4.3.2 Theoretical Frameworks

PPP procurement purports to include risk-sharing principles (through the clear allocation of risk between public and private partners). For the public partner, there are risks involved in operational governance / administration during long-term concession arrangements. Therefore, the theory of risk management is necessary for identifying what principles, processes and issues might arise for PPP projects. Understanding this places the development of an integrated management model on a firm theoretical base.

As part of the human condition, people are driven to improve the way in which they live (Renn in Bouder, Slavin and Lofstedt 2009: p.15). To achieve our wants and needs, we often have to make decisions that involve taking risks. Therefore, risk-taking arises from a desire to make purposeful change in our lives, and that in pursuing our desires, there will be consequences to our actions; some may be intended (or tolerated) whilst others will be unintended. However, consequences can actually outweigh the benefits of taking risks. Renn (in Bouder, Slavin and Lofstedt 2009: p.15) says that risk assessment can be undertaken (typically balancing likelihood and consequence as well as risk and reward) to judge the acceptability (i.e. tolerability) of risks before embarking upon a course of action. Risk management can then be used to prevent, lessen or modify the likelihood of occurrence of the risk event or its consequences by selecting the most appropriate option. Thus, the application of risk assessment and risk management can influence our desires: it may lead to alternatives or allow a greater degree of control to be applied to certain aspects of the risk, that then makes risk targets less vulnerable to potential harm (Renn in Bouder, Slavin and Lofstedt 2009: p.15-16). This builds upon the notion that risk is subject to the belief that human action can prevent or at least mitigate harm from occurring (Renn in Bouder, Slavin and Lofstedt 2009: p.21).

However, risks are social phenomena - they are constructs that are developed in the minds of individuals (Renn in Bouder, Slavin and Lofstedt 2009: p.21). These structures are built from our observations and experiences, and people therefore have the capacity to create different scenarios and futures. Risk is not only experienced individually, it also occurs collectively in groups and by society more generally. Risk is therefore a social construct. Different perceptions that make up diverse communities can lead to complexity as stakeholder groups may form different views of what the risks are (to them) and likewise, how they should be managed (Renn in Bouder, Slavin and Lofstedt 2009: p.16-17). Moreover, people must consider organisational and institutional capabilities, including available resources and the opportunity cost of implementing risk management plans. Political and cultural norms, rules and values should also be considered (Renn in Bouder, Slavin and Lofstedt 2009: p.16-17).

