4.3 Funding

Whilst annual spending on Australia's infrastructure has been higher in the last five years than in the preceding 20 years, the rate of expenditure appears insufficient to maintain current levels of service into the future. Analysis of future fiscal pressures suggests that governments will struggle to maintain current levels of infrastructure expenditure in the medium to longer term. This is particularly relevant for the transport sector and, to a lesser extent, the water sector.

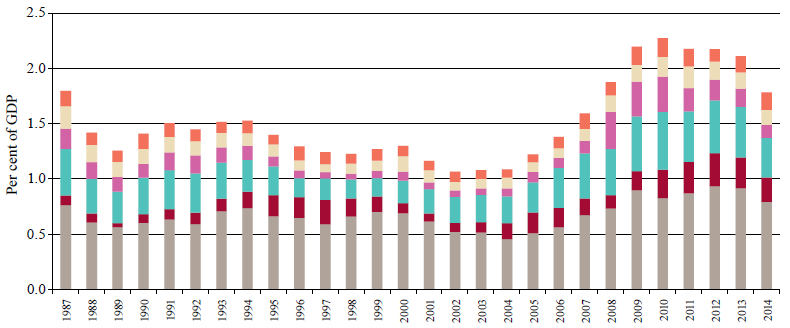

As shown in Figure 12, infrastructure outlays by Australian governments have increased substantially since the middle of the last decade, particularly for transport.

Private investment in infrastructure has also grown, partly as the private sector has become a larger owner and developer of infrastructure, and partly as infrastructure has been developed to support new resources and energy developments.

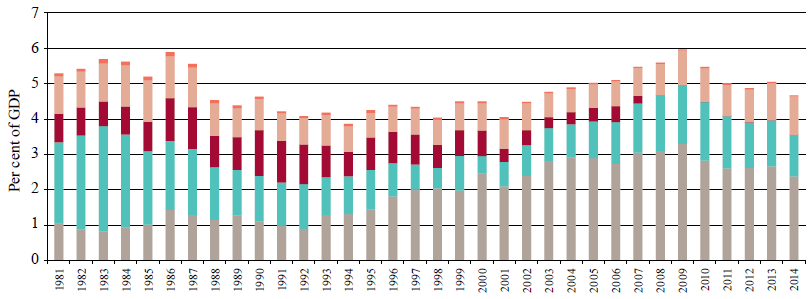

As shown in Figure 13, overall investment in economic infrastructure has generally varied between four and five per cent of GDP for the last 30 years.

Audit finding 26. Over recent years, rates of public and private investment in infrastructure have been higher than the long-term average. |

Figure 12: Engineering construction work for the public sector - 1987 to 2014 (year ending 30 June)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Infrastructure Australia analysis of Australian Bureau of Statistics (2015) data

Figure 13: Public and private investment in transport, electricity, gas, water, waste and telecommunications infrastructure - 1981 to 2014 (year ending 30 June)

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Source: Infrastructure Australia analysis of Australian Bureau of Statistics (2015) data

As noted in separate analysis commissioned for the Audit,101 there is evidence of underspending on infrastructure maintenance. In addition, in some cases, infrastructure providers' maintenance of existing infrastructure is underpinned by government subsidies. For example, various governments subsidise the cost of electricity supply in regional locations.102 The fiscal challenges facing governments suggest that this could become increasingly difficult to sustain. Equally, though, moving to more cost-reflective pricing for services in smaller regional communities is likely to raise difficult issues for those communities.

