Introduction

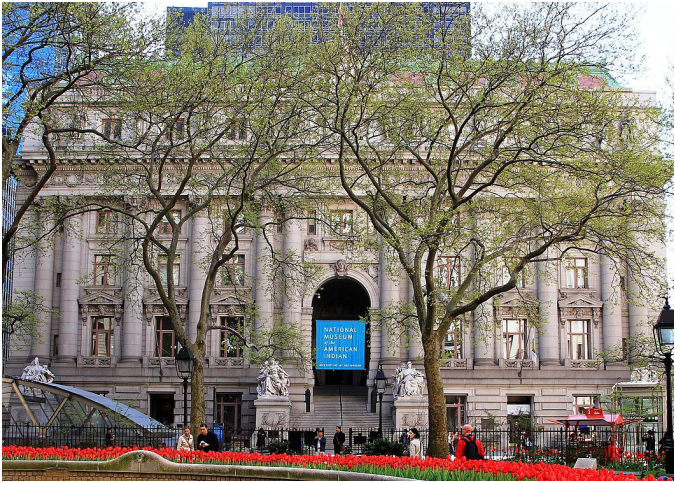

The National Museum of the American Indian-New York at the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House in New York City.

Ingfbruno/Wikimedia Commons

The unmet needs for infrastructure investment have been documented as reaching into the trillions of dollars, yet the limitations on the financial capacity of government have never been more acute. One possible solution that has surfaced is the public/private partnership-a means of financing public infrastructure that relies on various forms and degrees of private investment.

Other industrialized nations, such as the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, as well as state and local governments in the United States, have turned to public/private partnerships (PPPs, or P3s) to help address these needs. Some argue that PPPs expand the government's capacity for long-term financing of much-needed transportation, water, and real property infrastructure by providing direct access to private capital.

However, for a variety of reasons, the ability of the U.S. government to use PPPs for federal infrastructure projects remains limited. That limitation is due, in large part, to the federal government's inability to enter into project-specific, long-term financial obligations that are essential to access private capital. Although PPPs have become a subject of policy discussion and debate, they are not widely used as a means of federal support for financing our nation's federally funded infrastructure.

There are, however, a number of instances where the federal government has embraced PPP approaches. For example, the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act has been instrumental in facilitating the use of PPPs for highway projects. The 2014 Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act will potentially allow the availability of similar project delivery models in the water and wastewater sectors. Nevertheless, the ability of the U.S. government to use PPPs to finance projects in other asset classes-particularly those intended for use by or for the direct benefit of agencies, such as federal real property-remains limited, due in large part to current budgetary rules for project scoring.

| The U.S. Infrastructure Deficit According to a 2015 report by the Office of Economic Policy in the U.S. Treasury Department,a underinvestment in public infrastructure imposes massive costs on our economy. Motorists in the United States spend 5.5 billion hours annually in traffic, resulting in costs of $120 billion in fuel and lost time. U.S. businesses pay $27 billion in additional freight costs because of the poor condition of roads and other transportation infrastructure. Continuing deterioration of water systems throughout the United States results in about 240,000 water main breaks annually, causing significant property damage and costly repairs. Yet outlays for transportation and water infrastructure made by all levels of government, as a share of gross domestic product, have declined in recent decades. A 2014 report by the Government Accountability Officeb indicates that the Federal Real Property Profile estimates for deferred maintenance and repair in fiscal year 2012 were $4.7 billion for the General Services Administration, $5.1 billion for the Department of Energy, $14.4 billion for the Department of the Interior, and $12.5 billion for the Department of Veterans Affairs. a. Elaine Buckberg, Owen Kearney, and Neal Stollerman, "Expanding the Market for Infrastructure Public-Private Partnerships: Alternative Risk and Profit Sharing Approaches to Align Sponsor and Investor Interests," Office of Economic Policy, U.S. Department of the Treasury, Washington, DC, April 2015. b. "Federal Real Property: Improved Transparency Could Help Efforts to Manage Agencies' Maintenance and Repair Backlogs," GAO-14-188, U.S. Government Accountability Office, Washington, DC, January 23, 2014. |

In general, federal budget scoring concepts are based on the premise that fiscal actions should be fully accounted for at the time an action is taken. This principle provides accountability, transparency for taxpayers, and flexibility for future decision makers as they are not locked into long-term agreements of their predecessors. These precepts combine to meet the goal to control and measure federal spending. However, as currently implemented, the practice of scoring capital expenditures (or capital leases) fully in the first year of obligation has the potentially unintended effect of favoring operating costs, entitlements, or tax expenditures over capital or other asset-based funding priorities. More starkly put, because of differences in budgetary accounting treatment, federal spending is tilted toward transfers over investments. Furthermore, the economic principle of "user pays"-that is, the beneficiary of a public expenditure should help defray costs-is not brought to bear under this approach.

The current guidelines used to score privately financed infrastructure came about in the early 1990s in reaction to perceived abuses in the area of real estate lease purchases. At the time those rules went into effect, the federal government elected to use the principles embodied in Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) Statement 13, which is a set of accounting rules designed to govern how private sector companies either expense or capitalize leases. Now that more than 25 years have passed, it is necessary to revisit the continued application of these principles. This reassessment is particularly important because the accounting rules that served as the basis for the current scoring methodology have themselves evolved and have been amended, now distinguishing capital leases from other forms of PPP and privately financed infrastructure, such as concessions (as contemplated under Government Accounting Standards Board Statement 60).

Moreover, these current budget scoring policies do not reflect global norms. As set forth in OMB Circular A-11, Appendix B, our federal government has opted-by policy-to use the "control methodology" for determining the budgetary treatment for PPP projects. This approach focuses principally on the level of government control of services to determine whether the asset should be classified as "on balance sheet" and scored as a capital purchase (essentially, as debt), with all obligations associated with the PPP (including future payments) being scored upfront.

The risk/reward methodology, however, is a more widely applied approach, as codified, for example, in European System of Accounts ESA10 and ESA95. The fundamental principle in the risk/reward methodology is that economic ownership of an asset lies with the party that possesses the asset and carries the risks, benefits, and burden in connection with the asset. Where most of the project risk has been transferred to the non-government partner, then the assets should be classified as "off-balance sheet," and any budget payments would be scored like an operating lease, over the life of the project. If project risk is not transferred, the asset would be classified as "on balance sheet" and scored upfront. This approach, which is well regulated and understood on a global level, achieves the same objectives as current OMB budget scoring guidelines, while more accurately reflecting the underlying risk allocation contemplated in PPP arrangements.

Although some members of the project Advisory Group came to the discussion thinking that budgetary scoring rules are a major problem and need immediate reform, the group's position evolved, and they ultimately concluded that the current scoring regime could work well, if it were applied rigorously and universally. In fact, the members of the Advisory Group recognized that it may be many of the exceptions to current scoring procedures that are the real problem. Rather than recommend that the number and types of exceptions be expanded, their final unanimous recommendation is that the federal government eliminate the exceptions and create a level playing field for evaluating the relative costs and merits of different projects and financing structures.