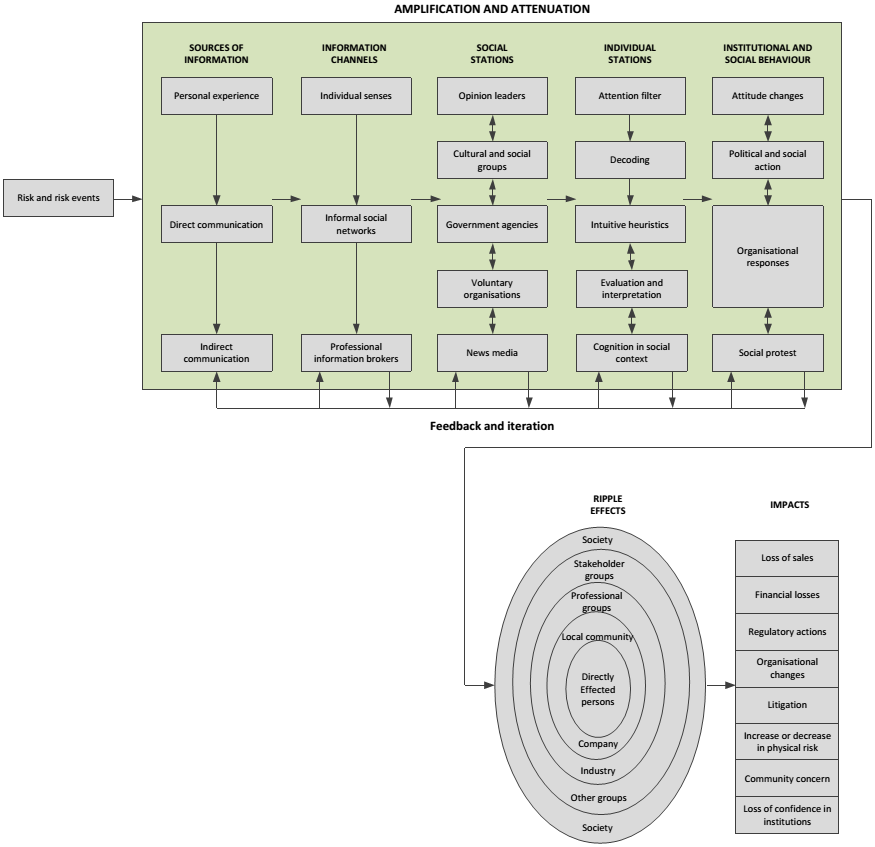

Communication is thus vital in representing differing views of what constitutes risk: if risk perceptions are not seen or heard they cannot easily be understood. Kasperson et al (1988) offers a conceptual framework, the 'Social Amplification of Risk Framework', to explain the relationship between hazards and the psychological, sociological, cultural and organisational processes that may amplify or ease public concerns to risks. This is important because, according to Kasperson et al (1988), stakeholder groups have competing views and each will want to shape public reaction in line with its own perceptions and desired outcomes. Stakeholders can assert their influence, for instance through power of persuasion, through an in-depth understanding of particular risks and expertise in risk management.

This 'social amplification' of risk can be represented diagrammatically in Fig. 4.2.

Copyright © 2006, John Wiley and Sons.

Fig. 4.2 The Social Amplification of Risk Framework (Source: adapted from Kasperson 1988).

Although Fig. 4.2 excludes mention of 'signals', there is a direct relationship between sources of risk and signals (Kasperson et al 1988). A risk source is where the risk originates from and where signals are used to form messages which are transmitted to or received through communications channels. These include personal networks, politicians, governments, the media, etc (Kasperson et al (in Slovic 2010: p.318)). It is from these messages that Kasperson et al (1988) claim that our awareness of risk is triggered. Social amplification of risk represents the phenomenon by which information processes of risk, risk events and management systems influence the experiences of individuals and groups.

Amplifications can potentially produce secondary social and political impacts which will then create third order impacts, and so on. These types of impacts may arise from legislation, litigation, community opposition, investor attitudes, etc (Kasperson et al in Slovic 2010: p.319-320)). The degree to which this ripple-effect occurs depends upon the level of social learning and interaction that stems from experience with particular risks. Ripples have the potential to spread to previously unrelated technologies or institutions depending on how effectively risks are communicated and how well they resonate with people (Kasperson et al in Slovic 2010: p.319-320).

Direct experience can provide an understanding of the nature, extent and manageability of hazards which may lead to a greater capability of avoiding (or managing or taking) risks (Kasperson et al 1988). In other words, not only can experience act as a risk amplifier, it can also serve to mitigate them - or at least inform the mitigation process. However, as already implied, not all risks are experienced directly. This is why risk messages that are transmitted or received through communication mechanisms can have a considerable effect on influencing public responses to risks, thus acting as a major agent of amplification. The validation of perception is more likely to occur through personal (or professional) networks whereas the interpretation and response to information that flows from social, institutional and cultural contexts are more likely to come from the media or other sophisticated platforms that have considerable reach (Kasperson et al 1988).

The 'Risk Governance Framework' is an analytic framework that can be used to develop in-depth assessment and management strategies for handling risks. This framework integrates scientific, economic, social and cultural characteristics to help make decisions about what should constitute 'risk' (Bouder, Slavin and Lofstedt 2009: p.5). Moreover, it takes into account different stakeholder perspectives that may require co-ordination and even reconciliation between the roles, outlooks, goals and / or actions of those involved (Bouder, Slavin and Lofstedt 2009: p.5) as well as providing the more common elements of risk assessment, risk management and risk communication (Renn in Bouder, Slavin and Lofstedt 2009: p.7).

