6.2.1 Price variations

Since long term contracts are by definition and inevitably incomplete, auctioning procedures are not always effective in identifying the most efficient private operator to invest and operate a public service. Nor, auctioning allows to settle an ex ante price that reflects economic optimization of the provider and that is accessible to the purchasing power of the demand. Moreover, ex post exogenous conditions as well as ex ante opportunism may disturb the result of actions and the settlement of prices. Deciding ex ante what has to be done ex post is a way to stabilize the contract by avoiding (as much as possible) renegotiation. However, stability of prices is obtained at the cost of making the contract maladapted to unanticipated circumstances (Athias-Saussier, 2005).

For instance, Guasch (2004) proposes a model for appropriate structure of tariff and price setting under price-cap regimes. This structure applies to the first year of the contract and then revisions are undertaken. He proposes to internalize in process or guidelines the adjustment of tariffs and prices in a five-year period interval. Although this model is effective to minimize the probability of renegotiations, it does little to assure stability given price variations during the complete life-cycle of the PPP. This last point is important to address because prices may even be over evaluated in the initial phases of the project because competitors will want to anticipate transaction costs associated with renegotiations and conflicts (Bajari-Houghton-Tadelis, 2004).

Renegotiation might be constrained by the level of ex post competition. Thus, implicit relationship dimensions (ex post competition) could play a role in the efficiency of contracts. The important aspect of ex ante considerations in contracts to cope with price variations has to do with the fact that initial award criterion may involve not just one price, but a vector of prices to be determined depending on the types of costumers and the level of quality provided. Furthermore, if operators are selected on the basis of their price bids (which reflect their further tariff structure), then there is a risk of the "winner's curse", since best offer may come from most optimistic operator.

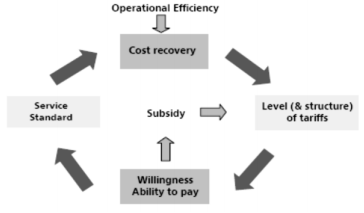

Contracts of endogenous duration may offer a partial solution to the problem (Engel, Fischer and Galetovic, 1997). Consequently, tariffs need to balance a number of objectives: (i) stipulated service standard and associated costs, (ii) customers' willingness and ability to pay, (iii) resulting cost recovery, (iv) required economics (return on investment) for private operator, and (v) need for/availability of subsidies. The right combination of factors must be determined through an iterative optimization process using the PPP project model.

The iterative process of tariffs, value, operations and service standards

This process is made more complex if differentiated/complex tariff structures (e.g., unit price as a function of consumption to help low-income users) or tariff adjustment mechanisms (e.g., for input cost changes, high inflation, exchange rate changes) are used. It is critical to employ qualified and experienced specialists for this modeling and optimization task.

The following objectives provide an appropriate starting point for designing tariffs in a volatile environment:

• Cost recovery/return on investment,

• Incentives for efficiency,

• Fairness and equity, and

• Simplicity and comprehensibility.

Finally, the combination of service standards (costs) and tariffs (revenues) in the contract determines the commercial viability of a project. Beyond that, the private operator has the chance to improve the ultimate financial outcome by being particularly efficient in investment and operations. Therefore, a private operator will only get involved in a project if it sees a fair chance to make a profit given a predetermined set of service standards and tariffs.

To expect one set of tariffs, or even a tariff structure or regime, to remain viable and appropriate over the typical life of a PPP project is unrealistic. It is therefore essential to define practical rules for adjustments. This requires defining in the contract:

• The triggers or drivers for a price adjustment, such as changes in raw material prices (such as oil prices for power), inflation, and exchange rate fluctuations (where the operator had to assume non-hedged foreign currency exposure);

• The mechanisms by which the adjustment will be made, including cost plus and price-cap regulation [as proposed by Guasch (2004) and others];

• The frequency of adjustments including cost pass-throughs, tariff indexation, tariff resets, and extraordinary tariff adjustments.

