But there are particular risks to NATS' ability to finance itself

The PPP was set up with a tight financial structure

3.18 On completion of the PPP deal on 27 July 2001, the Airline Group provided £795 million of funds, from its own resources and from a loan taken out with a consortium led by four main banks. They used this to acquire NATS and meet associated transaction costs, leaving £3.5 million of cash in the business (see Figure 20).

20 |

| NATS' indebtedness has increased as a result of the deal | |

|

| To finance the PPP deal, NATS' indebtedness rose from £330m to £733m. | |

|

| Source of funds | £ million |

|

| Cash from the seven Airline Group shareholders | 50.0 |

|

| Strategic Partner shareholder loan, from British Airways1 | 15.0 |

|

| Capital from strategic partner | 65.0 |

|

| Cash in NATS at completion | 3.5 |

|

| Bank Loans for the acquisition, repayable by NATS2 | 733.0 |

|

| Less hedging costs | -7.0 |

|

| Total available funds | 794.5 |

|

| Uses of funds |

|

|

| Equity purchase from government | 65.0 |

|

| Repayment of NATS' existing National Loan Fund debts | 330.0 |

|

| Purchase of stake in NATS from Government | 370.0 |

|

| Hedging costs | -7.0 |

|

| Government's immediate cash proceeds | 758.0 |

|

| Banking costs | 33.0 |

|

| Cash left in NATS | 3.5 |

|

| Total funds used | 794.5 |

|

| NOTES 1. British Airways provided further funds after the Airline Group announced that it could not finance the acquisition on the terms it originally offered, (Part 1). 2. NATS is required to meet the cost of servicing these loans, arranged by Abbey National, Bank of America, Halifax Bank of Scotland and Barclays, over a 20 year period. Source: National Audit Office | |

3.19 The strong competition between the final two bidders had driven the sale proceeds up to the limit of what they considered the business could sustain, based on their assumptions about growth in traffic and the need for further investment. In addition, the regulatory regime required NATS to reduce the level of its charges. NATS had long needed to borrow to meet its investment needs, but as a result of the acquisition, the level of debt within NATS rose from £330 million to £733 million (compared to its regulatory asset base of £632 million in 2000/2001 prices). Debt would rise further over the next twenty years as the Company would draw on a further £715 million of loans to invest in new air traffic control capacity.

3.20 The head of the Economic Regulation Group in the Civil Aviation Authority expressed to us his concerns over NATS' indebtedness. In particular, he noted that NATS' debts are now greater than its £632 million regulatory asset base, the value of assets on which the regulator allows it to make a return when setting its prices. There are various ways in which the company can find financial headroom to mitigate this problem, for example its income may grow, or its costs may be cut, more quickly than the regulator predicted when setting prices. But even with these factors, the Regulator has questioned whether NATS' indebtedness is likely to be sustainable.

3.21 Whilst recognising the Regulator's perspective, the Department and their advisers assessed the indebtedness of NATS under the Airline Group's proposals in different terms, specifically whether the business would have sufficient cash flow to meet its debt obligations.

3.22 In order to match loan payments with expected growth in NATS' income, the debt arranging banks adopted a debt repayment profile which loaded debt repayments into the latter years of the loan. Such customised profiles are normally used to reduce debt repayments during periods of heavy investment and ensure sufficient cash flow in the business to cover the loan. Deferral of repayments also increases the total amount of interest payable by borrowers. For NATS to meet its debt service obligations, continued growth of the business will be essential. The necessity to expand the business in order to cover rising debt makes NATS' finances vulnerable to downturns in the volume of traffic.

3.23 The Department and their advisers required Nimbus and the Airline Group to demonstrate the strength of their financial proposals against a range of uncertainties. These nine mandatory scenarios tested were mainly for the risks that capital expenditure and staff costs would be higher than expected. One scenario dealt with adverse variations in traffic; specifically the risk that annual growth in business would be only 3.5 per cent as opposed to the 6.7 per cent each year in the baseline assumption. In the case of the Airline Group, the result of these mandatory tests was that NATS would have enough cash to fund its debts. Margins were however acknowledged to be tight, with NATS' available cash estimated to be between 1.2 and 1.5 times the debt payments.

