Achieving value for money in the long term

3.28 LEPs should provide procurement cost savings where the Local Authority is using private finance or lots of different types of contracts, and has a sustained flow of work that cannot be commissioned and developed in one go. Specific costs savings should arise from:

■ procurement cost savings, from not having to re- tender new projects;

■ quicker scoping and design of new projects, from having incentives and governance arrangements which share scoping costs and provide transparency over them; and

■ partnering efficiencies, from Local Authorities and their partners developing a better understanding of how to work with each other during the 10-year partnership.

3.29 The early evidence shows that developing projects through a LEP is quicker, cheaper and more efficient than re-tendering the work. A lack of planning on how LEPs would work in practice has, however, led to delays in the first projects developed through the LEP and difficulties in establishing effective partnering from the start. As at December 2008, only Leeds and Lancashire had finished scoping school projects through the LEP. After a year's delay in starting (see the Lancashire case study in the case study annex), Lancashire has developed two single school PFI projects through the LEP, the first taking 12 months and the second 7 months, less than half the time it normally takes to establish a PFI contract (see paragraph 2.12). Leeds used its LEP to develop a separate £33 million PFI project for two leisure centres in 14 months, six months quicker than Leeds' previous experience of procuring similar sized PFI contracts. Using the LEP eliminated the need for two stages of the standard procurement process, establishing internal project teams and establishing the strategic business case, which saved £200,000.

3.30 We found that none of our case studies with operational LEPs displayed strong partnering behaviour. In one case, the Local Authority was emphasising contractual management at the expense of relationship management. Both sides complained about the other's lack of understanding. In another, the Local Authority was in disagreement with the ICT contractor over the introduction of new software to the schools and the LEP did not mediate.

3.31 We visited a further three Local Authorities and their LEPs in late 2008 to see if they had managed to overcome some of these early problems. Two of these three had experienced delay, but all were working through these issues and were optimistic that they would be quicker in future (Figure 18).

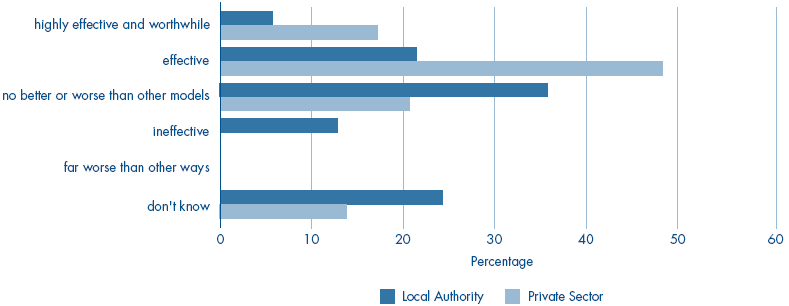

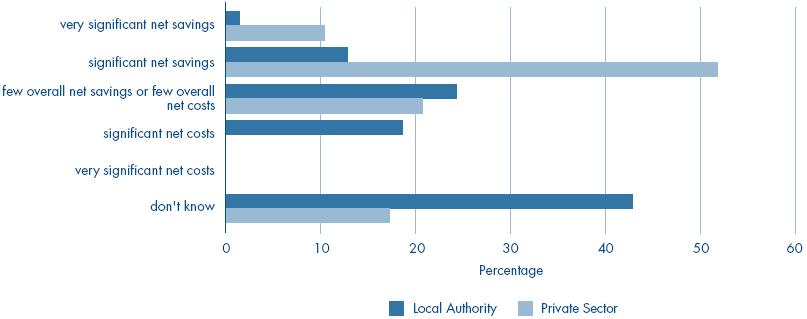

3.32 We found, through our case studies and census of all Local Authority BSF project managers, that most Local Authorities thought it was too early to tell if the expected benefits of the LEP (set out in paragraph 3.16) will be realised. Only 14 per cent of Local Authority BSF managers believe the LEP will produce savings, less than those who think it will add to costs (Figure 19 overleaf). Many did not know. Private sector partners are more favourable to the LEP. Nearly two thirds of the private sector partners questioned in our survey believe the LEP will produce savings.

