Increases in consumers' surplus

6. Consumers' surplus arises where there is a difference between what consumers of a service or product are willing to pay and what they actually pay. So those who would be willing to pay more will benefit from the service by the amount of the difference between what they would be willing to pay and what they actually pay. It is not usually practical for an operator to devise a price structure which would enable it to capture precisely the benefit that each passenger derives from using the service. For example, the information costs the operator would need to incur to devise and implement a pricing structure which discriminated sufficiently to allow this and the practicalities of its implementation would be prohibitive.

7. A certain amount of price discrimination between different groups of passengers is possible, and more can be charged to groups which are less responsive to higher prices. For example, much higher fares are charged for first class than standard class passengers. Although these are effectively different products, as the type of service is different for the two classes, first class travellers are often business travellers who are less responsive to changes in price than leisure travellers. Business travellers are, therefore, often charged at a higher rate than is required to cover the additional costs of the greater level of service they receive.

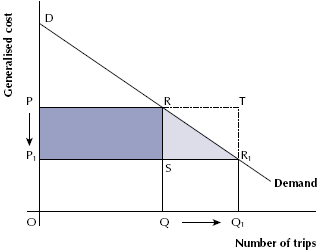

8. The Department estimated changes in consumer surplus for UK resident international passengers. It estimated the benefits due to the increased rail capacity the Link would provide and the benefits due to time savings resulting from faster journey times. The total cost of travel includes money costs, such as fares, but also includes the cost of the time spent travelling, waiting etc. These all form the "generalised cost" of travel. A reduction in journey time reduces the generalised cost of travel and should increase demand, all other things being equal. The expected level of international benefits accruing as a result of the Link were based on a method for calculating consumers' surplus known as the "rule of half". Those passengers who use Eurostar UK before the Link opens get the full value of the capacity and time saving benefits, and those switching to the service only get half of the value (Figure 44). To incorporate the increases in consumers' surplus into the Department's value for money assessments, the annual changes in consumers' surplus compared with the "no Channel Tunnel Rail Link" scenario were discounted at 6 per cent a year after inflation to 1997 over the assessment period. The sum of these annual figures gave the total figure for international and domestic passenger benefits.

44 |

| The Rule of Half |

|

| Before the Link is built, the generalised cost of travel on Eurostar UK (fares plus travel time and other costs) is P and the number of trips made at this level of cost is Q. At this level, the consumer surplus is the area PDR, as those passengers on the demand line would be prepared to incur higher generalised costs to travel, so benefit from having lower costs than they are prepared to pay. After the Link opens, the reduction in journey times and the relief of capacity constraints (thus meaning lower fares) reduce the generalised cost of travel on Eurostar UK to P1. As a result of the lower costs, other things being equal, more passengers will be attracted to travel, so demand increases to Q1. The fall in generalised costs, therefore, increases total consumer surplus to P1R1D. Those who travelled before, OQ, benefit from the full increase, so their consumer surplus rises by PP1SR. Those who have switched to Eurostar UK following the reduction in generalised costs, QQ1, however, were not prepared to incur the previous higher costs of P (point T), so on average only benefit from half of the increase in consumer surplus between Q and Q1, which is the area RR1S. This is the rule of the half. |

|

|

|

|

| Source: National Audit Office |