5.1 Feedback received from discussions with PPP practitioners

The following issues focus on those impacting bid costs incurred by the market from release of EOI to announcement of preferred bidder. Bidders generally do not consider costs incurred post-appointment of preferred bidder to be at risk (assuming successful negotiation and resolution of outstanding issues as well as Governments' commitment to the project). However, inefficiency in the procurement process post-appointment of preferred bidder still negatively impacts value for money outcomes, as these costs are included within the overall tender price and continue to add to Government's internal transaction costs.

What do you consider are the key contributing factors to inefficiencies within the Australian PPP procurement process?

As noted above, most Participants view Australian PPP procurement processes as being generally efficient, but not consistently so. The key factors raised by all Participants in relation to the efficiency of the Australian PPP procurement processes are:

• the skill and expertise of the Government team managing the procurement process

• the Government's level of commitment to the project and procurement model.

Participants have a perception of significant variations in these factors between the various jurisdictions and projects within a jurisdiction.

The degree of commitment to the PPP procurement process and expertise of Government project teams directly impacts decision-making efficiency and the overall timeframes taken to complete procurement processes.

Specific issues that Participants raised in relation to inefficiencies in the procurement process that can occur included:

• excessive information and documentation requests (almost all Participants mentioned this issue)

• inconsistency in tender documentation (a majority)

• inefficient decision making processes and delayed communication of decisions to market (a majority)

• inefficient resourcing associated with the stop/start nature of the Australian PPP market, due to a number of factors including a lack of pipeline, delayed communication of decisions and protracted procurement processes (a majority).

These factors are far from universal, but have applied for some projects.

Do you have suggested improvements as to the structure of the typical Australian PPP procurement process, including potential precedent processes employed in international jurisdictions?

Although almost all Participants are typically happy with the standard EOI and RFP structure that is used in Australian PPP procurement processes, all indicated a preference to move quickly to a preferred bidder and not to have further bid stages.

Several Participants suggested modifying the RFP approach to include the staged submission of information to Government, as used in some international jurisdictions such as Canada, to facilitate more efficient evaluation processes. Such processes typically require the early submission of technical information, with the commencement of evaluation of commercial solutions and proposed project financing prior to the receipt of final pricing. However, others suggested that this modification would not increase efficiency, due to bidders often altering their technical solution significantly following pricing and presentation of the solution to sponsor committees, particularly in projects containing high levels of design innovation. Consequently, such a modification is not appropriate in Australia.

Further to the above, given current global capital constraints for PPP projects, several Participants suggested the short-term introduction of debt competitions, following the selection of a preferred bidder.

Please provide your views on the overall timeframes typically associated with the procurement process from release of EOI documentation to the achievement of contractual and financial close. Where you have suggested alternative processes in the question above, please comment on suggested timeframes to best facilitate value for money outcomes.

Almost all Participants indicated that the typical timeframes associated with receipt of EOI and RFP responses are appropriate, being in the order of 4 to 6 weeks and 14 to 26 weeks (depending on the complexity of the project), respectively. However, all indicated that the time taken to make decisions and convey this information to the market is often excessive, resulting in significant inefficiency and higher bid costs. Examples provided included the time taken to:

• confirm whether a PPP delivery model will be used

• announce the shortlist for the RFP process. Consortia often incur significant costs prior to short-listing in preparation for the RFP phase of the project, as they often commence work, set up bid offices, etc., given:

- recent Government practise to announce the shortlist and release the RFP within a short period

- increased competitive pressures

• undertake evaluation and communicate the approach to completing procurement.

In respect of the above issues, almost all Participants indicated a significant variation from best practices between different jurisdictions and projects.

