4.2 Findings from review of key international jurisdictions

The following section provides a high-level summary of approaches adopted by key international jurisdictions to address some of the main issues raised by the Australian market participants in respect of barriers to competition.

Largely unknown pipeline of projects that is sporadic in nature

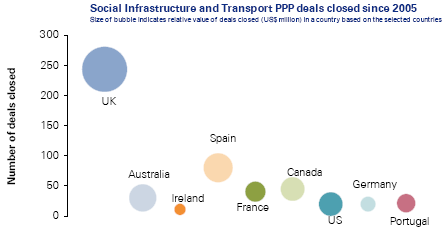

Based on literature reviewed, most international jurisdictions consider the establishment of sufficient deal flow as crucial to encouraging new firms to enter markets. Jurisdictions such as the UK, Spain and Canada are releasing multiple projects to the market annually (as depicted in the graphs below7).

Australia has closed fewer PPP deals since 2005 (in terms of number of transactions), compared with the UK, Spain, Canada and France, although the total value of deals closed is comparable to that of Spain and Canada; with the average deal size in Australia being significantly higher than other countries (for example, the average capital value of PPP deals closed since 2005 in Australia is about 3.5 times that of the UK and 2 times that of Canada).

|

Source: Infrastructure Journal (October 2009) and KPMG analysis of data |

Even after adjusting for Australia's smaller population, its pipeline falls well behind those of the UK and Canada.

According to Chan et al (2009)8, in Australia, PPPs are increasing and now constitute around 5% of investment in public infrastructure; more in NSW and Victoria (where the proportion has been around 10%). Canada delivers 10% to 20% of public sector capital investment using PPPs9 and the UK delivers about 15% similarly10.

A key success factor for the UK has been strong political will and general public acceptance of the PPP model (though opponents to it remain). The UK government has made a policy decision to use the PPP model for new investment where PPP has proven and continues to prove to be value for money (such as schools, hospitals, prisons, etc.),11 though it is not clear this policy will survive the election in May 2010. The UK also is not constrained in practice by the need for full budget funding of a project's capital costs before approval for it to proceed.

The UK Treasury has recently formed Infrastructure UK from its own PPP Policy unit, the Treasury Infrastructure Finance Unit and Partnerships UK to coordinate the country's overall approach to infrastructure development.

Canada also (generally) has a politically supportive environment ,with the federal government requiring the PPP model to be being considered as an option for large infrastructure projects receiving federal funding. The Province of British Columbia (BC) also requires consideration of the PPP model for all provincially-funded capital projects with a value in excess of C$20 million, and that procuring agencies justify any use of alternative procurement methods.12

|

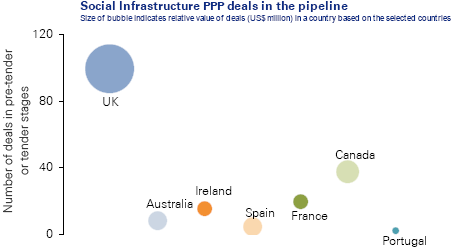

Source: Infrastructure Journal - IJ PPP/PFI Review and Outlook Q4 2009 and KPMG analysis of data |

According to a recent Infrastructure Journal report13, Canada has 43 PPP projects in the pipeline (at pre-tender and in tender stages) compared to Australia with 9 projects (3 in each of Victoria and Queensland; 2 in SA; 1 in the Federal Government). The total capital value of the deals in the pipeline in Australia is comparable to Canada, Spain and France, current projects in Australia's pipeline being relatively large in size.