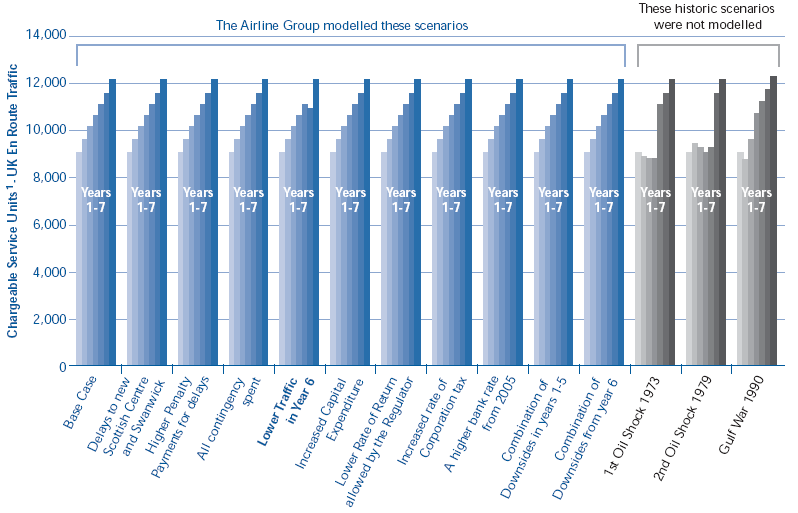

3.24 In addition to these mandatory tests, the Department and their advisers requested sight of any further sensitivity tests that had been run on the bidders' financial models at the request of the Group's lender banks. The Airline Group produced ten such further scenarios, only one of which considered lower than expected traffic volumes, a slight fall in UK traffic only in year six of the Partnership (see Figure 21). It allowed for no drop in the number and average size of aircraft crossing the North Atlantic, from which NATS normally derives around 45 per cent of its en route traffic revenues. Nevertheless even the scenario allowing for a fall in traffic in year six produced tight debt service cover ratios after the first five years of the Partnership, when increased capital investment by NATS would coincide with temporary cessation of growth in traffic, (Figure 22). Even this short-term halt in the rise of traffic would have brought NATS close to, but not quite into, a position of not having enough cash to service its loans.

3.25 We consider that other scenarios could usefully have been tested, such as a lower traffic case, given the risks of growing economic recession in the USA and uncertainty as to whether airports could cope with four to six per cent annual growth in perpetuity. The economic regulator can adjust for such factors every five years when capping NATS' prices, but in the meantime NATS may encounter financial difficulties.

21 |

| Testing the Airline Group bid against different scenarios |

|

| The Airline Group modelled a range of scenarios to demonstrate the financial robustness of their bid. None of them included a severe and protracted hiatus in traffic growth to the extent seen in previous decades.

NOTE 1. The Chargeable Service Unite is the basis on which European air traffic providers charge airlines for their services, It represents an aircraft of 50 tonnes flying 100km. Source: National Audit Office |

22 |

| Covering NATS' debt | ||||

|

| Testing of the Airline Group's bid predicted that NATS should have easily enough cash to cover its payments on its debts in the first five years, but that margins would be very tight afterwards as investment peaked. The banks required that the cover ratio should not dip below 1.1 over the duration of the loan. | ||||

|

| Cases that were used to test the Airline Group bid in July 2001 | Peak debt (£m) | Minimum debt cover in years 1-51 | Minimum/ average debt cover from year 6 on2 | Minimum loan life cover ratio3 |

|

| Base Case | 1,281 | 2.33 | 1.30/1.61 | 1.26 |

|

| 1. Delays to major projects | 1,271 | 2.31 | 1.27/1.52 | 1.24 |

|

| 2. Higher penalty payments for delays | 1,286 | 2.32 | 1.26/1.53 | 1.25 |

|

| 3. NATS spends all its contingency | 1,344 | 2.35 | 1.19/1.48 | 1.25 |

|

| 4. Temporary halt in traffic growth in year 6 (paragraph 3.24) | 1,294 | 2.34 | 1.10/1.40 | 1.21 |

