1.2 Privatisation and Public Private Partnership

Privatisation has been a common policy directive and development for Western governments (Broadbent and Laughlin 2004) for combating rising national budget deficits (Cavaliere and Scabrosetti 2008); increasing state revenues (Price Waterhouse in Megginson and Netter 2001); promoting the development of financial markets (Cavaliere and Scabrosetti 2008) and competitive behaviour (Fafaliou and Donaldson 2007); reducing government involvement in economic activity (Price Waterhouse in Megginson and Netter 2001); increasing efficiency (Cavaliere and Scabrosetti 2008); and fostering wider share ownership (Price Waterhouse in Megginson and Netter 2001) for investors.

In Australia, privatisation gained momentum during the early 1990s e.g. the part-privatisation of the Commonwealth Bank (Quiggin 2004) and the privatisation of Telstra (English 2006) as a way to tackle perceived public sector inefficiencies - it was heralded as a key microeconomic reform designed to "liberalise" the Australian economy (McKenzie 2008; Gray, Broadbent, and Lavender 2009). Coinciding with the emergence of privatisation, 'New Public Management' was championed as a means to modernise government and to bring its machinations in line with the principles of market-based competition in order to improve government and public administration practices (Diefenbach 2009; Groot and Budding 2008) and was seen as a refinement to earlier, less successful attempts at privatisation (International Monetary Fund 2004: p.4). A key element of privatisation has been the development of PPPs.

Although there is no all-encompassing definition for PPP (English 2008: p.2; Urio 2010: p.26), for this research it is characterised as a collaborative endeavour (Smyth and Edkins 2006) involving the public and private sectors, developed through the expertise of each partner in order to meet identified public needs through appropriate resource, risk and reward allocation (The Canadian Council for Public Private Partnerships 2009). These time and cost-specific ventures (English 2007) are normally constituted under long-term contractual arrangements (Infrastructure Australia 2008a: p.3) whereby the private partner agrees to build infrastructure (or engage in the provision of facilities or services) on behalf of the public sector (Lewis 2001) under specified terms and conditions (Grimsey and Lewis 2004: p.6) and for an agreed concession period. Characteristic of the latter has been a long-term (20 plus years) intent.

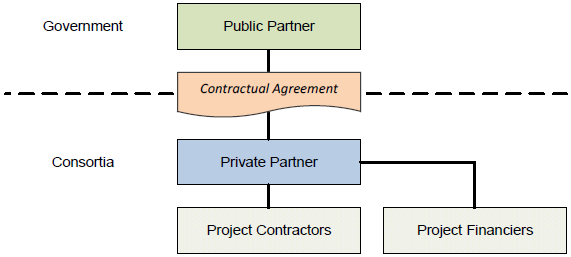

The private partner contracted in by government, known as 'consortia', typically consist of a group of commercially focused stakeholder organisations (Savas 2000: p.248) which include project financiers and project contractors. Fig. 1.1 below outlines a conventional PPP relationship structure.

Fig. 1.1 A Typical Relationship Structure Between Public and Private Partners in PPP.

From a public sector perspective, Value-for-Money (VfM) propositions that benefit communities through improved service delivery should be the primary focus of all PPPs (Sampath 2006). This concept of VfM is defined within an Australian state government context as "getting the best possible outcome at the lowest possible price" (New South Wales Treasury in English 2006) and means that public sector endeavours can be undertaken without increasing public borrowing or raising taxation levies (Osborne in Nisar 2007). The avoidance or minimisation of public debt remains a primary reason for Private Finance Initiative (PFI) projects (PFI is a term that can be used interchangeably with PPP (English 2008: p.2)) in the United Kingdom (UK), for example, where its absence from local authority balance sheets (or adherence to recommended limits) satisfies the stringent accountability demands of central government.

Other benefits of PPP include transferring service delivery (including service delivery risk) to consortia so that government can focus on delivering its core services to the community (Commonwealth Department of Administration and Finance 2006: p.2; Shen, Platten and Deng 2006) e.g. public health and education initiatives (Partnerships Victoria 2001a: p.5) whilst potentially obtaining large cost savings throughout project lifecycles (Commonwealth Department of Administration and Finance 2006: p.2). In practice, however, neither health nor education services provision has been entirely exempt from attempts at privatisation, and the 'core services' argument is thus substantially weakened; although the power / influence of health and education sector unions should not be underestimated in some countries e.g. the UK.

A more likely but less acknowledged benefit of using PPP might relate to political strategies to reign in public sector staffing expansion and cost as well as potential efficiencies derived from private sector technical and management expertise (Ahadzi and Bowles 2004; Asian Development Bank 2008: p.3-5). This latter point is a somewhat weak argument, since it is likely that, if the public sector were to retain responsibility for project delivery and operations, it would also employ suitably qualified and experienced personnel to do so. Thus the desire to contain public sector staffing costs (including the long-term future liability of funding employee benefits such as superannuation) is likely to be a compelling 'hidden' driver for PPP.

PPPs are also perceived by governments to be an attractive option due to the use of the 'payment for performance' principle, whereby payment by the public partner to its private partner is dependent upon the latter achieving specified (and hopefully enforceable) standards (Garvin and Bosso 2008). In other types of PPPs such as toll roads, the 'user pays' approach secures direct payment to the private partner in the form of toll charges or fares (subject to the accomplishment of investment and / or operational targets e.g. safety targets). These arrangements may be subject to royalty payments from the concessionaire to government, and making periodic increases in such charges (according to annual inflation rates or sector indexes) and fares subject to the final approval of government.

Although this method of procurement is seen to be effective and desirable by its supporters, it is not without criticism. Failures can result (in the case of Economic Infrastructure projects, for example) from poor allocation of risk (The Asian Development Bank 2008: p.2), sub-standard contract design and inadequate bid criteria leading to underinvestment by consortia which may culminate in inefficient service user charges and the exposure of taxpayers to unintended project risks, whilst shifting profits to project "promoters" (Ergas 2009). Human factors such as an insufficient skill base and poor relationship management can also lead to project failures (Yuan et al 2009; Koppenjan 2005). None of this is intended to argue that PPP failure is predominantly attributable to drafting, documentation and management shortcomings on the part of the public partner. There is little evidence for that. However, all these aspects place a substantial burden on the public partner in the procurement, delivery and operational phases of PPP projects which, if not effectively managed, can impact upon the achievement of VfM outcomes.