Another feature of the 'Risk Governance Framework' is that it offers a classification for risks based upon how difficult they may be to manage and how much is known about them, using the following categorisations - simple, complex, uncertain and ambiguous (Renn in Bouder, Slavin and Lofstedt 2009: p.7). However, it should be noted that the latter two groupings, i.e. uncertain and ambiguous, are similar in nature and the categorisations exclude the likelihood that some risks may be almost certain to occur. Renn (in Bouder, Slavin and Lofstedt 2009: p.7) states that risks should be classified according to how difficult it is to establish a cause-effect relationship between 'risk agents' and the consequences of the risks being realised, the degree of certainty in the cause-effect relationship, and the level of controversy / meaning that risk realisation will have on those who are likely to be impacted.

The major components of this Framework are 'pre-assessment', 'risk appraisal', 'tolerability and acceptability judgement', 'risk management' and 'communication'. Each is discussed in turn and represented in Fig. 4.3, below.

[Image removed due to copyright restrictions]

Fig. 4.3 The Risk Governance Framework (Source: Renn in Bouder, Slavin and Lofstedt 2009).

- Pre-assessment (Renn in Bouder, Slavin and Lofstedt 2009: p.9-10). This involves capturing the issues that stakeholders and society have about particular risks including identifying the factors that have led to the formation of these perceptions. This involves 'framing' risks so that a common understanding of them is developed between all risk participants; establishing early warning and monitoring mechanisms to indicate whether risk signals indicate their realisation; pre-screening to conduct preliminary probes into hazards / risks (that are based on priorities and the use of existing models for dealing with risks); and selecting the main assumptions, principles and procedures for assessing risks and emotions associated with them.

- Risk appraisal (Renn in Bouder, Slavin and Lofstedt 2009: p.10). This component is about providing a suitable knowledge base for which societal decisions can be made on whether or not to take risks and how they should then be managed. This involves a scientific assessment of risk and its social and economic implications (a concern assessment) with an aim of linking the risk source with its potential consequences. There are three main challenges associated with this component; 'complexity', 'uncertainty' and 'ambiguity'. Successful outcomes, Renn asserts, depend upon the transparency of the implications during risk assessment as well as throughout all subsequent phases when applying this Framework.

- Tolerability and acceptability judgement (Renn in Bouder, Slavin and Lofstedt 2009: p.10-11). This requires the characterisation and evaluation of risks to determine their acceptability and / or tolerability by assessing the broader value-based issues that also influence how the judgement is made. Risks that tend to be judged as acceptable are limited to those that have negative consequences and can potentially be taken on without control or treatment actions being put in place, whereas risks deemed to be tolerable have some positive connotations. In these cases, controls and / or treatments are used to mitigate potentially adverse consequences from arising that may prevent the benefits from being realised.

- Risk management (Renn in Bouder, Slavin and Lofstedt 2009: p.11-12). This involves the development and implementation of controls and treatment actions to best manage those risks. Factors to consider during decision-making that lead to implementation include the information derived from the pre-assessment, risk appraisal, and tolerability and acceptance judgement phases which can then be assessed against a range of other criteria such as efficiency, effectiveness, cost, sustainability, etc. The results from this assessment are then informed by a value judgement against each assessment measure. After implementation, it is important to institute a regular program of monitoring and review to make necessary adjustments to performance.

Renn notes that the dominant attribute of each of the four risk categories i.e. 'simple', 'complex', 'uncertain' and 'ambiguous' should lead to the identification of a specific strategy for managing the risk. Simple risks can be dealt with by using routine, traditional or best practice decision-making methods, as well as by trial and error. Complex and uncertain risks are differentiated by strategies that deal with 'risk agents' on one side and those that are precaution-based and resilience-focussed, on the other. Ambiguous risks rely upon strategies that create tolerance and shared understanding of divergent perspectives and values that should aim ultimately to resolve these differences.

