A Taxonomy of Distress Situations

To facilitate the analysis of the various sources and consequences of distress situations in PPP contracts, a distinction may be drawn between three different types of distress, depending on the specific aspect of the contract that is affected: economic, financial and operational. A second distinction needs to be drawn based on the origin of the distress situation, be it endogenous to the company or contract (internal) or caused by exogenous situations (external).

The first distinction allows a separate identification of the company's aspects that are affected by the distress situation in order to thoroughly analyze the possible causes and implications for the service.

A contract can be viewed as being under economic distress when the balance between contractual rights and obligations is materially altered. The key element in a situation of economic distress is a long term imbalance between revenues and economic costs148. Given the proposed separation of financial distress and economic distress, the economic analysis completely leaves out the financing structure of the firm.

A situation in which the company is unable to repay its debt (principal and/or interest) is what it is known as financial distress. Financial distress can also present itself in terms of lack of access to capital markets to raise fresh funding even if the company is properly servicing its existing obligations as they fall due.

Operational distress has to do with conditions under which the service is substantially and/or continuously affected, causing the company not to satisfy the contractual conditions of service.

The distinction between internal and external causes is critical for a division of costs and the definition of potential new rules. Every PPP contract necessarily involves the transfer of certain risks to the private sector. Such transfer of risks is key to the generation of incentives for the company to minimize costs and provide an efficient service. The preservation of such incentives requires that the company and, ultimately, its stockholders and/or creditors, cover at least a portion of the costs in any situation of distress caused by actions, behaviors or omissions of the company itself.

Table 26 presents a summary of the possible combinations of distress types and possible origins. It includes the main sources for the different types of distress associated with internal and external causes.

Table 26: Possible Combinations of Distress and Origin

| Origin Distress | Endogenous | Exogenous | |

| Agreed-upon | Not Agreed-Upon | ||

| Economic | Commercial or operational inefficiency affecting income and/or costs, causing economic imbalance in the contract | Changes in relative prices affect the costs of service provision and there is no pass-through provisons | Environmental rules force the adoption of more expensive technologies. |

| Financial | Financial decisions - debt structure and denomination - of the company | Increases in the interest rates lead to an increase in the firm's financing cost | Changes in market conditions affect access to credit |

| Operational | Failures in operation by the company bring about failures to comply with service standards | Changes in external conditions directly affect the service | Acts of God and Force Majeure events affect service provision |

A further distinction can be made rearding exogenours distress: wether the causes of the problem are covered by the contract or not. Due to the impossibility of drafting a "complete" contract, certain situations that may take place during the contract's performance might not be contemplated therein. Therefore, it is necessary to determine ex-post among the parties to the contract the liability and distribution of the costs associated to these events.

To prevent these exogenous events not covered by the contract to give rise to conflicts and even to turn into a distress situation, a good contract management policy is required throughout the life of the contract.

Undoubtedly, each particular contract will determine which events may be included and which may not. The initial allocation of risks among the parties to the contract must be set at the design stage thereby reflecting the ability of each party to administer or control a specific risk. Consequently, in a pure price cap tariff regiem, the risk of a change in relative prices is contractually allocated to the service provider. On the other hand, in a cost of service regime, the risk is allocated to users.

The acts of god and force majeure events represent the typical example of exogenous events that are not contemplated in the contracts (and in general cannot be contemplated). Given the nature of such events, which are not foreseeable by definition, and if foreseeable cannot be avoided, they are not susceptible to be contemplated in contracts. Actually, the general legislation has, in many cases, prevented or restricted the possibility of taking out these risks.149

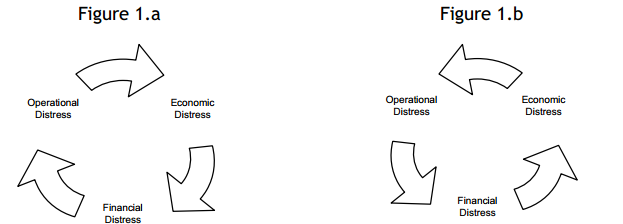

The proposed distinction basically serves analytical purposes, as the practical experiences show that these sources are not independent of one another. It also bears noting that, in general, the persistence of such sources over time causes the others to appear as well.

Thus, for instance, a situation of financial distress that causes the company to lose access to the capital markets may, if persistent over time, cause a situation of operational distress by frustrating the investments that are needed to maintain and expand the service. In turn, this would eventually end up producing a situation of economic distress by affecting the service, which can affect collectability and, therefore, the company's revenue (Figure 1.a).

It is also possible to find the reverse order of causality. A situation of operational distress that occurs as a consequence of a natural catastrophe may create conditions of declining collectability that will limit the company's access to the capital market to cover its working capital needs or refinance short-term debt maturities. This would end up in greater deterioration and the resulting economic distress (Figure 1.b).

