The Government saw a PPP as the best way to develop NATS business

1.6 Until the PPP, NATS was owned by the Civil Aviation Authority, which was (and still is) the UK's aviation safety regulator. Successive governments considered the case for separation of responsibility for service provision from regulation and an increased role for the private sector. In 1997 as part of a review by the new Government the Department analysed the implications of its options, ranging from the status quo to full scale privatisation. These are summarised in Figure 4 on page 15.

1.7 The Government rejected the option of a not-for-profit, non-share capital corporation, as pioneered in 1995 by Nav Canada, the provider of air traffic services in Canada. Nav Canada is a private company with no shareholders, financed by borrowing and governed by a Board of Directors with representation from airlines, general aviation, the federal government and employees. It is described in greater detail in Appendix 3. This model was widely cited as an alternative to the PPP during the passage of enabling legislation through Parliament in 2000. The Department worked on the understanding that in the United

2 |

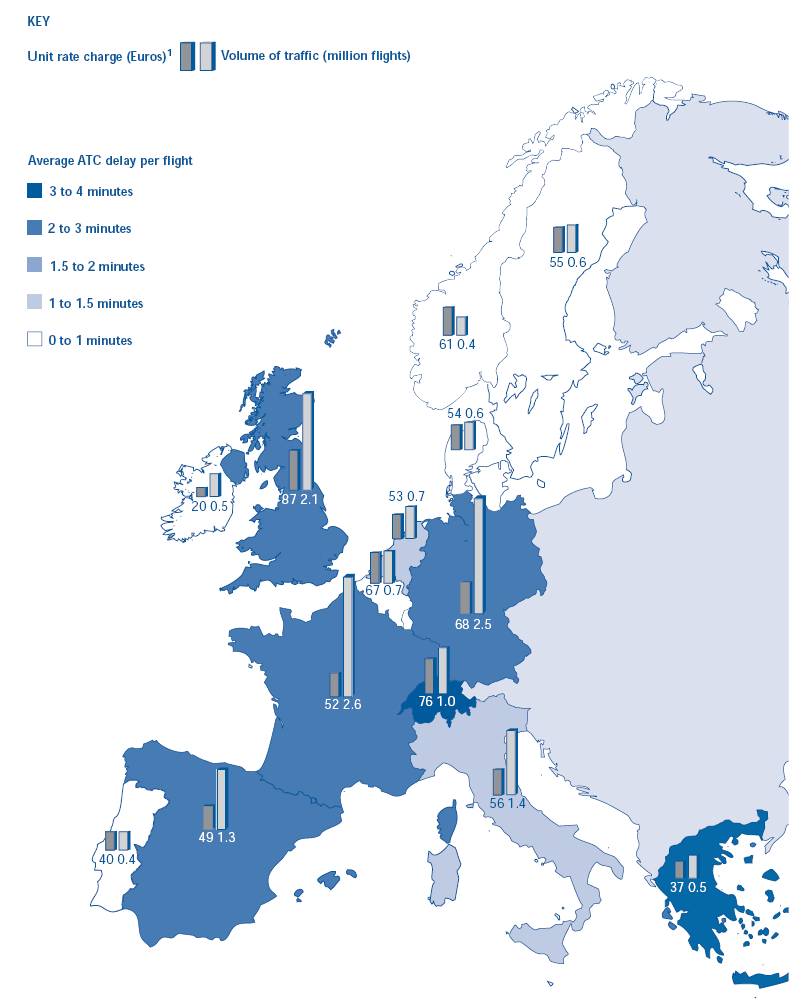

| The European Perspective, 2001 |

|

| NATS' charges were the highest in Europe. It performed better in terms of flight delays, despite managing some of the most heavily used airspace over southeast England.

NOTE 1. The unit rate is the charge in Euros for an aircraft weighing 50 tonnes flying 100km. Source: Eurocontrol Data |

3 |

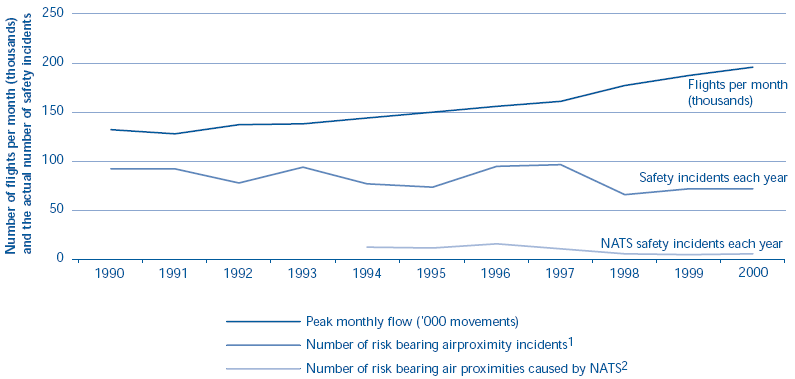

| Key trends in UK airspace since 1990: flights and safety |

|

| Despite sustained growth in the number of flights, NATS' performance has helped to keep down the number of safety incidents.