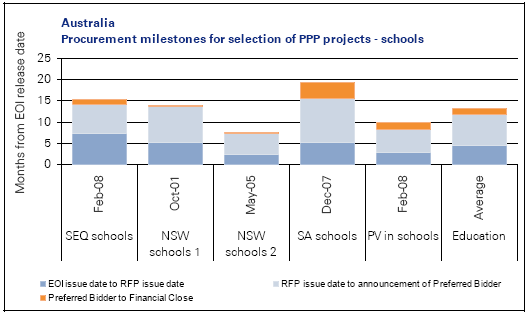

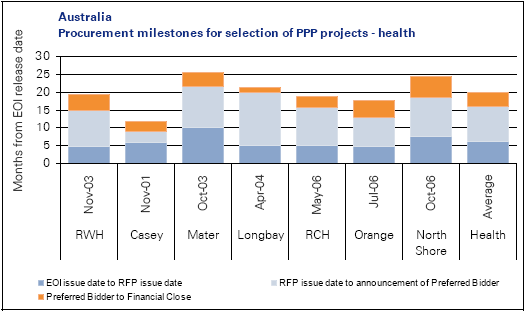

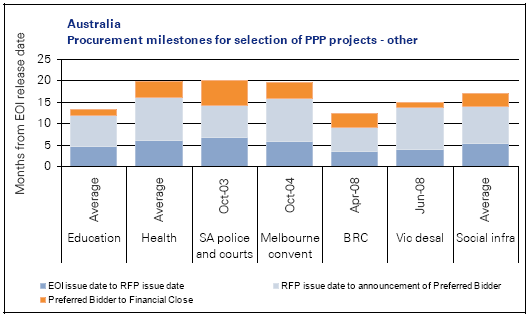

The graph below depicts the procurement timelines for PPP projects closed in Australia, though differences in scope make comparisons between projects in the charts below difficult.

Source: KPMG research

NB The procurement of the SA Schools project was prolonged by an extension of the RFP close date requested by a bidder and by the impact of the Global Financial Crisis.

School PPP projects in Australia have an average procurement period of about 14 months, with some variations between projects (for example, NSW procured its 2nd schools more quickly).

Source: KPMG research

Health PPP projects in Australia have a procurement period of about 19 months on average.

Source: KPMG research

The average procurement timeline for social infrastructure projects in Australia is about 14-19 months, with school projects at the lower end and health projects at the higher end.

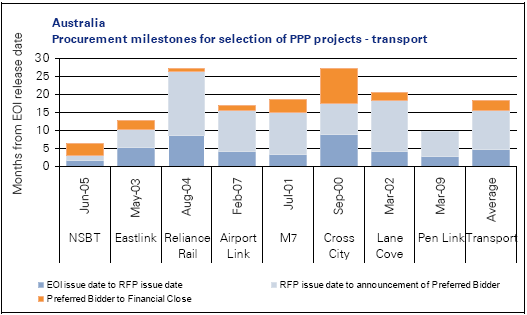

Source: KPMG research

NB Cross City Tunnel financial close was delayed due to the need for a new Environmental Impact Statement resulting from the winning bidder's innovative design

The average procurement timeline for transport infrastructure projects in Australia is 18 months, but with considerable variation about this average.

Are there any significant costs associated with typical EOI processes and, if so, do you have suggestions for potential process improvements?

Almost all Participants indicated that there are not significant direct costs associated with typical EOI processes. However, they suggested that Governments could make improvements in respect of information required, including generic requests for financial statements and information double-up within the various response sections. There was some concern from several Participants at the growing length (and consequent cost) of EOI submissions (noting that the private sector has driven this through competitive tension rather than Government requiring it).

Several Participants mentioned possible confusion as to the purpose of the EOI process and questioned whether Governments should use it as more of a pre-qualification process rather than to encourage bidders to commence early works in advance of receipt of the RFP documentation, noting that, as mentioned above, the pressure for early work comes from the private sector seeking a competitive advantage.

A key issue also raised by several Participants in respect of the EOI process was the general lack of useful feedback received during debrief sessions, whether they were successful or unsuccessful. Feedback often is vague and bland, providing little guide to how Participants might improve future EOI submissions. Unsuccessful parties often want a detailed comparison between their submissions and those of successful parties, with which there are legitimate probity concerns. However, some concrete comparison with the overall standard of successful submissions should be possible.

Please provide details of the order of magnitude of bid costs, post-EOI, for a typical PPP project, including how this might vary for small medium and large-scale projects.