Regardless of the original problem, it is necessary to intervene so as to prevent the problem from spreading and affecting the whole service (see BOX 33).

BOX 33: Economic crisis in a water company - Colombia

| In the district of Quibdó (Colombia), the water, sewage and sanitation services were performed by Empresas Públicas de Quibdó (EPQ). In January 2005, the Superintendency of Household Public Services (SSPD) took charge of the EPQ for liquidation purposes, due to its non-compliance with regulations and failure to make payroll payments and for the purpose of ensuring service continuity and avoiding negative impacts on public policy and the economy. During this process, the SSPD performed three main tasks: (i) It sustained service continuity; (ii) It started a process aimed at analyzing and identifying alternative long-term solutions; and (iii) It paid $1,066 million as late salaries to resume the service supply. Consequently, what started as an economic distress situation, caused by an extremely low collection rate, as it was not prevented on time, finally affected the operational and financial areas, thus affecting the provision, quality and expansion of the service. The scarcity of resources did not allow meeting the commercial, operating and labor debts. On the other hand, the late payment of salaries led to the interruption of the service due to a strike called by employees as a form of protest. |

The nature of PPPs entails the need to design, implement and maintain fluid communication mechanism between the public and private parties to follow the performance of the company. This will help to prevent and resolve distress situations to avoid that the possible detriment of one of the above-mentioned aspects escalates to a generalized collapse situation of the service. A key tool for this situation is the definition and monitoring of performance indicators for all relevant aspects of the service (in the three contemplated aspects: economic, financial and operating) together with the determination of thresholds upon which the implementation of corrective measures becomes necessary.

The existence of communication means and institutional instances in charge of the supervision of such situations of distress -such as a crisis committee- as soon as they are identified represents a key element. This facilitates the adoption of measures tended to minimize the impact of a possible negative shock on the set of PPP together with the resulting direct and indirect costs over the service and the economy as a whole.

Similar institutional arrangements are also necessary in many cases to efficiently solve certain problems or situations not contemplated in the contract such as those described in the third column of Table 26. Consultation mechanisms, mediations and other alternative dispute resolution methods may be used to settle those situations that have not been contemplated in the contract design and that may arise during its performance (creation or implementation).

To analyze the external factors that affect distress situations, it is convenient to draw an additional distinction between natural and political factors. Natural factors are those which, in general, are denoted by the concepts of act of God or force majeure. This means that, as we have mentioned before, they are events that cannot be foreseen or, even if foreseeable, cannot be avoided (acts of God). Given the non-controllable nature of such events, the costs thereof should not be borne by the company. Additionally, any actions taken in these cases should focus on mitigating the effects of the event on the service. Typical examples of these are the development and control of emergency and contingency plans for extraordinary natural events.

On the other hand, political factors are the result of government actions that directly or indirectly affect the conditions of service provision. These actions can be specific to the contract or sector (such as the imposition of additional obligations that were not provided for in the original agreements) or general in nature (an import prohibition that affects essential inputs).

Table 27 includes some examples of external - natural and political - causes that can bring about situations of economic, financial or operational distress.

Table 27: External causes of situations of distress

| External Distress | Natural | Political |

| Economic | Increases in input prices in domestic or international markets. | Declines in revenue as a result of the general crisis. Increases in input costs (e.g. salaries) due to government decisions |

| Financial | International financial crisis blocking access to markets | Financial crisis at the government level indirectly affecting the companies |

| Operational | "Acts of God" earthquakes, hurricanes, tornadoes, fires. | Wars, revolutions, terrorist action. Failures in the supply of inputs or access to natural sources. |

In practice, problems may occur either simultaneously or consecutively: a natural catastrophe is followed by an erroneous political response that leads to the deepening of the crisis (see BOX 34).

BOX 34: Electric Power Distribution Concession in Orissa

| In 1999, AES was awarded the concession of Central Electricity Supply Company (CESCO, Electric Power Distribution Company in eight districts of the Orissa coastal zone). Two months after taking possession of CESCO concession, a cyclone went over the state of Orissa and caused expensive infrastructure damage and casualties. Consequently, a major part of CESCO users were left without the service. The damage to the distribution infrastructure was estimated at 130 crores of rupees. However, AES alleged to have assumed losses for 300 crores of rupees (60 million dollars) as a consequence of the cyclone. The lack of infrastructure insurance and clear contractual provisions over the concessionaire's liability in cases of natural disasters led to a situation of great economic resources need in the framework of strong controversies with the regulator. It took CESCO more than a year and a half to fully re-establish the service. At this point, the distress process had adopted chronic features, resulting form two causes. The first reason, which had an endogenous nature, derived from the company's failure to reduce the levels of T&D Losses (AES could not reduce the indicator to 35%, the level set as a goal by Orissa Electricity Regulatory Commission OERC in the tariff determination). And the second reason, which had an exogenous nature, was associated to OERC's political decision that prevented CESCO from generating enough incentives on users to diminish the levels of T&D Losses which did not respond to technical causes. AES had requested a 25% increase in the electricity tariff and the possibility of collecting interest over default payments. Therefore, it could reach the economic equilibrium as well as attempt to reduce the non technical T&L Losses (by imposing an interest-bearing penalty). The OERC did not grant the increase and rejected the request to collect interest over default payments. At this point, AES had ceased paying the purchased electricity and thus OERC imposed a fine of 0,1 million rupees on it in June, 2001. That same month, the Managing Director of CESCO and representantive of AES resigned and AES finally abandonded the concession. |