- Communication (Renn in Bouder, Slavin and Lofstedt 2009: p.13-14). A critical component of the Risk Governance Framework, communication is central to the overall effectiveness particularly with regard to identifying and understanding others' viewpoints, pinpointing options and managing risks. Risk communication can also promote tolerance for conflicting standpoints, provide a foundation for their resolution and lead to trust amongst stakeholder groups.

These frameworks demonstrate that risk perceptions about PPP need to be managed within a communicable framework. The ISO 31000 (2009), as stated, is the preferred risk management guidance document for this research. It places a heavy emphasis upon communication.

In addition, ISO 31000 (2009) encompasses all types of operating risks encountered in PPPs e.g. contract variation, contract termination, concession hand-over, etc that need to be managed by the public partner. It is broad enough to encompass risk management plans and risk registers that can be tailored to meet specific needs (ISO 31000 2009: p.1) throughout the operational phase of PPPs. Thus, ISO 31000 (2009) can be a useful tool for public partner use to increase the likelihood of achieving PPP objectives by heightening the awareness of the need to identify and actively manage risks using a process-driven approach.

This research assumes, however, that the most significant stages for identifying threat and opportunity risks are negotiated and built into PPP agreements during design and tender (National Audit Office 2003: p.9) periods (i.e. the procurement phase) and that with anticipated VfM achievement or economies of scale, this will perhaps be a legitimate reason (there could be many others) for awarding a contract to a particular bidder. It is also assumed that there may only be a limited amount of scope for further opportunity risk identification during the operational phase e.g. through potential skill and technology transfers (Baker and McKenzie Solicitors 2006: Annexure N). Opportunity risk identification is also usually accompanied by limited capacity for exploitation. Even if opportunity risks are identified during operations, the potential for risk realisation will likely be tempered with incentive levels as set out under concession deeds as well as risk appetite for taking on additional risk (balancing the principles of 'risk' and 'reward').

Nonetheless, from a public sector perspective, risk management can be beneficial for standardising training opportunities and sharing knowledge across government departments and / or agencies (Department of Treasury and Finance 2007b: p.4), derived through real experiences of managing performance risk, by drawing on specific instances of under-performance in situations where different decisions could have led to better results.

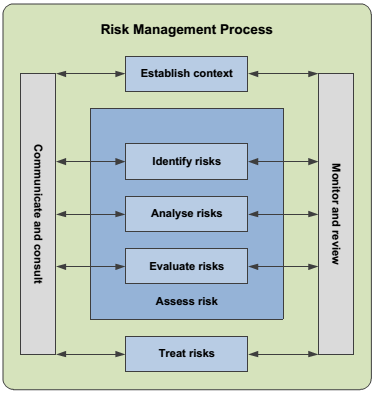

The risk management process is illustrated below in Fig. 4.4 and comprises the following elements:

AS/NZS ISO 31000:2009 Figure 3 - Reproduced with permission from SAI Global Ltd under Licence 1410-c054.

Fig. 4.4 A Model for Risk Management (Source: AS/NZS ISO 31000: 2009).

- Establishing the context (ISO 2009: p.15). This involves defining objectives and setting limitations i.e. the boundaries for managing the risk, as well as setting the scope and criteria for the remaining process e.g. aligning PPP objectives with its operational scale, structure and delivery arrangements. It also involves recognising the specific drivers (technical, physical, economic and social conditions and circumstances) that are likely to 'shape' the risks, i.e. affect assessments of the likelihood of occurrence of risk events and the nature and potential magnitude of their consequences.