|

| 5. Capital spending up 10% | 1,294 | 2.34 | 1.23/1.53 | 1.25 |

|

| 6. Regulator allows lower return when setting NATS' prices | 1,281 | 2.33 | 1.13/1.41 | 1.21 |

|

| 7. Corporation tax rises to 35 per cent | 1,287 | 2.32 | 1.19/1.52 | 1.23 |

|

| 8. Higher bank rate | 1,297 | 2.33 | 1.12/1.40 | 1.22 |

|

| 9. A combination of downsides in years 1-5 | 1,242 | 2.27 | 1.04/1.38 | 1.21 |

|

| 10. A combination of downsides in years 6 on | 1,357 | 2.29 | 1.02/1.36 | 1.20 |

|

| NOTES 1. This ratio measures the extent to which the business' net revenues are sufficient to cover the debt. A ratio of 1.1 would mean that NATS was forecast to have £1.10p for each £1 that it must pay in debt interest and repayments. If NATS' forecasts fell below this ratio, it would be in breach of its loan terms, and could not draw down more lending. 2. The expected cover ratios will be much tighter from year five onwards because this is when NATS intends to draw on most of its loans for investment purposes. 3. This measures the ratio between the net present value of projected revenues for the rest of the loan and the outstanding amount of the loan. Source: National Audit Office analysis of Airline Group Financial Model. | ||||

3.26 The events of September 11th resulted in a dramatic downturn in NATS' North Atlantic traffic. This has resulted in NATS slipping into financial distress. It was of course impossible to foresee the September 11th attack as the trigger for a downturn in air traffic volumes. Nevertheless there have been two significant downturns in air traffic over the last 30 years. In order to identify the effects of more serious traffic downturns on NATS' business we analysed the three key periods in the last 30 years during which the pattern of growth in air traffic has been interrupted, inputting these variations into the Airline Group's financial model for NATS3. These periods were:

■ the first Oil Shock, starting in 1973;

■ the second Oil Shock, starting in 1979; and

■ the Gulf War 1990.

3.27 Figure 21 also shows the effects of these historic downturns on NATS' traffic volumes. During the Gulf War, the increase in military activity across the North Atlantic counterbalanced NATS' downturn in civil aviation, and we found that NATS finances may have dealt with such pressure. Conversely, given a reduction in traffic on the scale experienced in both of the oil shocks, each of which lasted several years, we found that NATS would have been unable to meet its debt service obligations.

3.28 We discussed with the Department's lead financial advisers, CSFB, the implications of a less tight financial structure for NATS. We asked them whether the Department could have placed restrictions on the structure that bidders could have proposed, for example by requiring a minimum level of cash reserves to be kept in NATS, or by placing a maximum limit on the indebtedness of the company. CSFB considered that it would have been unwise for the Department to have mandated a particular financial structure for NATS. They had found little appetite amongst investors to provide more equity for NATS, so if the government had required high reserves to be kept in the company, this would have fed, pound for pound, into lower sale proceeds for the taxpayer. CSFB regarded this as an inefficient way of protecting the company from the risk of financial stress. It was better for the shareholders to respond to the company's needs as risks transpired. Also, a more cautious financial structure might still have been tested by the effects of the aftermath of September 11th on NATS' revenue and plans.

___________________________________________________________________

3 We have used the data that was available over this full period, showing the number of flights handled by NATS. In a downturn NATS tends to experience a disproportionate reduction in revenue owing to fewer large transatlantic aircraft flying long distances across the UK. Therefore the number of flights may understate the full effects on NATS' revenues.

- NATS faces new risks in financing its business plans

- NATS is constrained in its ability to increase its revenue

- NATS' plans for developing its unregulated business are not yet clear

- NATS has a high base of fixed costs, and cuts will be challenging to achieve

- There are difficulties in seeking additional external finance