There are two possible approaches to the analysis of situations of distress in PPP contracts: ex ante and ex post. The first approach - ex-ante - focuses on how the various types of distress that can affect a PPP contract can be prevented or avoided. This approach is directly related to the previous stages of analysis of the PPP cycle: PPP design, award mechanism, contract management and control and oversight at the construction and operation stages (see BOX 35 for ex-ante treatment of OFWAT's financial problems).

BOX 35: Preventing Financial Problems

| The tariff determination process that OFWAT concluded in 2004 found the water and sanitation sector of Great Britain with a particular financial profile. The development of investment plans required under the legislation in force, which were significantly expensive, caused the sector to face high investment rates for a long period of time. The result: negative cash-flows which called for the need of external resources. This gearing dynamics came to the attention of the OFWAT, which was afraid that the whole sector lost the investment grade rating, which would not only imply an infringement of the financial viability required by the regulator, but would also cause an increase in the cost of capital that the companies in the sector would have to deal with in the future. For the sake of avoiding the foregoing, the regulator decided to include the financiability payments to the tariff review process, focusing on the firm's financial ratios. It is then decided to resort to these "financiability payments" associated to the financial ratios of each company, in order to restore the investment grade rating among the companies. The determination of these payments followed a process aimed at defining, on an individual basis, whether the company could maintain a robust risk rating or not. The final determination resulted in granting financiability payments in the total amount of £430m during the 2005-2010 period. |

Two different approaches can be identified in this case as well. First, there are actions at the design and award stage that typically affect the contract structure (i.e. defining a formal, specific limit to the degree of leverage in order to avoid a situation of financial distress). Clearly, design aspects directly affect the political risks involved, even though they also produce important effects on the mechanisms for the resolution of distress situations originating in "natural" occurrences.

Second, actions at the construction and operation stages, where the structure has already been defined, focus on overseeing the behavior of the parties to the contract (i.e. under a general contract clause requiring prudent financial management, following up on the company's debt policy). The contract management strategy is also and important factor during the life cycle of the project to prevent and solve possible exogenous problems, not considered in the contract.

One key element to help manage an eventual distress situation is to develop, and implement contingency plans, which will help allocate responsibilities in the case of an emergency or crisis. In a sense, a contingency plan provides ex-ante with the elements to deal with the crisis ex-post.

The second approach - ex post - focuses, once a problem occurs, on identifying mechanisms to contain the problem, thereby preventing it from spreading to the other dimensions and becoming unmanageable, thus leading to the potential cancellation of the PPP.

In order to facilitate dealing with unforeseen situations, the contract should also have certain degree of flexibility built-in. This would give the possibility of looking for innovative and efficient solutions to problems as they arise without the need of renegotiating the contract.

Clearly, flexibility in the contract could give place to the risk of opportunistic behaviour by either party. Instead of working on a cooperative basis, the distress situation contract would be seen as an opportunity for extracting additional rents from the other. Building a good reputation by both parties and having in place a good governance system is therefore crucial to ensure the process is fair and importantly perceived as fair by all other stakeholders.

The main point of these mechanisms is that in their application, implementation and design, the sense of cooperation between the parties should prevail as it represents the essence of all PPP contracts. The adoption of a cooperative perspective by both parties leading to the resolution of conflicts and maximization of "Value for Money" of the project represents the main objective of the PPP adoption for the provision of services.

In this context, a renegotiation can be viewed as the lesser evil. In certain cases this can call for a modification of the existing contract to bring it in line with a permanent change in the conditions of service provision. Where the effects are temporary in nature, permanently amending the contract may prove unnecessary, and setting exceptional rules to apply under emergency conditions (such as a suspension of threshold quality requirements during a weather emergency) would be enough.

____________________________________________________________________________________

148 As opposed to accounting costs, economic costs include a normal return on invested capital.

149 In many legislations, when an event is defined as "force majeure", the parties to the contract are released from the contractual liability undertaken.