The magnitude of private sector bid costs does vary by project. The table below indicates the level of external bid costs invested by the private sector in bidding for PPP projects in Australia. We have derived these data from information provided by Participants.

Estimated total private sector bid costs (internal and external) | Capital value | Indicative winning bidder's bid costs (up to financial close) | Indicative losing bidders' bid costs (up to preferred bidder) | ||

| A$m | A$m | % of value | A$m | % of value |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Social infrastructure |

| On average | On average | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

$250m project1 | $250 | $2.5-5.0 | 1.00-2.00% | $2.0-3.0 | 0.80-1.20% |

$1bn project1 | $1,000 | $7.0-9.0 | 0.70-0.90% | $5.0-6.0 | 0.50-0.60% |

Economic infrastructure |

|

|

|

|

|

Desalination plant (Vic)2 | $3,500 |

|

| $30.0 | 0.86% |

EastLink (Vic)3 | $2,950 | $20.0 | 0.68% |

|

|

North South Bypass Tunnel (Qld)3 | $2,128 | $27.0 | 1.27% |

|

|

Airport link (Qld)4 | $3,000 | $40.0 | 1.33% |

|

|

Source: 1. Source: Analysis of information obtained by KPMG as part of the consultation process 2. Source: Market comment 3. Source: Presentation by Wal King from Leighton Holdings Limited at the 2009 CEDA conference 4. Source: Presentation by Peter Hicks from Leighton Holdings Limited - Overseeing Queensland's largest PPP project (27 February 2007) | |||||

There appear to be significant differences between individual Proponents' bid costs, which may be due to differing approaches, with some Proponents sub-contracting more work on bids than others, and some managing external advisors more efficiently.

For Australian economic infrastructure projects, the quantum of bid costs is significantly higher than that for social infrastructure projects (partly because of the larger project sizes: bid costs as a percentage of capital value can be lower).

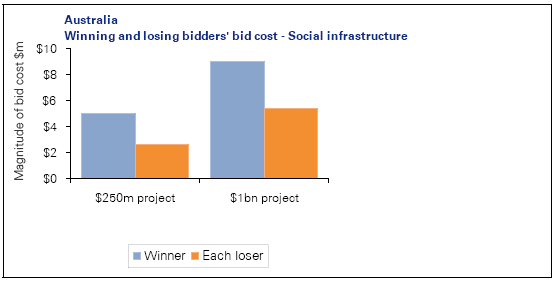

From the above, it is evident that the quantum of bid costs increase as the capital value of the project increases, but not proportionately. Nonetheless, in absolute terms, bidding for PPP projects is expensive: typically $2.5 million "at risk" for projects with a capital value of $250 - 300 million, rising to $5 - 6 million for a $1 billion hospital and $30 million or more for a large $2 billion+ economic infrastructure project.

At financial close, approximately 30% of the winning bidders bid costs relate to internal costs (including salary costs, corporate overheads, etc.) and about 70% to external costs. The internal costs percentage is slightly higher, at about 40%, for the period to preferred bidder. For social infrastructure, the wining bidder incurs approximately 55% of bid costs in the period to preferred bidder (see graph below).

A large part of the difference between the winning and losing bidders costs are success-based fees. Several Participants mentioned high success fees in finance-led bids as a factor driving aggressive bids, particularly for toll road projects.

Source: KPMG research and data obtained during market consultation process

KPMG found EOI submission costs to be insignificant.

Where possible please provide details as to the breakdown of typical bid costs, in particular in relation to design (including relevant components), legal, financial arranging (where appropriate), tax structuring, submission costs and any other key components.

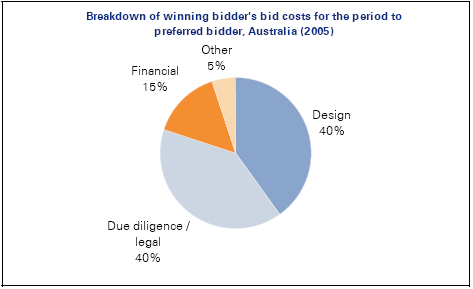

The breakdown of bid costs has changed substantially over time. A (2005) Deloitte report prepared for Partnerships Victoria estimated that, on average, the total bid costs for a project was $5 million (noting that costs varied across projects), with about 70% relating to the period from EOI to announcement of preferred bidder (the EOI submission costs were insignificant), as shown below.