- Risk assessment (ISO 2009: p.17). Risk assessment comprises the overall process of risk identification, risk analysis and risk evaluation (see below).

o Risk identification (ISO 2009: p.17). This process is about recognising risk; its impacts, events, causes and potential consequences. Appropriate risk identification tools and techniques should be applied and may include the assembly and examination of precedent risk management documentation such as contractual deeds, risk registers, risk profiles and organisational records that have been used in similar PPPs relating to planning or operational policy.

o Risk analysis (ISO 2009: p.18). Analysis involves understanding the risks to provide an input into risk evaluation and into decisions involving risk treatments. This part of the process involves examining the causes and sources of risks, defined by its consequences (the outcome of the event, described in terms of its impact on the achievement of objectives e.g. VfM) and likelihood (the chance of 'something' happening) of the risk occurring e.g. operator performance may not be reviewed as rigorously or in the same way by a new public partner employee after the retirement of a highly experienced contract manager. This may lead to a permanent loss of corporate memory due to a lack of succession planning, thus impacting on the attainment of VfM.

o Risk evaluation (ISO 2009: p.18). Risk evaluation assists with decision-making that is based upon the outcomes of the risk analysis stage and involves comparison between risk levels determined at the analysis step with risk criteria established when the context was considered and includes formulating potential risk treatments. In this process, risks may be strategically prioritised in terms of their comparative severity.

- Risk treatment (ISO 2009: p.18-19). This focuses on selecting the best option for modifying risk and the implementation of controls to manage the risks. Risk treatment can be described as a cyclical process of assessing treatments; deciding if further action is necessary to mitigate the existing levels of risk; and implementing new controls, if deemed necessary e.g. with regard to the example provided for 'Risk analysis', controls could include the design and implementation of co-ordinated succession plans for key roles and developing minimum standards for document management.

- Monitoring and review (ISO 2009: p.20). Monitoring and reviewing risks should form an integral part of the process and ideally involve regular scrutiny - particularly in relation to the changing perception of risks and their controls, lessons learned from actual events and trends e.g. adding emerging risks to risk registers or modifying existing risks due to consistent and sizable decreases in service user volumes in Economic Infrastructure PPPs.

- Communication and consultation (ISO 2009: p.14). This should take place between partners during all stages of the risk management process and include matters such as the risk itself, underlying causes, consequences and risk treatment actions. Communication and consultation should also extend to providing stakeholders with an understanding of why particular decisions and actions should be taken e.g. testing and finalising contingency plans due to the possibility of major default by consortia.

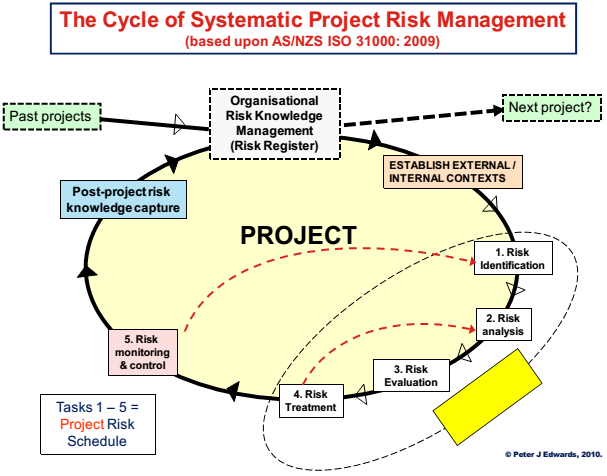

According to Edwards and Bowen (2005: p.97), these stages are better represented as a flow diagram (as illustrated below in Fig. 4.5) using a cyclical loop to show continuous learning and improvement (facilitated by knowledge capture) between projects or between project phases.

Reprinted with permission of Edwards and Bowen. Copyright © 2005.

Fig. 4.5 A Cyclical Model for Risk Management (adapted from Edwards and Bowen, 2005).

This loop, they claim, is particularly important during the monitoring and review stage as this is when new risks are typically identified or the circumstances of known risks change (Edwards and Bowen 2005: p.98). They also note the importance of post-project risk knowledge capture; an aspect not dealt with in the risk management processes reflected in ISO 31000.