3.33 We also found that some Local Authorities were not seeking to achieve the full range of intended benefits of the LEP:

i They generally do not pay the LEP to provide the full range of potential services and be an independent "permanent business". They are normally dependent upon their main contractors to provide the services.

ii A few seek to work directly with the lead contractors in a conventional client-contractor relationship. They procure and pay for a LEP, but do not use it to help manage the contractors.

3.34 A few Local Authorities told us that they felt forced into adopting a LEP against their own judgement of what produced the most value for money. The Department and PfS believe that Local Authorities who felt pressured into adopting a LEP approach did not produce a robust business case for not using a LEP and attach weight to the economies of scale of adopting a consistent approach across the programme. It is important, however, that they get buy in at local level or the chances of success are reduced.

|

18 |

Visits to Local Authorities with early problems with operational LEPs |

|

Sheffield (LEP established July 2007) The establishment of Sheffield's LEP led to some tension between the Local Authority and the private sector partner, Paradigm (led by Taylor Woodrow). During the closing stages of the negotiation process, Paradigm had assumed that the Local Authority would be ready to specify the next set of projects so the LEP could start to scope the projects straight away. It became apparent in the run up to agreeing the contracts that the Local Authority was not in a position to release the projects to the LEP as the specification process and stakeholder consultation were still under way, with knock-on consequences for the project flow and working capital of the LEP. Sheffield and Paradigm used this period before subsequent projects were released to develop working relationships, processes and responsibilities for each aspect of the scoping process. This five month pause provided them with a much more detailed understanding of how they would work together than set out in the contracts. They are now developing the next phase of projects and say that they are working very effectively together and more so than if they had gone straight into developing the new projects. For example, Sheffield is submitting more effective town planning applications through the pooling of expertise. Westminster (LEP established April 2008) Westminster was initially not keen on establishing a LEP. Westminster is using only design and build contracts and the benefit of using a LEP is therefore marginal compared to using a framework. This initial reluctance on the part of the Local Authority led to tension during the procurement process. But the Private Sector Partner chosen, Bouygues, learnt lessons from its experience in Waltham Forest, while changes in Westminster's executive team led to a new approach towards the LEP. Both sides have embraced the LEP as a useful vehicle and governance structure, including using the Strategic Partnership Board to bring in all the school sponsors. Westminster is attempting to maximise the value it can get out the LEP by putting additional work through it, including a potential project for a new Adult Learning centre. Waltham forest (LEP established August 2009) Waltham Forest's LEP has had particular problems with its working capital caused by interruption to the flow of projects. This hiatus led to strains in the relationship over the issue of the LEP's viability as a business. Partnership workshops have helped Waltham Forest and its private sector partner, Bouygues, to work better with one another. They agreed that the LEP needed to be more strategic and to appoint an independent chair. They have developed a new stage in the process to ensure the Local Authority agrees a specification and is ready to commission a new project before the LEP starts scoping, which BSFI has disseminated to the other LEPs. Both sides say the relationship has transformed over the six months to October 2008. They foresee the next projects being developed much more quickly. Source: National Audit Office interviews with senior Local Authority managers and their contractors. |

|

3.35 Two Local Authorities, Lambeth and Liverpool, initially used individual design and build contracts for each of the schools in their first wave of BSF. They both propose to run a procurement process to establish a LEP for their next waves of funding. Lambeth believes the LEP will assist with the integration of ICT and Facilities Management services with its design and build contracts.

3.36 Complex governance and contractual arrangements require early attention on how to manage the operational phase. PfS and BSFI are beginning to focus on making LEPs work better. In 2008 they commissioned PwC to review operational LEPs. They started to introduce partnering workshops, to help LEP partners work out the things they needed to do to work better together. They have also increased the amount of time PfS staff are able to spend with each operational LEP.

|

19 |

Local views on the effectiveness of the LEP model |

|

Question: "On the whole, do you believe that having a Local Education Partnership is a good approach to renewing your school estate and equipping it to be capable of improving educational outcomes?" The LEP model is:

Question: "In your opinion, is the Local Education Partnership model likely to bring overall savings or costs to the Local Authority over the ten year exclusivity period (when compared to other ways of procuring school buildings and refurbishments)?"

Source: Survey of local authority BSF managers and their contractors |

|