2.3 Evolution of alliancing

| Early success of alliancing The early pioneers of alliancing were experienced industry practitioners that established a new and different approach to the delivery of infrastructure projects. By focusing on project management culture and relationships, these pioneers established a new and innovative procurement strategy that provided additional value to the client. |

Historically, government procurement of infrastructure has been based on the concept of open bidding in a competitive environment. As a result, the majority of infrastructure projects have been procured using traditional competitive bidding processes. However, as the Australian construction industry has evolved and matured, the approach to project delivery has diversified. In addition to the early 'traditional' methods such as 'design and construct', and 'construct-only' contracts, projects are now being delivered using public private partnerships and alliancing.

The more traditional contractual arrangements involve a competitive tender process, are documented with technical drawings and specifications, and incorporate commercial conditions of contract and structured payment systems based on fixed pricing or schedule of rates arrangements. Traditional construction contracts also generally involve risks associated with project delivery being transferred to the constructor (to varying degrees, in accordance with a negotiated position). This approach to risk allocation has sometimes been viewed as creating an unproductive positional relationship between the 'buyer' and the 'seller', which leads to an adversarial and more litigious environment.

| What factors contribute to a 'more litigious' environment? Traditional contracting has been associated with stories of an adversarial and litigious environment. However, the introduction of 'design and construct' contracts in the 1980s was hailed by the industry as a way of reducing such an atmosphere, compared to 'construct-only' contracts. It is worthwhile to reflect on the influence of poor planning and poor communication of project objectives and scope as a cause of adversarial behaviours by contracting parties. In particular, the Guide for Leading Practice for Dispute Avoidance and Resolution (published in 2009 by the CRC for Construction Innovation) cites poor contract documentation, scope changes due to client requests, design errors or site conditions, and poor communication or management as the key factors that contribute to disputes. Arguably, these factors (rather than the form of the contract) contribute more to the root creation of any negative project relationships. |

To address this problem, the 'partnering' model was developed and promoted as a way of preventing disputes (rather than resolving disputes), improving communication, increasing quality and efficiency, achieving on-time performance, improving long-term relationships, and obtaining a fair profit and prompt payment for the designer/contractor. Partnering was not a contractual agreement, and therefore was not legally enforceable.

As the formal extension to the 'partnering' model, alliancing was first used in the oil and gas fields of the North Sea by British Petroleum (BP) in the early 1990s. When Australia embarked on its first alliance project in 1994, the Wandoo Alliance, the Owner decided to use project alliancing to:

target reduced development costs;

share time and cost risks; and

minimise use of its management team.

Australia's first alliance project was delivered using a non-price competitive process for selecting the NOPs, and relied upon the behavioural principles of good faith and trust to create the desired alliance 'culture'. In particular, the PAA required the Participants to:

achieve VfM in completing the project works;

operate fairly and reasonably without detriment to the interest of any one Participant;

use best endeavours to agree on actions that may be necessary to remove any unfairness or unreasonableness;

allow individuals employed by one Participant to be transferred to another Participant (including responsibility for their workmanship and work);

provide open book financials and other information;

wherever possible, apply innovation to all activities particularly where it could reduce cost and time for completion and improve quality;

use best endeavours to ensure that additional work remained within the general scope of works;

apportion the share of savings and cost overruns (win:win or lose:lose); and

avoid claims and litigation, arbitration and any other dispute resolution process.

From 1995 to 1998, the alliance delivery method became more sophisticated. The focus remained on ensuring a spirit of trust and cooperation, but the notion of a decision-making process based on 'what is best for the alliance is best for my organisation' also emerged. A number of new principles were also developed, including:

applying tender and selection processes based on factors other than price;

using the best people for each task/role;

creating a no blame culture;

establishing a clear understanding of individual and group responsibilities and accountabilities within the alliance governance structure; and

emphasising business outcomes.

With the significant growth of the infrastructure market over the last decade, the use of alliancing has also enjoyed significant growth, and is now considered a mainstream approach to delivering projects. Collaboration and trust remain strong themes, and most principles and practices of the original alliances remain key features of alliancing today. These include:

best-for-project focus;

unanimous decision making;

commitment of best-in-class resources;

commitment to developing a culture that promotes and drives outstanding outcomes; and

open, transparent and honest communication.

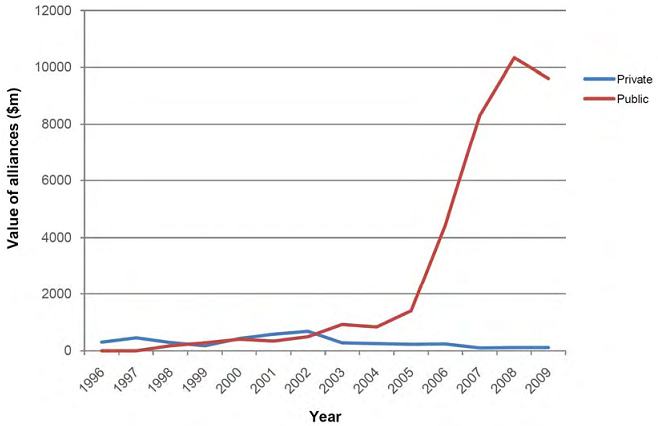

Figure 2.5 compares the public sector and private sector use of alliancing.

Figure 2.5: The value of alliancing projects undertaken by sector 20

The above graph illustrates that the use of alliancing in the private sector has been relatively static while its use in the public sector has increased significantly. Although it is unclear why there is such a significant difference, it is clear that alliancing is used extensively by the public sector in Australia. This confirms that alliancing has matured into a mainstream method of delivering infrastructure projects across the public sector. Many people in the construction industry have been exposed to a number of alliancing projects, and for some practitioners, alliancing is their predominant experience.

| When first introduced, alliancing was an innovative approach to project delivery but it is now commonly used to deliver projects across all Australian jurisdictions and is considered a mature (rather than emerging) delivery method. That is, alliancing has become a business-as-usual approach to delivering Government infrastructure projects. The next evolution of alliancing will involve Owners taking a more tailored approach. In particular, the leading practice set out in this Guide signals a shift away from use of the 'traditional/conventional' alliance model. This shift reflects insights from government and industry gained from their experience in delivering alliance projects, and implements the procurement requirements that satisfy government's commercial and policy objectives. This shift away from the 'traditional' approach to alliance contracting should enhance the VfM outcomes achieved by Owners. |

The possibility of achieving better VfM when delivering public infrastructure was revealed through recent research into current Australian alliancing practices.21 The research demonstrated a need for existing guidance to be updated to reflect leading practice in the use of alliancing in the public sector. This Guide seeks to further develop and enhance the use of alliance contracting by addressing the issues raised in the research, and by building on the experience gained in recent years.

The language of alliancing has also evolved as the delivery method has matured. Guidance Note No 122 has been developed to assist in achieving consistency in the meaning, understanding and application of specific terminology commonly used in alliance contracting.

_________________________________________________________________________________

20 In Pursuit of Additional Value - A benchmarking study into alliancing in the Australian Public Sector, DTF Victoria, October 2009

21 In Pursuit of Additional Value - A benchmarking study into alliancing in the Australian Public Sector, DTF Victoria, October 2009.

22 Refer to the Guidance Note No 1, Language in Alliance Contracting: A short Analysis of Common Terminology, Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development, Commonwealth of Australia, March 2011.