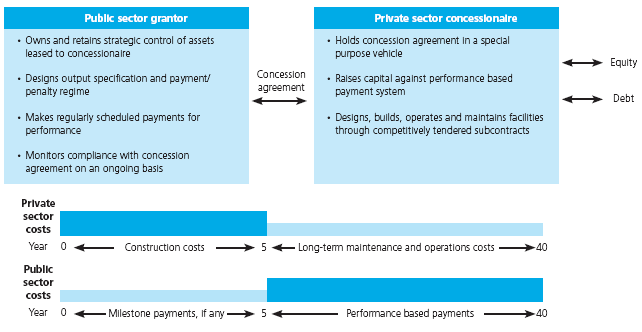

Figure 1. The "availability payment" model

• In early 2009, the Florida Department of Transportation entered into a $1.8 billion 35-year concession with a private consortium, headed by the Spanish firm ACS Infrastructure Development, to build and operate high- occupancy toll lanes near Fort Lauderdale. The financing includes more than $200 million in equity, $750 million in commercial bank debt and a $603 million loan from the federal Transportation Infrastructure Finance and innovation Act (TIFIA) program.6 In this PPP, the Florida DOT will set toll rates, retain all revenues and make "availability payments" to the private concessionaire annually out of all of its revenues (including state appropriations, tax revenues and tolls). The project is the first U.S. toll road PPP structured with performance-based availability payments (see figure 1).

• The United Kingdom is in the midst of the nation's largest-ever school buildings investment program, with a goal of rebuilding or renewing nearly every secondary school in England. To realize this ambitious goal, the central government has created a PPP model called a Local Education Partnership (LEP), a private sector consortium working in formal partnership with local authorities and the central government. Certain LEP projects are being delivered through conventional capital funding and design-build contracts, while others employ PPP models. The program is designed to capture economies of scale in delivery by bundling multiple facilities into a single procurement.

• Other innovative structures emerging around the world include the combining of multiple public authorities (such as neighboring local government entities) to procure a single project or service. The four local authorities covering the city of Dublin, for example, were keen to move away from their traditional reliance on landfills and together procured a large-scale waste-to-energy facility to meet the needs of all four authorities. The improved project economics attracted a broader array of bidders to the procurement, resulting in cost efficiencies for the local authorities. An agreement to purchase the generated power at a reduced cost is an added benefit to the authorities.

The five components of an infrastructure project |

Design. Under virtually any partnership structure the responsibility for design will be shared. For instance, even in partnership structures with high degrees of private responsibility, the public sector's articulation of performance specifications will limit the range of design options. In many projects, the need to ensure compliance with broader planning and environmental guidelines results in a significant degree of public sector design. |

Construction. This component includes the construction of the physical asset(s) over a prescribed period of time, generally at a prescribed cost. Deciding which party assumes the impact of construction cost overruns and time delays must be considered. |

Service operation. Operating the asset may include various activities from general management of service provision and revenue collection to performing soft (or non-core) services associated with an asset, such as laundry services within a hospital. Operation typically begins at the end of construction, upon agreement that the construction has been satisfactory. In PPPs, the private partner's compensation is dependent on the achievement of performance standards. |

Ongoing maintenance. Generally, there are two principal types of maintenance to be considered in any infrastructure project: ongoing regular maintenance (or operating maintenance), and major refurbishment, often called life-cycle or capital maintenance. |

Finance. This component generally includes financing for the capital costs of construction, as well as working capital requirements. |

These projects, each with its own distinct mix of public and private participation, demonstrate the diversity of delivery models available today. There is no longer a binary decision between public and private. In reality, nearly every public infrastructure project involves a large degree of private sector participation through the normal channels of a market economy. Most PPP models simply represent a way of deepening and/or broadening the private sector's engagement in delivery in exchange for sharing in the associated risks and rewards.

The question policymakers in the United States, the United Kingdom and Ireland had to answer in the above examples was not whether to involve the private sector in infrastructure projects, but rather:

What is the optimal mixture of public and private sector participation in the project to maximize public value?

This is the central question facing infrastructure policymakers today. And there's no one-size-fits-all answer for every situation.

Most infrastructure projects are composed of five elements for which responsibility must be assigned: design, construction, service operation, ongoing maintenance and finance (see nearby box). Theoretically, any of these elements and their related risks can be allocated to either the public sector or the private sector. The shape of that allocation determines the structure of the partnership.

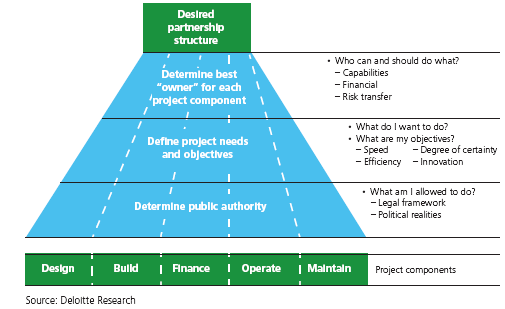

Dividing up these responsibilities in the best possible way for any given project is not easy. It requires careful qualitative and quantitative analysis. Short-cutting this process could result in suboptimal allocation and lost value. How then can public sector entities decide which project responsibilities they are best suited to retain, and which they are better off shifting to the private sector? The decision making process is depicted in the schematic (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Determining the right mix of public and private involvement in infrastructure financing and delivery

Source: Deloitte Research