Some key strategies implemented by other international jurisdictions to increase the volume of transactions include:

• putting in place a strong pipeline of smaller PPP projects under 'framework' type agreements that streamline processes and reduce bid costs in sectors with a high number of PPP projects

• maintaining a database about planned construction projects across the public sector to (for example the database of the Office of Government Commerce (OGC) in the UK) to:

- provide the market with information on when it expects projects to proceed to tendering

- monitor whether projected demand from the public sector is likely to exceed market capacity

• making key public announcements in respect of large scale infrastructure plans (such as Canada's seven-year "Building Canada" infrastructure initiative and the five-year infrastructure plan (announced in 2005) - "ReNew Ontario" - under which more than C$30 billion will be invested, with 31 projects undertaken as PPP projects, of which 27 is in the healthcare sector)

• committing to the PPP model to attract and maintain the interest of PPP market participants

• using the PPP model as an alternative approach to funding infrastructure within a fiscally constrained environment (i.e. as a driver to defer expenditure). For example, in most of the international jurisdictions reviewed, the decision about how to fund a project is not separate from the decision of how to deliver it (which is different from Australia). These jurisdictions usually measure affordability by their ability to pay the service payment obligations14.

As noted elsewhere in this report, these strategies largely are not appropriate for Australia.

General complexity of bidding processes in the Australian PPP marketplace as a key deterrent for new entrants when compared with other international jurisdictions

As noted in Section 2.2 of this report, the primary considerations driving PPP procurement in Australia have been the ability to achieve:

• value for money

• significant design innovation

• appropriate risk transfer

• superior whole of life outcomes.

These considerations contrast with those of many other international jurisdictions, where a key driver for the use of PPP procurement models is the provision of an alternative funding source when public infrastructure capital is scarce.

Market participants generally view the Spanish and Portuguese models as having simple and short processes, but with some negative implications.

• In its early PPP projects (mainly roads), Portugal evaluated bids and awarded contracts based on effectiveness (price) rather than economic efficiency (value for money). This approach resulted in (fairly) short procurement timeframes and low bid costs but left Government with a possible significant fiscal impact in the long term, as there is widespread agreement that the Government significantly underestimated the risk borne by the public sector, at least in some projects.

• The Spanish approach involves significant project development ahead of the approach to the market and, in essence, requires the private sector to provide a price for the Government's detailed requirements, with limited room for innovation. The advantages of this approach are that the process is quick and that bid costs at risk are low (for the private sector). However, a disadvantage is the risk of problems with the Government's design, leading to an increase in the capital costs of the project and a consequent "rebalancing" to restore the project company's equity IRR.

Such shorter and simpler procurement processes are not desirable in Australia if they are at the expense of the overall value for money and innovation of the projects and if the Governments retain significant project risk.

The current restrictions on the availability of finance

Many countries have established separate funds to finance PPPs or concession-based infrastructure projects and/or changed their procurement practices in order to assist them to reach financial close despite the impact of the global financial crisis, to reduce or remove bidders' need to demonstrate full financial backing for their proposals. For example:

• the UK recently established a new Treasury Infrastructure Finance Unit (TIFU) as a temporary solution to lend to PPP projects that cannot raise sufficient debt finance, which it has now merged into Infrastructure UK. TIFU provided debt finance for the first time in April 2009 for the Greater Manchester Waste PPP project (with a project value of US$1.09 billion). Market participants have noted that this is a fairly complex process involving substantial government resources. Treasury lending will mostly be on commercial terms, with the ability to provide up to 100% of senior debt, but Treasury's expectation is that lending will be less than 50%. However, future use of Government lending looks less likely in the near term, as the current pipeline contains few large projects that might stretch the capacity of the financial markets

• Canada launched a new P3 Canada Fund (Can$1.25 billion) in September 2009 to invest in PPPs using a range of financing arrangements. The fund has a limited authority with some projects, such as schools and hospitals, falling outside its mandate

• the Spanish ministry of infrastructure initiated special financial guarantees for PPP projects (mainly for a high speed train project) for an estimated amount of €15 billion

• in France, savings funds managed by the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations can provide loans, up to a limit of €8 billion, to finance PPP or concession-based infrastructure projects. It may grant these loans either directly to project companies or to local authorities making investment subsidies. The French government will also, as part of its stimulus package, provide up to €10 billion in partial guarantees for PPP projects (for no more than 80% of total funding requirement).

Some international jurisdictions have also made changes to their PPP regulatory framework, including:

• the UK issuing guidance on Preferred Bidder Debt Funding Competitions

• France reducing its requirement for 100% private sector financing to at least 50% for some projects. It has also removed temporarily the requirement for bidders to submit firm financial commitment with the final bid (RFP), and it now only requires finalisation within a certain period from selection of preferred bidder, with certain conditions.

