The deal for the establishment of a new museum in Leeds

3 The Armouries decided to proceed in 1990 with the establishment of a new museum as it considered that this would help it to meet its statutory duties by allowing it to put more of its collection on display. The profits from the new museum would also allow it to meet its strategic business objective of becoming more financially self-sufficient by reducing its need for grant-in-aid from the Department (paragraphs 1.9 to 1.11).

4 The agreement the Armouries signed with RAI in December 1993 generally met the specific objectives that the Armouries set for the project. For example, it enabled both the public and private sectors to make a financial contribution to the project and share in its returns. RAI met over £14 million of the £43 million cost of constructing the new museum, with the Armouries contributing £20 million and Leeds City Council and Leeds Development Corporation £8.5 million. While RAI was to retain, in most instances, any profits the museum made, the deal also provided the Armouries and RAI with a share of any future development gain from the redevelopment of the surrounding Clarence Dock site. The Armouries also consider that the deal maximised the private sector's contribution as its financial advisers, Schroders, told it that, in their opinion, the deal with RAI was the best that could have been achieved in the market at the time, given the project's parameters. The competition for the deal, however, elicited little response. Despite the Armouries' marketing of the deal to the private sector, it received only one serious proposal, from RAI (paragraphs 1.17 to 1.24).

5 The deal involved a major transfer of risk to the private sector. RAI was to build the museum in accordance with the Armouries' design and then operate it for 60 years. During the museum's operation RAI would receive no further public funding except for the free provision by the Armouries of its curatorial staff and a contribution by the Armouries to the museum's marketing and promotion costs. RAI was to meet all other operating costs from the income generated at the new museum and retain any profit made. This was a significant commercial risk for RAI as the museum was a new attraction with no proven track record of visits by the public and this was RAI's only source of income. RAI accepted this risk by heavily discounting the projections of visitor numbers and by engaging Gardner Merchant to manage the early launch phase. For its part, the Armouries retained ownership of the collection and full responsibility for its maintenance and preservation (paragraphs 1.25 to 1.31).

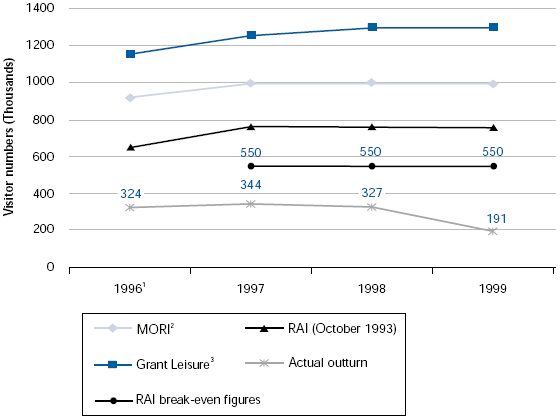

6 The museum was delivered on time in March 1996 and to budget. Once opened it won a number of national and international awards and achieved high levels of visitor satisfaction. However, it also immediately began to incur losses and by early 1999 RAI's cumulative losses were estimated at £10 million. These losses arose as visitor numbers were much less than previously estimated (Figure 2). Delays in the development scheme for the surrounding Clarence Dock site also contributed to RAI's financial problems as these delays, in turn, meant delays in its receipt of its share of the development gains and a lack of passing trade for the museum (paragraphs 1.33, 1.35, and 1.41 to 1.45).

7 In the face of these financial problems, RAI's steps to increase its income and reduce its expenditure resulted in some disagreements with the Armouries over RAI's actions and performance. The early settlement of these disagreements could not be informed by an agreed operating specification which lay down the agreed requirements and standards of performance in operational areas, such as income generation and the maintenance of the museum by RAI. Under the 1993 contract the Armouries and RAI were to agree the specification before the museum opened but in 1994 they agreed to defer this until after the opening as they believed that they would need to acquire some experience of operating the new museum first. In fact the specification was never agreed and the settlement of the disagreements proved more difficult because of the financial difficulties in which RAI found itself and the unpredictability of visitor numbers (paragraphs 1.29 and 1.46 to 1.50).

8 In response to its financial problems RAI undertook two refinancings with the support of both its shareholders and its lenders, the Bank of Scotland. However, as part of the second refinancing in 1998 the Bank said that it would not be able to make additional funding available to RAI after July 1999 if its financial problems persisted (paragraphs 1.52 and 1.54).

9 Both the Armouries' and RAI's ability to deal with the problems at the museum was limited by some of the terms of the 1993 deal. The lack of an agreed performance regime with pre-agreed service standards, monitoring arrangements and provisions for the contract's termination in the event of RAI's poor performance made it difficult for the Armouries to address effectively those areas of RAI's performance, such as income generation and the maintenance of the museum, which were in dispute. However there is no evidence that this had any significant effect on visitor numbers. RAI's ability to cut certain operating overheads was limited and, due to Treasury's stipulations, no additional funding was available to the Armouries to make further contributions to the museum's operating costs beyond those contributions to, for example, marketing and promotion costs agreed as part of the original deal.