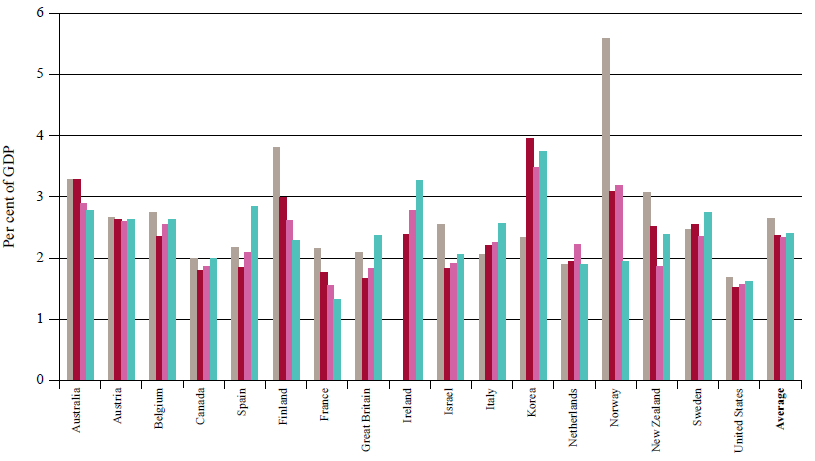

As shown in Figure 14, there is also some evidence Australia has been spending more than many other countries. However, as noted above, this approach does not address country-specific cost pressures or advantages that might justify a departure from an international average level of expenditure. Nor does it address differences in service levels.

Figure 14: Transport, storage and telecommunications outlays - OECD countries - 1970 to 2006

1970-79

1970-79  1980-89

1980-89  1990-99

1990-99  2000-06

2000-06

Source: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (2009)

Audit finding 27. The current level of public sector expenditure - especially in the transport sector, which remains largely funded by government rather than user charges - may be unsustainable in the face of increasing budget pressures to fund welfare and health services. |

Various projections of government finances highlight the significant challenges facing all governments in meeting community expectations, including expectations of our infrastructure. For example, analysis undertaken by the NSW Government concludes that, even assuming a fall in transport outlays as a percentage of Gross State Product (GSP) compared to recent expenditure:

… a fiscal gap of 2.8 per cent of GSP is projected to open up by 2050-51. To put that in context, the gap will be $11.5 billion (or around 20 per cent of budget expenses) based on 2009 10 GSP. If measures are not taken to close this gap, net debt will rise from 2.3 per cent of GSP in 2009-10 to an unsustainable 119 per cent by 2050-51.103

Infrastructure Australia stated in its 2012 report to the COAG that:

The projections of fiscal gaps suggest that, if the current approach to funding is maintained, the projects that are developed in our cities over the next 20 years may be amongst the last that can be funded through conventional government means.104

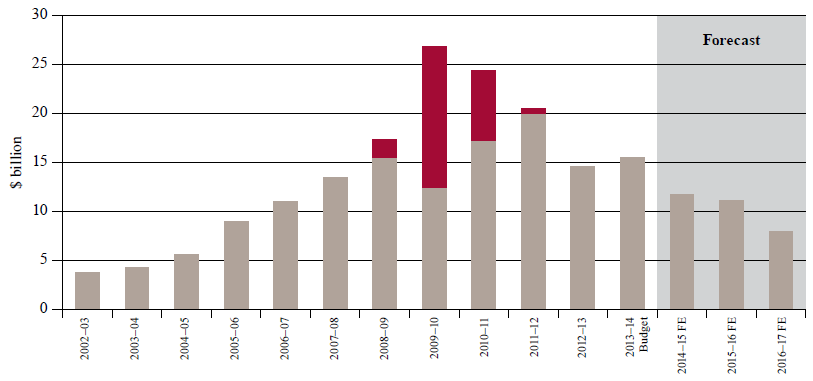

A more recent study published by the Grattan Institute bears out this analysis. Figure 15 shows that, in their 2013 budgets, state and territory governments planned to reduce capital expenditure materially. The figures are for the 'general government sector', i.e. they exclude expenditure by government trading enterprises but include most transport expenditure.

Figure 15: State and territory capital expenditure - general government net acquisition of non-financial assets ($ billion, 2013 prices) - 2003 to 2017

Commonwealth stimulus package

Commonwealth stimulus package  Capital expenditure

Capital expenditure

Notes: 2012-13 are estimated actuals. 2013-14 and forward estimates (FE) are budgeted figures.

Source: ABS (2012) cat 5512, Treasury (2008), Part 2, Table 2.1, State and territory budget papers 2013-14.

Source: Daley and McGannon (2014), p. 38

Measures introduced by the Australian Government in its 2014-15 budget to encourage infrastructure spending, such as the asset recycling initiative, have helped to maintain capital expenditure at a higher level than other governments were budgeting in 2013. Nevertheless, the jurisdictional budgets from 2013 provide a clear indication as to their intentions about the likely direction of infrastructure outlays.

Current arrangements for the funding of land transport are deeply flawed and represent the most significant opportunity for public policy reform in Australia's infrastructure sectors.

