Appetite for project risk

32. There is very little capacity in the sterling market for unrated or non-investment grade rated bonds. It is, therefore, necessary to obtain a credit rating to issue a large amount of fixed rate debt. Figure 30 above illustrates how little non-rated or non-investment grade debt is issued in sterling. (Indeed, most of this is categorised as "High Yield" debt and is generally placed into a separate class of specialist investors.)

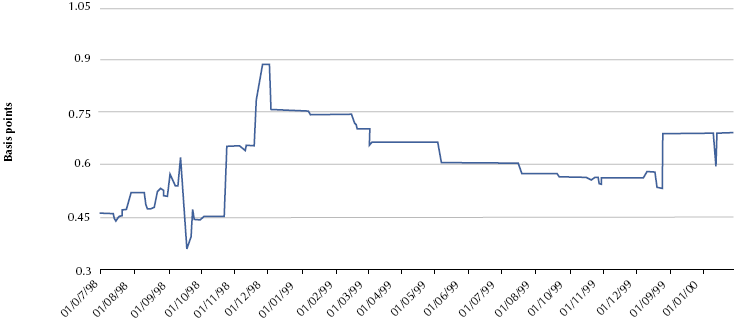

33. Project finance is still a novel concept in the sterling bond market and investors are highly reliant on credit rating. Their sensitivity is such that, in sterling, there is currently a preference to buy project finance bonds which have been insured by a specialist credit insurer ("Monoline Insurer") and carry a AAA guarantee. This is the case even if the underlying project has a reasonable investment grade credit rating. Figure 32 below illustrates that investors may demand a margin of some 70 basis points additional return for an A-rated project. At the time LCR launched its bonds this yield difference was wider.

32 |

| Credit margins of un-enhanced over enhanced bonds |

|

|

|

|

| Source: RBC Dominion Securities |

34. Given the history of the project, it seems that it was unlikely to achieve an investment grade rating without a substantial injection of equity and support from creditworthy sponsors or Government.

35. Some of the prime areas where the rating agencies would have been nervous would be:

a) unpredictability of operating cashflow;

b) basis risk. LCR's income would be a mixture of floating rate interest income, fixed/variable rate purchase proceeds from Railtrack, (RPI linked) grants and RPI correlated income from Eurostar UK. Its commitments would not necessarily match;

c) contingency of Section 2 of the Link;

d) repayment of 2010 bonds partly dependent on Railtrack Group plc guarantee. This is unrated but can be assumed to be A-rated (i.e. a notch lower than the regulated utility, Railtrack PLC). This might act as a cap to the rating;

e) rating agencies are sensitive to construction risk in major projects;

f) the nature of any Government support.

36. It seems that the Government was also constrained by a) a need to change the original concession to LCR as little as possible and b) time, as LCR was running out of money. Given the nature of this project and these constraints, we do not believe that it would have been possible to achieve a high enough rating to attract sufficient demand for bonds issued by LCR without substantial Government support.

37. The Government Guarantee, therefore, brought a number of benefits to the funding process:

a) it removed credit risk;

b) it enabled the bonds to carry a low risk weighting;

c) it enabled the bonds to carry explicit AAA/Aaa credit rating;

d) it enabled the bonds to be simply structured without a complex repayment schedule;

e) it enabled a large amount of bonds to be sold at one time, especially in disrupted markets;

f) it allowed longer tenors to be issued.

38. However, the use of the Guarantee could not:

a) turn the issue into a Gilt;

b) remove the illiquidity premium;

c) remove market and performance risk;

d) avoid some consequential activity in the Gilt market.

39. There is a strong argument in favour of the Government guarantee as the only way of issuing the bonds in large volume and in disrupted market conditions. The question is whether the guarantee enabled LCR to issue the bonds on the cheapest possible basis.