Instruments to Restore Equilibrium

The economic-equilibrium formula presented in the preceding section directly provides the set of instruments available to restore equilibrium in any situation in which such equilibrium has been altered.

On the revenue side, action is possible both on the level and on the structure of tariffs to correct the disequilibrium. Depending on the origin of the problem, the adaptation of the tariff structure may be a key action to mitigate the adverse impact of tariff level adjustments on the poorer, more vulnerable sectors of the population.

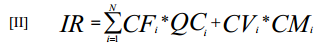

The required revenue (IR in formula I) can be broken down into tariffs (prices) and quantities consumed by each tariff category. Formally,

where: IR is the required revenue, CFi is the fixed charge for customer category i, QCi is the number of customers in category i, CVi is the variable charge for customer category I, and CMi is the average consumption for category i.

Adjustment on the revenue side can be performed such that only the tariff level is affected or, alternatively, such that the tariff structure is affected. Generally, structure adjustments combined with variations in the average tariff - tariff level - allow to better fulfill the various regulatory objectives (sustainability, allocative efficiency and equity. Thus, for instance, a tariff adjustment protecting the poorer strata of the population can prove to be a more efficient method to work out an economic distress problem without adversely affecting equality. This could keep the PPP from working out a problem at the expense of creating a new one - political in nature - by increasing the tariffs paid by the poorer strata of the population.

A change in the tariff structure increasing the fixed charge relative to the variable charges reduces the demand risk faced by the company and, consequently, may prove to be functional in helping mitigate a distress situation. However, this could impair the conditions of equity, since a higher fixed charge would cause the average tariff for those customers with lower consumption levels to increase relative to those with higher consumption levels. There are no magic solutions and the various alternatives should be carefully assessed, taking the potential trade-offs into consideration.

Transfers from (or to) the government are the second instrument available to affect the revenue (expenditure) of the company in order to restore the economic equilibrium of the contract.

If the transfer is made by the company to the government, the effect is the same even though the risk of interruption associated with a fiscal crisis is reduced. The company can withhold a portion of the transfer - upon express or implied permission by the government - to temporarily cover some economic gap associated with an external crisis157 (see BOX 41). In other words, because the government is associated to the project through a stake in its cash flow, it bears a portion of the costs generated by the distress situation.

BOX 41: Water concessions in Argentina

| At the beginning of the '90s, Argentina set forth a foreign exchange convertibility plan according to which the Argentine peso was pegged to the American dollar by a 1:1 parity. The concession of drinking water and sanitation services was awarded within this framework at a federal and provincial level, including, among others, Córboda and Santa Fe, where the same international group (SUEZ) was the successful bidder. In 1999 a profound economic and financial crisis broke out and led to the government's downfall and the repeal of the convertibility plan in 2002, which resulted in a significant depreciation of the local currency. Simultaneously, the utility tariffs were pesified and frozen and, due to the devaluation, the concessionaire's foreign debt service and the costs of tradable assets increased, thus causing the breakdown of the contracts' economic equilibrium. From that on, a long contractual renegotiation process began. The differences in contracts and the award mechanism explain the differences in the results of these two companies' renegotiations. The company in Santa Fe had been awarded on the basis of the lowest tariff offer for end users. In Cordoba, in turn, a bidding mechanism based on a formula with several elements had been applied, being one of the most important, the annual payments made to the government by the concessionaire. As a result, Aguas Cordobesas was paying about 25% of its revenue to the government as a concession fee. After long lasting negotiations, SUEZ group dropped the concession in Santa Fe and filed a suit against Argentina before the ICSID on the grounds of breach of contract. The concession in Córdoba was renegotiated and SUEZ sold its interest to a local group. If there are direct transfers between the government and the company under a PPP contract, the government is more willing to solve conflicts. In fact, it has clear incentives to be on good terms with the company and keep the concession ongoing, as it participates in its cash flow, thus avoiding long negotiation processes, which also end up affecting the service even more. Furthermore, this type of contract gives the government greater freedom to negotiate and an additional tool to address the crisis and restore the concessionaire's equilibrium, as it may always cancel the company's obligation to pay the fee so it may redirect said resources to cover the deficit generated by the crisis. |

In general, the existence of direct transfers between the government and the company in the context of a PPP contract provides greater leeway for a solution to potential situations of economic distress. If payment is made by the government to the company, the government can adjust the transfer in order to restore equilibrium in the short term without directly affecting service users. However, it should be kept in mind that, in the context of a fiscal crisis, any such transfer from the government often poses a risk, as it may be disrupted as a result of fiscal restrictions.

On the costs side the main instruments for restoring the equilibrium relate to investment levels and timing, elements affecting O&M costs (such as quality levels and service obligation targets) and contract duration and termination rules.

The amounts and timing of the investment are effective instruments to modify the equilibrium of the contract. Not only the amount of investment but also its timing matters to cash flows and hence to tariff levels needed to ensure the equilibrium.

Modifying service conditions affecting operation and maintenance costs is a second set of instruments available from the cost side to affect the economic equilibrium of the contract. A change in quality of service minimum standards following a crisis due to a natural disaster is a clear example of this. Given the high capital intensity of these sectors this instrument will be of limited effect as O&M costs usually have a relatively low incidence on total economic costs of the service.

The regulatory regime in many cases contemplates a price cap with automatic pass-through of some costs to users158. Under this regime, some of the costs, which are not under the control of the operator, are excluded from the cap formula. Any increase in these costs is automatically passed on to the users through a tariff adjustment. The adoption of this type of regime is generally justified by the existence of non-controllable costs by the operators combined with the need to introduce incentives. The more volatile or unpredictable these non-controllable costs are, the more important the need to adopt a regime that reduces the risks for the operator. The specific degree of pass-through defines how much of this uncertainty can be passed on to users.

Even though not stemming directly from the equilibrium equation formula, the modification of the rules for the pass-through of costs is yet another alternative instrument to modify economic equilibrium. To the extent that tariffs are adjusted to account for costs variations, the risk of such changes is shifted from the company to the end users.

In view of the long construction periods and of the long life and specificity of the assets in the infrastructure sectors, contract duration and termination rules are important instruments. Amortization and non-amortized investments at the end of the contract duration rules also affect the economic equilibrium. Unclear or unfavourable rules may suppress any incentive to invest too close to the end of the contract period. Adapting these rules, for example through an extension in the concession to compensate for unpredictable low demand, is an important instrument.

____________________________________________________________________________________

157 Of the three concessions held by the SUEZ group in Argentina, the Cordoba concession, which made provision for a payment by the company to the government, was the only one that was successfully renegotiated after the macroeconomic crisis that hit Argentina in 2001-2002. Following the renegotiation, Suez transferred its interest in Aguas Cordobesas to a local group. The other two concessions, namely Aguas Argentinas and Aguas de Santa Fe, which did not make provision for payments to the government, got cancelled and are currently the subject of international arbitration proceedings.

158 See Green Pardina 1997 for a discussion on pass-through mechanisms in price cap regimes and Tenenbaum … for applications to the energy sector.