Users already contribute to the cost of transport infrastructure:

■ motorists contribute to the cost of the road network through state charges such as registration and licence costs, and through the Australian Government's fuel excise;

■ train, bus and ferry users make a contribution to the cost of operating public transport systems through the purchase of tickets; and

■ in the freight rail sector, access charges are aimed at meeting most, if not all, of the cost of maintaining the rail infrastructure.

However, with some limited exceptions (e.g. tollways and some mining related railways), the development and maintenance of Australia's land transport networks is funded primarily through government outlays.

There is relatively little transparency in these arrangements. It is unclear how flows of funds from the revenue sources are then linked to transport outlays and the performance of the networks.

A number of factors strongly point to the conclusion that the existing arrangements for funding the development of Australia's transport networks are unsustainable and need to be changed.

First, in the road transport sector, the amount raised from fuel excise is likely to decline over time. More fuel-efficient vehicles and the wider use of hybrid and electric vehicles will reduce the use of fuel and therefore the amount raised from fuel excise. Moreover, as noted elsewhere in this report, per capita vehicle usage (measured in vehicle kilometres travelled) is flattening out. The net effect is that less excise revenue is collected and less is therefore available to fund transparent needs.

Australia is not alone in facing this challenge, other countries are dealing with the same trends. In the United States, in particular, there have been regular debates about the durability of its existing transport funding arrangements in the face of these trends.

Secondly, current arrangements do not encourage the most efficient use of the existing transport networks. As shown in the sections of this report dealing with urban transport, peak hour demand on many urban transport networks significantly exceeds the capacity of those networks. The result is congestion on the nation's roads and overcrowding on parts of the public transport network. Yet, at other times of the day, these same networks have spare capacity.

Thirdly, without funding reform, there will be insufficient funds available to provide the infrastructure required to sustain Australians quality of life. The cost of new projects (both those already planned and those yet to be defined) and the cost of maintaining existing assets will almost certainly exceed the funds that governments will plausibly have available to spend on transport. Evidence of this can already be seen in the periodic debates between governments about their respective funding shares for new projects.

Governments therefore need to investigate alternative funding mechanisms to meet infrastructure needs. The Productivity Commission recently acknowledged the need to consider greater use of direct charges on users and other beneficiaries. It saw this shift to greater use of direct charges being justified on efficiency and equity grounds.105 The Commission reviewed and found merit in governments considering:

■ user charges, including road user charges and public transport charges; and

■ value capture, including betterment levies, tax increment financing and property development.

In response to the Commission's recommendations in this area,106 the Australian Government has responded broadly as follows:

■ Recommendation 4.1 - In relation to pilot studies on how vehicle telematics could be used for distance and location charging of cars and other light vehicles, and a future shift to direct road user charging for cars and light vehicles - the Australian Government supported the recommendation in principle as a long-term reform option. However, the Government noted a range of complex issues (equity, technology, privacy and the availability of alternatives) that would need to be worked through, including with other governments, industry and the community;

■ Recommendations 8.1 and 8.2 - In relation to the establishment of Road Funds by state and territory governments and local government groupings (and covering road funding, investment and maintenance, amongst other things) - the Australian Government indicated: (a) it has begun working with state, territory and local governments to investigate options for a road fund, including focusing on commercial freight routes; and (b) that it is considering the broader, long-term issues around wider application of road pricing.107

The Government's recent tax discussion paper has also noted arguments in favour of user charging, and pointed to the Australian Government's response to the Productivity Commission's recommendations (see above).

Funding the infrastructure needed to support productivity growth in Australia is likely to require greater revenues than are presently available to governments. Successive editions of the Intergenerational Report (and equivalent analysis prepared by some state governments)108 have shown that Australian governments continue to face significant fiscal pressures. Any decrease in existing indirect charges and taxes on road users would mean that fewer funds would be available for infrastructure investments, and more funds would need to be found from other revenue sources. Avoiding the anticipated budget deficits109 is likely to require significant limits on future government outlays. It would be surprising if spending by governments on infrastructure alone was exempt from these limits.

