7.4.3.5 Investment

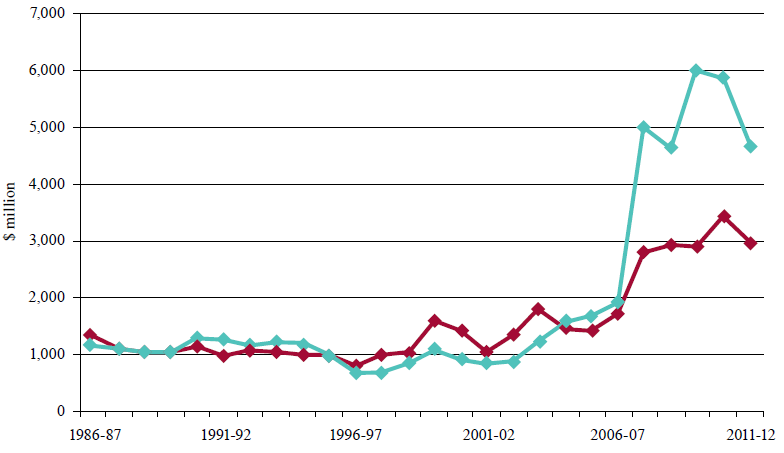

Figure 46 illustrates a dramatic increase in water and sewerage infrastructure spending across Australia since 2006-07. A large part of this is attributable to investments by several state governments in constructing desalination plants and recycled water schemes to drought proof their cities and towns in the face of the millennium drought. This increase also represents upgrades to ageing water infrastructure across Australia, as well as significant investment in on- and off-farm irrigation infrastructure to improve the efficiency of irrigation, particularly in the Murray-Darling Basin, but also in Tasmania and in other parts of Queensland outside the Basin.

Overall, urban water demand in Australia will continue to increase with population growth. However, this increase will be moderated by the following factors:

■ Utilities and planning regulations can influence demand through management measures and education campaigns that target household water efficiency, and mandatory standards for water efficient appliances.

■ Demographic changes, such as the ageing population and urban planning. Strategies to increase density of urban development will lead to reduced housing block and garden sizes, which in turn will reduce individual household demand.

In the irrigation sector, demand will continue to be influenced by water availability and macroeconomic factors such as commodity prices, market access and exchange rates. Other factors that will have an impact on future demand include more efficient irrigation technology and practices, and the extent to which greenfield irrigation areas are established.

In the Murray Darling Basin, water availability for consumption is capped under the Murray Darling Basin Plan. Consequently, future demand will need to be met through irrigation efficiency savings and operation of the water market.

Outside the Basin - most notably in northern Australia, where water resources are not fully committed - future growth in demand will depend on the viability of new irrigation enterprises, taking into account the costs of new dams and groundwater development schemes.

Figure 46: Value of water infrastructure engineering work - 1986-87 to 2011-12 (2011 prices)

Water storage and supply

Water storage and supply  Wastewater and sewerage

Wastewater and sewerage

Source: Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics (2013a)

In addition to centralised supply models, education campaigns and incentives programs have been used to encourage decentralised supply options such as rainwater tanks, grey water systems and stormwater harvesting at the municipal or local scale. In Perth and Melbourne, schemes were introduced to fund irrigation efficiency programs, with rural water savings used to augment urban supplies. In Melbourne, these schemes were decommissioned following a change of government.

Expanding the coverage of technological solutions, such as automation, remote telemetry and electronic sensing, can provide significant savings in operational costs and improved asset condition monitoring. These solutions can extend the life of existing assets and improve service delivery, leading to reduced costs of supply and water savings across the network.

Despite recent investments in water infrastructure, the Audit has identified significant areas of concern for the sector. Underinvestment in maintenance of some water assets, and ageing infrastructure, will require an increased focus on maintenance and renewal, while the borrowings of urban water utilities should be monitored to ensure that commercial operations and future investment capacities are not compromised.

Audit findings 80. A number of urban water utilities have increased their borrowings over recent years, for various reasons, with consequential impacts on their commercial performance and their ability to take on additional debt. 81. Underinvestment in maintenance of some water assets, and ageing infrastructure, will require an increased focus on maintenance and renewal. |