Renegotiation or Modification of the PPP Contract

Given the long-term nature of PPP contracts, changes in circumstances underlying their execution are not uncommon. Although adjustment provisions provide the flexibility that a PPP contract may require as a result of unforeseen changes in circumstances, sometimes renegotiation may be the only avenue available to avoid a major disruption in contract execution. The term renegotiation refers to changes in the contractual provisions other than through an adjustment mechanism provided for in the contract.83 Renegotiation may have a positive impact when it addresses the intrinsically imperfect nature of PPP contracts.84 Nonetheless, to the extent possible, the use of renegotiation should be minimized, since it may become an opportunistic tool, leading to negative consequences.85 Finally, renegotiations may affect the contract in a way to render it materially different in character. In such cases, renegotiation should be precluded.

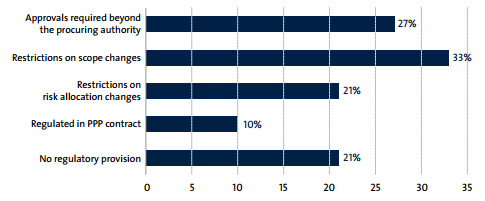

The economies measured have handled the issue of renegotiating PPP contracts differently (figure 18). Of the 82 economies, more than three quarters regulate, to some extent, the renegotiation or modification of PPP contracts. Despite the potential impact of this matter, regulatory frameworks in economies such as Algeria, Lebanon, Malawi, and Myanmar remain silent on it.86 Among the economies that address the renegotiation of PPP contracts in their regulatory framework, 10 percent consider it a contractual issue, leaving the parties to further regulate it in the contract. Such is the case, for example, in Benin, Turkey, and Zambia. In the remaining economies, some provisions are in place regarding PPP renegotiation. Among these particular provisions, there are requirements for specific approvals beyond the procuring authorities (27 percent of the economies), restrictions on changing the scope of the PPP contract (33 percent of the economies), and restrictions on changing the risk allocations of the PPP contract (21 percent of the economies).

Figure 18 Approach to address renegotiation of contracts (percentage, N = 82)

Note: PPP = public-private partnership.

Source: Benchmarking PPP Procurement 2017

Among the economies that require specific approvals by authorities other than the procuring authorities, such authorities range from general governmental entities, such as ministries of finance,87 treasury boards,88 and the cabinet,89 to specialized PPP agencies, such as the PPP technical committee in Tanzania and the National Committee for PPPs in Senegal.

When it comes to what amendments to the contract are allowed, Australia, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, France, the United Kingdom, and 11 other economies limit changes that affect the risk allocation of the PPP contract as well as other amendments that may be considered a "substantial" change.90 In the United Kingdom, for example, the regulatory framework specifies the conditions in which a change to the contract is deemed "substantial." The general rule is that if substantial modifications are made, a new procurement process may be required. However, in cases where the modification results from circumstances that the procuring authority could not have foreseen, does not change the overall nature of the contract, and increases the price by no more than 50 percent of the original contract value, then the modification is not deemed to require a new procurement procedure. The South African regulations also stipulate that the Treasury will approve a material amendment only if it is satisfied that the PPP agreement, if so amended, will continue to provide substantial technical, operational, and financial risk transfer to the private party.91