None of these issues are new. The Henry review of taxation110 comprehensively outlined the need for reform in this area. Economic regulators in the states have addressed these issues on a number of occasions. COAG considered transport funding and pricing as part of its work on urban congestion as far back as 2006. Industry bodies have highlighted the need for change.111 More recently, the Competition Policy Review Panel discussed the introduction of cost-reflective pricing and linking the revenue raised to road provision. It recommended reducing indirect charges and taxes on road users to offset increases to road user charges, in order to prevent higher overall charges for consumers.112

Yet, beyond a few references in some transport plans to transport pricing as a long-term possibility, and faltering and slow progress on heavy vehicle charging, no substantive action has been taken by governments. Some jurisdictions oppose even the application of project-specific road tolling as a matter of state policy.

The private sector will only invest in a project if it is able to earn a return on its investment. That return can only come from user charges or from governments in the form of availability charges (however, availability charges themselves represent a call on future government funds).

This unsatisfactory state of affairs needs to end. The debates on these matters will be difficult and sometimes fraught. Governments and oppositions, along with industry and other stakeholders, will need to display leadership and integrity in initiating and participating in these debates.

Australia needs to consider a broader system of transport pricing, both for road and public transport. This is not to say that governments will not need to continue to invest in the country's transport networks. There will be situations where broader public policy objectives, including those associated with social and sustainability outcomes, can only be achieved with some level of government investment. However, these payments should be provided transparently, following exhaustive planning and demonstration of the contribution towards achieving those public policy outcomes.

Although the issues are most pressing in the transport sector, to varying degrees, similar issues arise across the water, energy and telecommunications sectors.

Audit findings 28. Current arrangements for the funding of land transport represent the most significant opportunity for public policy reform in Australia's infrastructure sectors. 29. Government funding alone is unlikely to be sufficient to provide the infrastructure that Australia requires. Maintaining or strengthening conditions to facilitate private sector investment in and operation of Australia's infrastructure networks is fundamentally important. 30. The country needs to consider a broader system of transport pricing, both for road and public transport. |

Local councils own and manage a large part of Australia's infrastructure networks, notably in the transport and water sectors.

Around 670,000 kilometres of roads are under the control of local councils (approximately 74 per cent of the total road length across the country). The roads were valued at approximately $165 billion in 2011. The condition of the assets and quality of service is variable. A 2014 survey conducted on behalf of the Australian Local Government Association found that around 10 per cent of local roads and bridges controlled by the respondent councils were in a poor or very poor condition.113

Local water services, especially in smaller rural communities, do not consistently deliver water that meets relevant water quality standards. As noted elsewhere in this report, maintenance of local water services is often underfunded.

Some councils are likely to find their local rate base come under pressure, e.g. if the local economy shrinks and/or younger residents move out of the area, leaving a smaller (probably older) population with limited or fixed incomes.

In rural areas especially, these dual challenges of high costs/service backlogs on the one hand and limited revenue on the other, are likely to persist. However, it will not be easy for the Australian Government and/or state/territory governments to respond with materially greater financial support for local communities as their budgets are under pressure too.

In these circumstances, reform of local government will be necessary. As systems of local government are a state/territory responsibility, reform will need to be driven largely by those governments and local government itself. Economies of scale will have to be secured, either through council amalgamations and/ or the development of shared systems for asset management and resource sharing. In this regard, local government is increasingly exploring resource sharing initiatives.

Audit finding 31. Amalgamation of local government in some areas, and other reforms such as shared services arrangements, will be necessary if local councils are to have the scale and financial capacity to meet their local infrastructure responsibilities. |

_________________________________________________________________________________

101. GHD (2014)

102. AECOM (2014)

103. New South Wales Government (2011a), p. i

104. Infrastructure Australia (2012c), p. 46

105. Productivity Commission (2014a), p. 142

106. Productivity Commission (2014a). See, in particular, recommendation 4.1, 8.1 and 8.2 at pp. 42-43.

107. Australian Government (2014d), pp. 11-12

108. See, in particular, the analysis in New South Wales Government (2011a).

109. Australian Government (2015a), pp. 46-48

110. Australian Government (2010b)

111. Infrastructure Partnerships Australia (2014)

112. Competition Policy Review Panel (2015), p. 217

113. Jeff Roorda and Associates for the Australian Local Government Association (2014), p. 5. Approximately 70 per cent of councils across Australia responded to the survey.

General govt (State and local)

General govt (State and local)