The new Local Education Partnership (LEP) model

3.13 Local Authorities are responsible for choosing their procurement model. PfS will not recommend that projects are funded, however, unless they use a LEP or can demonstrate that their alternative provides value for money. By December 2008, 15 Local Authorities had established a LEP, four established their own framework, two use a national framework for design and build projects set up by PfS (paragraph 3.21), one through separate design and build contracts, and two used a single PFI deal. PfS expects most to use LEPs in future.

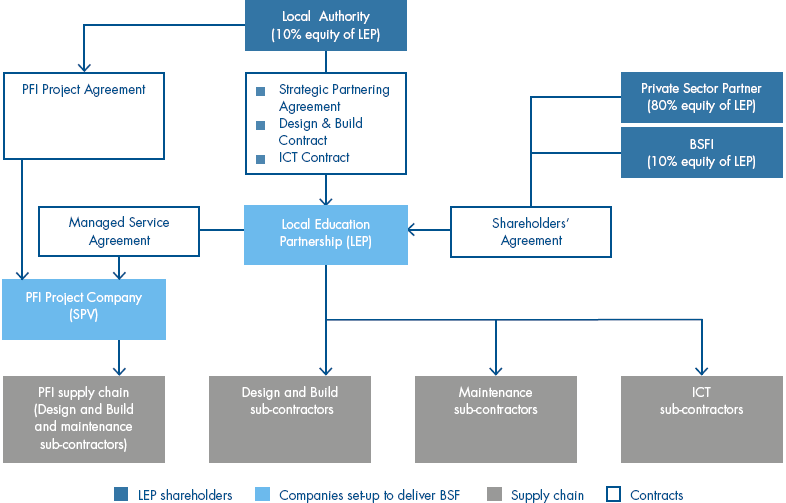

3.14 A LEP is a joint venture company that manages the scoping and integration of services to deliver new and refurbished capital works. Figure 15 shows the contractual framework that parties sign up to when a LEP is established. The strategic partnering agreement grants exclusive rights to the LEP to deliver projects for a fixed period, likely to be 10 years, subject to value for money tests. The Local Authority then contracts a LEP to refurbish schools through traditional Design and Build contracts and also ICT services. A PFI Project Company is contracted directly by the Local Authority to build new schools and is managed by the LEP through a managed service agreement. The school building, ICT services and ongoing maintenance of these assets are sub-contracted by the LEP and PFI project companies to a private sector partner, which is typically the consortium of supply chain and finance companies that includes the private investors in the LEP and PFI project company.

3.15 The LEP Board is governed by four private sector partner directors, a Local Authority director and a BSFI director. The Local Authority director is typically a representative from the Senior Management Board, such as the Chief Executive, Finance Director or other Corporate Directors. The Board is chaired either by an independent chair or one of the LEP Board Directors, whose vote does not become casting.

3.16 A LEP is intended to provide a number of benefits:

i Partnering efficiencies through its ten-year framework and large flow of work. This creates incentives for better joint working. There is some early evidence of quicker delivery of subsequent projects and savings in transaction costs (paragraph 3.29). As work is not competitively tendered, benchmarking and incentives are used to put pressure on capital costs.

ii Development resources, by involving the private sector early on in the development of projects, which helps in scoping more viable projects. The LEP also shares the costs and risks of scoping project, which provides an incentive to manage the costs better.

iii An integrated supply chain with the ability to supply all BSF services under one umbrella contract, allowing PFI, conventional design and build, facilities management and ICT contracts to be combined under a single interface with the Local Authority, schools and other stakeholders.

iv A strong permanent local business with the delivery capacity for BSF and the Local Authority's other capital programmes. The LEP should have specialists in education and understand the Local Authority's education priorities. The Department also wants LEPs to join up programmes, have a local base and links into the local community, and to act strategically and entrepreneurially to deliver the Local Authority's needs.

v Stronger educational and community links through increased incentives and processes for the private sector partner to contribute to wider social and educational aims of the programme. The contribution to wider educational aims is used by the Local Authority when assessing the performance of the LEP. Such contributions include for example providing apprenticeships and mentoring of local pupils.

3.17 Bidders develop the first few school designs during the initial competition. The Local Authority then selects a partner based partly on its performance in designing the first projects. Schools and Local Authorities have, however, identified some drawbacks.

i Despite knowing the Local Authority's budget, bidders tend to raise the expectations of the schools and Local Authorities in the early stages of procurement, leading to later de-scoping of the designs to keep them within budget.

ii The best design of each individual school developed by bidders during the procurement process does not always win, because: the Local Authority scores bids on a variety of factors of which design counts for only 18 per cent (Figure 16 overleaf); the assessment of a bidder's design capability is based on the aggregate assessment of all the bidder's sample schemes; and authorities cannot choose good designs from a losing bidder.

iii It is difficult for schools and Local Authorities to collaborate properly with the designers because they have to work with each of the competing bidders, and have to be careful not to communicate ideas between bidders.

