6.1.8 Financial principles of PPP contract design

The theoretical literature on PPPs has given little attention to the financial dimension of contracting. It is clear that PPPs have been attractive for governments trying to make their accounts look good, thereby using public accounting rules that do not correctly capture government assets and liabilities. PPPs then create the impression that public debt has not grown as much following an investment project. We will abstract here from such public accounting motives since they do not alter the efficiency of PPP.

Beyond pure risk sharing, it is important to think about the effects of the funding mechanism on incentives. While the literature stresses incentives linked to allocating ownership rights under traditional service provision and PPP, it does not explicitly take into account that the contractor has to honor and remunerate external finance such as outside equity and debt. Traditional corporate finance has stressed, however, that large outside equity or debt can lower incentives to exert effort (see, for example, Jensen and Meckling 1976 and Myers 1977) since effort partly benefits external investors (outside shareholders or creditors). One should therefore be aware of potential drawbacks of relying on highly leveraged private contractors to undertake public projects.

Things may be different, however, if 'bundling' also concerns the financing of the project. For instance, assume that bundling requires the consortium to buy and finance the asset. Typically, the consortium will have to seek external finance, unless it has enough funds: this implies that part of the return of the project will accrue to outside investors, and not just to the consortium. With outside equity, the consortium offers outside shareholders a constant share of what it gets by extracting consumers' willingness to pay. Having to share the returns on its efforts with outside shareholders, the consortium has less incentive to exert effort.

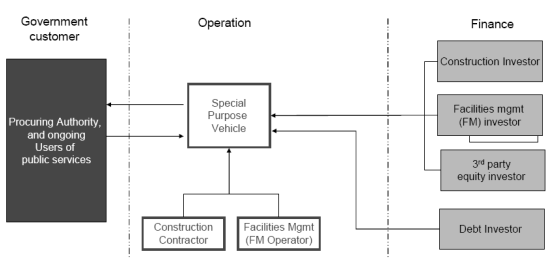

The Consortium Model with Financing and Operating Phases

Source: Adapted from Levine and Robinson, 2006. ELA-FFW, London, UK.

This is a case where PPP backfires: on the one hand, the bundling of building and construction gives appropriate effort incentives to the consortium; on the other hand, since the consortium has to rely on outside equity to finance the asset, the positive incentive of bundling is undone because outside shareholders end up getting too much of the return on the consortium's effort. In fact, outside equity is not the optimal external financing mode in this case: one can do better with debt, which maximizes effort incentives for a given expected repayment to the outside financiers by maximizing the difference between the consortium's payoff in 'good' states of the world and 'bad' ones.

Although debt is better than equity at preserving the consortium's incentive to exert effort, it is true nonetheless that there will be cases where it cannot be done while satisfying investors' participation constraint. The general lesson from this sub-section is that, by insisting on external finance, a PPP can undo the desirable incentive effect that bundling the construction and operation phases may achieve. In discussing the downsides of external financing for PPPs we have so far attributed a minimalist role to outside equity and debt: we have stressed the income rights attached to these instruments, but we have abstracted from their associated control rights.

Why outside finance may stifle the efforts of PPP contractors? We consider a stylized infrastructure project. The willingness of consumers to pay for the infrastructure service is a random variable being either a low V 0 or a high V1. The realization of consumer willingness to pay depends on effort exerted at the building stage. Specifically, the realized willingness to pay will be V0 with probability 1 - k - e and V1 with probability k + e, where k is a positive constant and e is the effort exerted at the building stage. Effort, e, can only take two values: 0 and e* > 0, with e* indicating the profit maximizing level of effort. With outside equity, the consortium keeps a share 1- β of profits and chooses e to maximize: (1 - β)(1 - k - e) V0 + (1 - β)(k + e)V1 - e. This will lead to a choice of effort e* only if: (1) (1 - β) (V1 - V0) ≥ 1 or (2) β ≤ 1 - 1/(V1 - V0). The left-hand side and the right-hand side, respectively, of (1) show marginal benefit and marginal cost to the consortium of exerting effort. Condition (1) - which can be rewritten as condition (2)- thus says that the share of profits retained by the consortium (1-β) must be big enough to induce the consortium to exert effort. At the same time, the share of profits accruing to outside shareholders has to be large enough to induce them to supply the initial financing I. Specifically, shareholders' participation constraint is: (3) β (1 - k - e*) V0 + (k + e*)V1 ≥ I or (4) β ≥ I / (V0 + (k + e*)(V1 - V0)) Source: Adapted from Dewatripont and Legros (2005). |

There are many debates about the various ways in which shareholders can transform their 'formal authority'-managers are by law most of the times instructed to pursue shareholder interests-into real 'real authority' through various mechanisms of corporate governance. Corporate finance, on the contrary, analyzes various safeguards against the divergence between managerial conduct and shareholder interests. For example, the role of boards of directors, transparency of information, and the regulation of takeovers are the main areas of concern.