The Canadian Council for PPPs identified a number of procurement process and funding mechanism enhancements in its recent report "The impact of Global Credit Retraction and the Canadian PPP market"15. The key recommendations from this report are:

• maintaining a national pipeline of projects in Canada, ideally organised such that the timing of projects better meets the supply of resources required to complete them. This measure should stimulate more competition and potentially a better price

• continuing to use a two-staged evaluation procurement process (i.e. technical evaluation followed by financial evaluation) to shorten the irrevocability period of financial submissions

• emphasising a stable project scope and disciplined adherence to procurement timetable

• providing a commitment to an outside date for financial close, which would allow parties to rely on timelines specified and plan accordingly. Remedies should be provided to all parties if there is a breach of timelines

• increasing due diligence on private sector sponsors to ensure that the closed deal is representative of the competitive process

• increasing the level of bid cost contributions where Government requires sponsors to incur additional costs and / or assume more risks associated with bidding committed financing

• developing a fair and objective manner to evaluate requested committed financing submissions and scoring these submissions appropriately within the evaluation process

• establishing clear and consistent definitions of refinancing risk and clearly setting out the amount of refinancing risks to be transferred to sponsors

• considering Government financial support options, including co-lending of senior debt, which needs to be passive and subordinate to private lenders' debt and not be as large as to impact risk transfer and equity returns. Similarly, governments should also consider grants and project insurance (but not be perceived as a lender of last resort or 'subsidiser')

• within the value for money analysis, refreshing input costs regularly during one or more stages in the procurement process to ensure affordability targets move in line with the market. Governments also should make the public sector comparator (PSC) available to bidders in a more transparent way to promote a clear understanding of how they derive the PSC while balancing detailed disclosure with more competitive bidding

• in order to maintain the attractiveness of the Canadian PPP market, government should not be tempted to participate as equity investor, should not reduce the number of bidders short-listed, and should not introduce funding competitions after the selection of the preferred bidder while continuing to require committed financing at the RFP stage.

Many of these recommendations are specific to the impact of the Global Financial Crisis and the funding of PPP projects (which could also apply to Australia but are outside the scope of this Review). However, some aim at strengthening Canadian PPP procurement processes generally and potentially could also apply to Australia, particularly around more rigorous adherence to timetables and processes. We have discussed these improvements elsewhere in this Review.

__________________________________________________________________________________

7 Source: Infrastructure Journal (October 2009) and KPMG analysis of data Included desalination transactions

Excluded all refinancing, disposal, privatisation, bridge loans, corporate loan, acquisition, credit facility, housing, student accommodation, aircraft, airport, ports and terminal, and car park transactions

8 Chan, C., Forwood, D., Roper, H., and Sayer, C. (2009). Public Infrastructure Financing: An International Perspective. Productivity Commission Staff Working Paper, Australian Government Productivity Commission.

9 Source: The head of Partnerships British Columbia noted that he "couldn't imagine more than 10 or 20 percent of all the capital projects that the Government does being done in a P3 way." Province of British Columbia Executive Council, Transcript

10 Source: IFSL Research, PFI in the UK: Progress and Performance, p. 1. The 15 per cent figure refers to PFI deals.

11 Source: A report by HM Treasury - PFI: meeting the investment challenge (July 2003)

12 Source:: The Impact of the Global Credit Retraction and the Canadian PPP Market, deliberations by the industry members of the Canadian Council for Public-Private Partnerships, published Spring/Summer 2009

13 Source: IJ PPP/PFI Review & Outlook Q4 2009 - A detailed report on PPPs in Europe, the Malay Peninsula, Australasia and Canada.

14 European Union countries need to comply with European Union (EU) convergence criteria, which places limits on public debt and budget deficits (EUROSTAT, the EU's statistical agency, generally counts payments of PPP service charges as operating payments, rather than capitalising them and counting them as part of countries' debts)

15 Spring/Summer 2009