2 |

| Visitor numbers | |||

|

| Visitors numbers were much less than expected.

| |||

|

| Notes: | 1. April to December 1996. 2. Excludes school visits and foreign tourists as the estimates are based on a survey of the UK adult population. 3. Includes school visits and foreign tourists. | ||

|

| Source: Royal Armouries | |||

| Because RAI was a private company the Armouries also faced great difficulty in getting timely information on the true extent of RAI's financial difficulties as, under the contract, it had no access to RAI's underlying financial records (paragraphs 1.51 and 1.55 to 1.61). 10 The provisions of the 1993 contract also meant that, in the event of RAI going into receivership, the Armouries could not immediately terminate the contract and take possession of the museum. If it wanted to take over the museum's operation without a period of delay it would have to come to a financial arrangement with RAI's main creditor, the Bank of Scotland. As no attempt was made to negotiate on this basis, it is not clear as to the size of the payment that the Bank would have required. However the size might well have been affected by the fact that, under the terms of RAI's sub-lease of the museum from the Armouries, the buildings could only be used as a museum and had to be kept open to the public at all reasonable times (paragraphs 1.66 to 1.71). 11 The Armouries and the Department considered a number of options for dealing with the financial crisis. The most expensive option was to persist with the 1993 contractual structure with the Armouries funding RAI's continuing losses from increased grant-in-aid. The cheapest options involved the closure or partial closure of the museum after RAI went into receivership. However the Armouries' evaluation of non-financial factors scored these options poorly. The Armouries' preferred option was for it to take over all the museum's operations with RAI remaining in a shell company role, although this would have required the agreement of RAI and its principal lender, the Bank of Scotland. On the basis of advice from the Armouries' legal advisers, the Armouries and the Department considered that, if RAI was to go into receivership, it was unclear whether and to what extent the receiver would keep the museum open, notwithstanding the restrictive covenants in RAI's sub-lease of the museum. If the museum were to close, then the Armouries' compliance with its statutory duties would be adversely affected, as far fewer items of the collection would be on display. The Clarence Dock development scheme would also be adversely affected. Also, if the museum were to close, the Armouries might need extra grant-in-aid either to pay for new accommodation to display the collection elsewhere or to pay off RAI's creditors in order to gain immediate access to the existing buildings. Another important factor was that the political impact of the loss of a national museum, particularly one in the north, would have been considerable (paragraphs 1.70 and 1.74 to 1.81). | ||||

12 Following consultation with the Bank of Scotland, RAI made a late proposal under which the Armouries would take over responsibility for the museum, with RAI providing certain services to the public at the museum. The Department supported these proposals. It considered that this was the only arrangement which was certain to keep the museum open as this was the only option that RAI's bankers would support. It also considered that RAI's proposals offered better value for money; they were marginally cheaper than the option the Armouries preferred, which involved no role for RAI and the Armouries taking over total responsibility for the museum and all the services there, and offered a similar level of non-financial benefits. Finally, the Department preferred these proposals as RAI would retain responsibility for the repayment of its loans with the Bank of Scotland of almost £21 million (paragraphs 1.85 to 1.88).

13 Consequently, in July 1999 the Department told the Armouries that RAI's proposals were the only ones for which the Department was willing to make extra funding available (paragraph 1.89).

14 Under the revised deal reached in July 1999 the Armouries has taken back certain risks which were previously allocated to RAI. The Armouries now operates the museum and meets its operating costs, in the first instance, from the income the museum generates. The Armouries has therefore assumed the demand risk that visitor numbers are insufficient to ensure the museum's future survival. In addition to the income from the museum, the Armouries also receives from the Department extra grant-in-aid of £1 million a year. However this has been insufficient to meet all the extra costs that the Armouries now incurs from running the museum and the Armouries has had to make efficiency savings of almost £2 million a year. In addition the Armouries and Department have identified measures which could help to increase visitor numbers (paragraphs 1.90 to 1.92, and 1.101).

15 RAI has retained responsibility for the provision of catering, car parking and corporate hospitality at the museum. It is possible that it may get enough income from visitors from these activities to ensure, once it has paid off its debt with the Bank of Scotland, that its investors will see some return on their investment. Should, however, RAI go into receivership, the Armouries' position in the new museum is protected (paragraphs 1.93 to 1.94, and 1.97).

16 The revised deal has brought the Armouries benefits. The museum has remained open with a fully trained operational workforce. The revised deal has also ensured the survival of the Clarence Dock development scheme, from which the Armouries will receive a number of benefits such as the free provision of further storage space for its collection. The museum's continued operation retains and, through the Clarence Dock development, creates a number of benefits for the local economy and community (paragraphs 1.107 to 1.110).