15 | The contractual structure of the LEP |

|

|

Source: Partnerships for schools contract guidance | |

3.18 It would be possible to select a private sector partner and set up a LEP before designing and scoping the first schools. This sequence would potentially be cheaper and quicker to procure, especially if the private sector partner was taken from a national framework, because only one set of designs would be needed. But it would also mean that Local Authorities could not use the experience of scoping the first projects in assessing bids and the first projects would not establish a local benchmark of costs in competition. PfS believes it needs more confidence on whether such an approach would comply with EU regulations.

3.19 Once a LEP is established, projects are developed without re-tendering, with the risk that prices charged by the LEP will be uneconomic. This risk is mitigated by controls within the LEP contract arrangements, including:

16 | Selection criteria used by Local Authority to select a Private Sector Partner, set out in the standard tendering documentation | ||

|

|

|

|

Criterion | Weighting | % | |

The LEP Partnership |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Overview of LEP & Delivery of Partnering Services | 10 |

| |

Value for Money, Performance Monitoring and Continuous Improvement | 12 |

| |

LEP Business Plan, Supply Chain Management and Interface Issues | 12 |

| |

Design Philosophy | 6 |

| |

Sub-total for LEP Partnership |

| 40 | |

Sample Schools |

|

| |

Design of Sample Schools | 12 |

| |

18 |

| ||

Sub-total for Sample Schools |

| 30 | |

| 20 | ||

Financial |

| 5 | |

Legal |

| 5 | |

TOTAL |

| 100 | |

Source: PFS standard tender templates |

|

| |

NOTE Design is assessed as the sum total of design philosophy (6 per cent) and on the design of sample schools (12 per cent). | |||

i inclusion in the initial competition to establish the LEP of at least two projects that are used to set local cost benchmarks;

ii PfS benchmarking data at a national level, which can be used by Local Authorities to assess each project developed by the LEP;

iii competition within the supply chain underneath the LEP, especially where the private sector partner is not itself part of the supply chain;

iv contractual provisions to share economies of scale and learning curve efficiencies, by guaranteeing reduced real prices for each subsequent project;

v contractual provisions to market test some of the new projects and services provided by sub- contractors to the LEP;

vi performance monitoring of the LEP and the threat of terminating its exclusivity if the projects it develops are not value for money;

vii public sector directors on the LEP boards to promote transparency in the scoping of projects; and

viii standard form contracts agreed at the beginning so each project is developed on a consistent basis.

3.20 Having an integrated supply chain is a key part of a LEP's ability to promote long-term partnering. To achieve these benefits, however, governance and management structures must give management adequate control over the business. Local Authorities must also be able to create a credible threat that they might terminate the guarantee of future work. The contracts should also provide for (i) transparent information from the supply chain; (ii) the ability for the public sector to withhold payment if the supply chain cannot produce reliable information; and (iii) incentive mechanisms for each supply chain contractor aligned with the public sector client. The LEP structure is designed to address these issues.

■ The public sector shareholding and the associated representation on the LEP Board provides some insight into contracts and costs with the main suppliers.

■ Fixed price contracts are established for each project, with standard payment terms that withhold payments for non-delivery or under-performance.

■ The Local Authority has the ability to terminate the guarantee that it will use the LEP for all its major school projects if the LEP does not perform to its obligations under the Strategic Partnering Agreement.

3.21 The main alternative to a LEP is to procure each project through a framework agreement. Under a framework agreement, a small number of contractors agree to standard terms and conditions and can compete for each project. PfS has set up a national framework for design and build projects, which Local Authorities can use. Alternatively, Local Authorities could set up their own frameworks, as Manchester City Council has done (see the Manchester case study in the case study annex). Frameworks are generally much cheaper and quicker to establish than a LEP, but:

■ only last four years by EU regulations;

■ are less flexible in what can be included because there can be no negotiation between the Local Authority and contractors during tendering; and

■ separate frameworks have to be procured to deliver Design and Build, ICT and Facilities Maintenance services.

3.22 It is also possible to procure schools through a single PFI contract without a LEP. The steps to set up a PFI contract are very similar to those to establish a LEP, but new projects would have to go out to tender. It may therefore be appropriate where the Local Authority wishes to use PFI but there are too few projects to develop a flow for the LEP, such as in Solihull (see the Solihull case study in the case study annex).