Regulatory Structures of Pricing When designing a PPP or concession contract there are choices regarding the regulatory regimes. Guasch (2004) revises two salient choices, the rate of return and the price cap regulation. In general, PPPs are subject to higher returns of investment under price-cap regulation. Latin American countries have experienced problems because contracts have not considered or accounted for the full implications of the regulatory regimes on efficiency and profitability. In practice, both regimes tend to converge in the long-run, and the level of convergence depends highly on the frequency of tariffs and pricing reviews. In Chile there has been an outstanding result in the Energy sector. Chile's method of Electricity pricing is distinctive because of the innovative approach to rate of return regulation. The price system includes regulated rates for consumers with peak demand of less than 2 megawatts and freely negotiated rates for the rest. The final price to regulated consumers has two components: a node price at which distribution companies buy power from generators and from transmission grid, and the value-added from distribution. The value-added of distribution is calculated every 4 years. The procedure involves determining the costs of an optimally operated firm and setting rates that provide a 10% real return over the replacement value of assets. These rates are then applied to the real companies to ensure that the average return falls between rates of return on assets of 6% and 14%. If the average actual return falls outside this range, the rates are adjusted to reach the upper or lower limit, depending on whether they fall above or below. The operating costs of the benchmark "efficient firm" and the replacement value of assets are based on a weighted average of estimates made by the industry and the regulatory agency. Source: Kerf, Michel. 1998. Infrastructure Concessions: A Guide to Their Design and Award-Privatization Tool Kits. Washington, DC: World Bank., and Guasch, JL. 2005. Granting and Renegotiating Infrastructure Concessions: Doing it Right. WBI. |

In PPP contracts variations of price (VOP) clauses need to be negotiated between the parties to cover from changes in prices, costs, inflation, etc. Contingencies bid prices for the initial period of the contract is recommended to be included with an additional set of clauses that identify key managerial actions to be taken when prices fluctuate based on predetermined benchmarks. For example, procurement strategies must clearly explain how inflation risks are to be managed in the contract and pricing teams conformed. Pricing arrangements for longer term contracts should be exposed to investment appraisal to identify the approach that offers the best value for money.

In addition, price reviews, are said, need to be stipulated explicitly in the contract in order to (i) adequate tariffs or unitary payments to long-run changes in the private partner's uncontrolled costs, e.g. technological progress modifying the cost structure, introduction of new inputs whose prices are not tracked closely by the available indexes, etc.; (ii) provide a value testing provision where adjust prices periodically according to the evolution of the costs of service provision. In 'value testing' procedures, information on costs is collected directly, so implementing the procedures involves higher transaction costs compared to a simple, mechanic inflation indexation. But there is an important advantage: an adjustment of service charges based on accurate, specific information on costs closely tracks the private partner's uncontrolled costs, and thus provides incentives to control costs and properly select suppliers; and (iii) provide market testing and benchmarking aiming at ascertaining the market value of the main inputs involved in providing the service through a re-tendering among potential suppliers of these inputs. The information collected is used in the price review for tariffs or unitary payments and have information on market prices of inputs is gathered to compare the private partner's costs and adjust prices.

In implementing these procedures, a choice should be made on when price reviews and testing will take place. In fact, a trade off exists regarding the length of the regulatory lag. If the first review is planned to occur in an early phase of the project, a potential operator could bid aggressively, offering a low tariff and expecting the review to increase it soon after the contract is awarded. On the other hand, if there is a lengthy period before the first review, the private-sector party is largely exposed to the risk of misalignments between the initial fixed price and the operation costs, and thus it may require a higher service charge level. In practice, price adjustment clauses are an important element in the tariff regulation for services where the private partner's revenues result from charging final users. If the price review is frequent and the price adjustment is backward-looking, i.e. the regulatory lag is small and past changes in costs are considered to compute a new tariff level, the private-sector party has little incentive to undertake cost-reducing efforts.