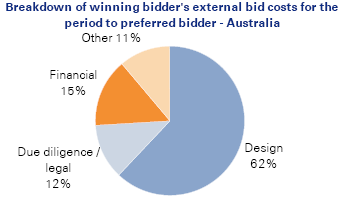

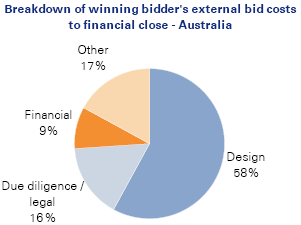

The above graph shows that, in 2005, the design and legal / due diligence components were key drivers of bidding costs (about 40% each). Since then, there has been a marked change in the profile of bid costs. The graphs below show the cost profile of a typical social infrastructure project.

|

Source: KPMG research |

|

Source: KPMG research |

In 2009, design alone is the dominant cost driver (ranging between 50% and 65%, depending on the project). The reduction in legal costs since 2005 may be due to an increase in experience over time as well as the positive impact of published standardised commercial provisions.

Bidders often heavily discount the external bid costs to preferred bidder stage in anticipation of a success component (for example, legal fees to preferred bidder stage are largely success based).

Although design costs are still high for economic infrastructure projects, they are less dominant than for social infrastructure, partly due to more due diligence costs (such as traffic studies).

For the key components identified, please provide detail as to how the process may be improved and indicate where it could achieve savings, including the assumed savings impact.

Most Participants consider that much of the information Governments request as part of the initial bid response is unlikely to be necessary for evaluation purposes, and suspect that it has little influence on the selection of a preferred bidder.

A key component of bid costs is the design element and associated level of detailed technical information required, in particular the level of drawings requested. Participants indicated that the number of drawings typically requested as part of the bid submission is excessive and adds significant cost. Examples provided are the requests within the initial RFP submission for:

• detailed electrical layout drawings, including the location of power points and room data points

• details of signage, including fonts.

Participants indicated that contractors do not require these types of drawings to price the project (using room data sheets instead) and that these layouts require updating each time there is a change to the architectural drawings and functional layouts (which happens frequently).

Although other information (such as construction management plans or operational and maintenance manuals) may not significantly increase total bid costs, Participants indicated that it is time consuming to prepare, generic in nature and may not represent the eventual approach. As a result, Participants consider that they divert the construction and facilities management contractors' focus from development of the technical solution, whilst adding limited value to the development of the overall proposal.

A majority of Participants (excluding pure financiers and operators) indicated that they could make substantial savings in design costs by not having to provide information they regard as being unnecessary for bid evaluation. Participants with experience of the Canadian market cite reduced information requirements, including the level of design detail, as one main reason why bid costs in Canada generally are lower than those in Australia.

In addition, several Participants mentioned the need in some projects to undertake due diligence investigations (such as geotechnical surveys) individually, when all bidders require their results, thus unnecessarily multiplying up total bid costs. However, most project teams are aware of this issue and do procure investigations on behalf of all bidders commonly

Do you consider that the level of information typically requested at EOI is appropriate? If not, please provide detail as to potential improvements.

Although almost all Participants typically consider the level of information requested at EOI appropriate, they suggest that Governments could improve the process from the perspective of minimising multiple requests for similar information throughout the documentation as well as the development of a central repository for generic information, such as the financial statements of regular players within the PPP market.

Several Participants suggested that Governments could provide page limitation guidance for the EOI response, given a general view that the EOI responses are 'getting out of hand'. However, a similar number of Participants indicated that they had a clear preference not to have page limits. It is not clear that there would be any significant advantage gained from imposing page limits.

Which elements of RFP documentation do you consider unnecessary for the initial bid submission? For specific elements identified, please suggest an appropriate time for submission (if applicable) and how Governments can achieve certainty to the extent they have not received information as part of the bid process.