NOTES 1. Risk bearing air proximity incidents occur when separation between aircraft decreases to such a degree that a risk of collision exists. 2. This information was not available on a consistent basis before 1994. Source: Data from NATS, DTLR and Eurocontro |

Kingdom the particular structure of Nav Canada would not result in NATS' expenditure being classified to the private sector and would not therefore provide the freedom to invest that was required. However, any definitive view would be subject to detailed assessment of the body's control and risk transfer arrangements. The Department were also concerned that without the profit motive or competition the model had neither of the usual spurs to efficiency and might not be well suited to delivery of a major capital programme.

1.8 Since the Department adopted the PPP as the model for NATS, Nav Canada has demonstrated its ability to improve upon the levels of efficiency it achieved under public ownership, and in 2001 won the annual award of the International Air Transport Association for efficient service to airlines. Nav Canada emphasised to us:

■ That inefficiencies are often forgiven in conventional businesses if the business makes a profit.

■ That their five user-nominated directors provide a strong incentive to efficiency.

■ To avoid disputes between rival interests existing employees of airlines or government cannot serve on the Board.

■ Their borrowing is at low cost because they operate an essential service and can recover all costs from customers without referral to an economic regulator. This means that the financial markets rate them as a good credit risk.

In November 2001, Nav Canada put in place an action plan to deal with an estimated $145 million downturn in revenue following September 11th. The plan comprised $85 million in cost reductions, $30 million from drawing on reserves, and $30 million through a 6 per cent increase in charges.

1.9 The Government had the following main criteria for the PPP:

■ that standards of safety and national security should be at least maintained, in particular by separating service provision from safety regulation;

■ to obtain an injection of private sector money and management skills;

■ to develop NATS' business with greater freedom to invest outside normal public sector spending constraints; and

■ that the interests of the taxpayer should be safeguarded.

4 |

| Why the Government elected for a PPP, in preference to other forms of private sector involvement | ||

|

| The Department and Treasury saw a PPP as best addressing their objectives for NATS. Ticks show where they considered that Government objectives would be met.

| ||

|

| Least private involvement |

| More private involvement |

Objectives | The Status Quo | A public company with increased freedoms | Extended use of private finance initiative projects | |

Maintaining and improving safety and national security | Not acceptable, as the government also wished to respond to pressure to separate ownership of NATS from the CAA as safety regulator |

|

There could be safety issues about control of PFI assets within NATS' integrated systems |

|

Securing access to private sector capital investment | NATS would continue under public sector and would therefore have no direct access to private sector capital | Unless the balance of risk was transferred to the spending controls, private sector, NATS would continue under public sector spending controls |

But limited to individual projects for new infrastructure |

|

Securing access to private sector management and expertise | NATS had "bought in" specialist expertise, such as project management, when clearly required. The Government nevertheless considered that there had been shortcomings in NATS' project management | Probably not to a greater extent than before |

But limited to individual projects for new infrastructure |

|

Proving an incentive to efficiency | Weak incentives to invest to improve operational performance | This would be a clearer framework, with targets set by government as a shareholder | Less incentive on the private sector than through a PPP |

|

Accountability to users | Users had no direct say in the way the business was run, although NATS did consult them | This would depend on the terms of the company's charter, negotiated with stakeholders | Unchanged (Enhanced arrangements to consult users would be set in place, in particular through a Stakeholder Council) |

|

Providing freedom to invest and do business overseas | NATS had a consultancy business operating overseas, but there were weak incentives to invest overseas. In any case, tight public sector spending constraints meant that there was little chance of necessary financing | Overseas consultancy would continue, though constraints on foreign investment were likely | Unchanged |

|

Providing a return to the taxpayer | No sale proceeds | No sale proceeds | No sale proceeds |

(Proceeds from 46% sale and future dividends) |

|

| Greatest private sector involvement |

|

Objective | A not-for-profit non-share corporation, as in Canada Paragraphs 1.7 -1.8 refer) | A fully privatised company, contracted to the CAA, shares sold by flotation |

Maintaining and improving safety and national security |

|

In the absence of any Government controls within the company, tight external control would be needed to ensure safety and national security. |

Securing access to private sector capital | The Department thought it would be difficult to ensure that NavCanada's particular structure would be classified as in the private sector and so avoid inclusion in public sector borrowing in the UK. |

|

Securing access to private sector management | At that time, government doubted that this model would bring in new management |

|

Proving an incentive to efficiency | Government doubted that this model would incentivise efficiency as strongly as the PPP |

Though a company may not bring in new management as quickly as in a PPP. Efficiency would also depend on effective regulation and contract management by the CAA |

Ensure accountability to users |

| Users were not keen on this model, which would give the CAA the dual role of NATS' regulator and consumer. |

Provides freedom to invest and do business overseas | Government considered that overseas activities would be constrained |

|

Providing a return to the taxpayer |

(Proceeds from 100% sale) |

Though a flotation may not be as attractive to investors as a sale to a single trade buyer. |

Sources: Assessments of options by NATS and the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions, 1997 | ||

Figure 5 shows how these criteria were translated into detailed objectives for the PPP. The Department and the Treasury attached importance to the potential proceeds from a sale. Some £500 million in receipts had been assumed in the Department's expenditure totals inherited from the previous administration. In June 1998 the Government announced its decision to adopt a PPP in which a private sector partner would acquire operational control of the business, and take 46 per cent of the shares of NATS. The structure of the PPP is summarised at Figure 6.