PPP Regulatory Framework

The type of legal system (common law versus civil law) weighs heavily on the type of PPP regulatory framework that exists in a given economy. Economies with "common law" legal systems tend to rely on policy documents and administrative guidance materials, whereas economies with "civil law" legal systems are more likely to set up a detailed PPP framework in a binding legal document or statute or law, and to spell it out in detailed rules and regulations with legal force.

Even among economies with similar legal systems, there is a wide range in how PPPs are regulated. In part, this variation arises from the fact that PPPs are seldom regulated exclusively by a single legal document but rather by a set of legal instruments, including laws, regulations, decrees, enacted policies, and guidelines. Furthermore, other laws and regulations, although not exclusively focused on PPPs, might have an impact on them when regulating matters such as land ownership or public financial management. The regulatory framework for PPPs varies from one economy to another, depending on how all these elements are combined.15

From the analysis conducted, it is possible to devise a sort of typology of regulatory frameworks on the basis of how each economy has chosen to regulate PPPs. In addition to its illustrative and descriptive purpose, the presentation of this typology also helps better describe both the scope and some of the limitations of the analysis in the next sections of this report. Annex 1 provides an overview of the typologies of PPP regulatory frameworks adopted in the 82 economies analyzed.

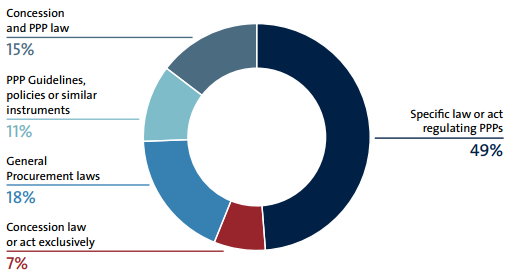

Almost half (49 percent) of the economies measured by Benchmarking PPP Procurement have adopted a law or act that specifically regulates PPPs (figure 3). In the sample of economies measured, this form is the most common way of establishing a regulatory framework for PPPs. Even within these economies, there is some heterogeneity in the coverage and name used (for example, the Philippines adopted a Build-Operate-Transfer [BOT] law rather than a PPP law) and even in the hierarchy of the adopted legal instrument (for example, Vietnam regulates PPP through an executive decree rather than a law). In addition, 7 percent of the economies (Cambodia, Chile, Costa Rica, Mongolia, Nicaragua, and Panama) have enacted only concession laws.

Figure 3 Type of PPP regulatory framework adopted (percentage, N = 82)

Note: PPP = public-private partnership.

Source: Benchmarking PPP Procurement 2017

In 15 percent of the economies surveyed, a PPP law coexists with a concession law. In 7 of those economies, the PPP law and the concession law are complementary. For example, in Argentina, the PPP law is supplemented by the concession law, which, in turn, is supplemented by the public procurement law. For those seven economies (Argentina, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Moldova, Poland, Tunisia, and Ukraine), a single analysis has been conducted attending to the provisions of both legal instruments as appropriate. In the other five economies (Brazil, France, Senegal, Togo, and the Russian Federation), however, our contributors expressly distinguished between two regimes, one for PPPs and one for concessions, according to specific features of the contract. For example, in Brazil, for PPPs the government remunerates the private partner for the availability of the infrastructure whereas concessions involve no government payment.16 In France, the differentiation depends on the risk transferred to the private sector, with concessions requiring the transfer of a proportion of the risk that involves real exposure to market fluctuations (but not completely excluding government payments).17 For these five economies, the analysis conducted for the Benchmarking PPP Procurement is disaggregated between concessions and PPPs, providing an understanding of the differences that both regimes entail.18

Instead of adopting a specific PPP or concession law, in 18 percent of the economies PPPs are governed by the general public procurement laws. In some of these economies, PPPs or concessions are specifically mentioned in the law or included as a specific type of contract (for example, the Dominican Republic includes in its public procurement law a specific section on concessions). Finally, 11 percent of the economies mainly regulate PPPs through guidelines, policies, or similar instruments (Australia, Canada, China, India, Jamaica, Malaysia, Singapore, South Africa, and Sri Lanka).19 Not surprisingly, this is mostly the case in common law economies. The distinction between alternative methods for regulating PPPs is sometimes blurry. For example, in the United Kingdom, a large number of provisions detailing the development of PPPs are contained in guidelines and policy documents, but the public procurement law also applies to the procurement procedure.

Closely related to the regulatory modality chosen to introduce PPPs in the regulatory framework, some economies impose restrictions on the sector in which PPPs may be used. In some of these cases, as in Chile, there is no formal restriction, but PPPs are not used in a number of sectors (electricity and telecommunications) that are operated completely by the private sector under the regulatory authority of the government. In other cases, private participation in the provision of infrastructure for specific sectors is regulated by the sectoral laws and regulations and is excluded from the application of the general PPP or concession law. This is the case in Colombia, for example, for telecommunications, ports, and public power-generating utilities. Finally, in a few economies, for some activities within an area, use of PPPs is restricted. In Uruguay, whereas the infrastructure for health and education centers can be delivered through PPPs, health services and education services cannot.20