There were a number of areas of RFP bid documentation that Participants identified as contributing unnecessarily towards bid costs (as noted above). These areas included:

• design documentation requests, in particular the number of drawings requested as part of the initial bid submission including elements such as detailed mechanical and electrical drawings and structural drawings (a majority of Participants other than pure financiers and operators mentioned this area)

• communications and stakeholder management plans and related documentation (around half)

• generic project management documentation such as construction management plans, occupational health and safety plans, operational and maintenance manuals, etc. (a majority).

Governments would face relatively little risk by not requiring this information at the RFP stage, as discussed further in section 6.4.

Another area identified by several Participants is the requirement for full legal documentation (as opposed to term sheets) for downstream consortia arrangements (both construction and facilities management contracts) and for debt finance. Although the absence of full documentation could expose Governments to some risk of the winning Proponent not being able to deliver its Proposal without amendment, they could mitigate this risk by requiring strong letters of support from the parties concerned.

Please identify other potential improvements with regard to quality and content of RFP documentation and, in particular, the proposal requirements.

Several Participants indicated the degree of non-specific information requested by Governments as a key issue of concern, citing the tendency to add to information requests for each new project without critically assessing whether information requested on past projects remains appropriate in the current instance.

Do you consider that probity processes can be overly restrictive and prevent the achievement of best value for money outcomes for Government? If so, please suggest process improvements that could increase efficiency whilst maintaining integrity of process and continuing to protect public interest.

Australia is relatively unusual in having formal probity processes and separate probity auditors and advisors. Participants involved in bidding consortia typically indicated no visibility to probity processes except for the requirement to sign up to the Probity and Process Deed (PPD) and the attendance of probity auditors/advisors at workshops as part of the Interactive Tender Process.

Almost all Participants were very positive towards Interactive Tender Processes and increasing levels of interaction on recent projects, and would like to see further increases in interaction in the future. However, Participants feel that the effectiveness of interactions varied from project to project, often depending on the level of experience and capability of the project director and key project team members. In projects where project teams appeared to lack confidence, Participants felt that the Interactive Tender Process failed to result in effective interaction and good outcomes.

Most Participants suggested that the PPD requires re-alignment with the intended objectives of the document. Key concerns raised were the:

• level of indemnities required - it is very difficult to get new and existing players to sign up to them

• inflexibility in changing consortium members, which may result in reduced competition (although there may be genuine probity concerns about major changes)

• tendency to add to the document for each new project without critically assessing whether information requested on past projects remains appropriate in the current instance.

Participants bidding on projects commented on the rigidity of 'non-compliance' criteria included in some procurement documentation, which leave little room for innovation and restricts the ability of Government to consider proposals deemed to be 'non-complying'.

Participants who regularly consult for Government and have much greater visibility in regard to the full procurement process and the influence of probity within it generally had a much stronger view that, for some projects, probity practises have impacted competition negatively and have created process inefficiencies.

Australian probity requirements ensure that, within a relatively complex procurement process, Governments maintain transparency and fairness; and that one bidder does not gain an unfair competitive advantage through an act or omission of the Government. Although many project teams manage probity processes well, there are examples where an overly restrictive view of probity has led to significant inefficiencies.

Please provide details of any other key concerns or issues in relation to the efficiency of Australian PPP processes, including any recommended solutions.

Participants generally felt that debriefing sessions could be improved, as they consider them to be a key opportunity for bidders to learn how to improve their responses and hence their chance of winning future projects, thus leading to enhanced competition and improved outcomes for future projects. Currently, they consider the feedback provided as being too generic and high-level, giving unsuccessful bidders very little direction as to how they can improve their responses. Several Participants mentioned probity concerns as a reason for uninformative debriefing sessions, and felt that such concerns were excessive. Although unsuccessful bidders often want a detailed comparison between their bid and the winning bid, with which Governments have legitimate probity concerns, it is possible to provide reasonably detailed feedback on the evaluation of the bid and its areas of strength and weakness without breaching proper probity principles.

Interestingly, only a few Participants mentioned further standardisation of project contracts as a significant issue, most feeling that the current standard commercial principles and increasing use of documentation precedents are sufficient.