4.4.2 Theoretical Frameworks

Performance management' is usually understood as an intra-organisational requirement associated with the achievement of stated objectives, and in some instances, competitive benchmarking. It is therefore important to identify if the principles, processes and issues of performance management theory are applicable to the private partner's performance in delivering agreed services under PPP arrangements. Understanding this places the development of an integrated management model on a firm theoretical base.

'The Balanced Scorecard' approach, advocated by Kaplan and Norton (1996), can be applied to translate the aims, values and strategies of an organisation into a well-defined set of performance measures. These measures can be used as a framework for strategic management purposes that drive operational performance. The measures developed using this approach extend both to external factors e.g. stakeholders and internal factors e.g. critical processes and employee learning and growth. They are balanced between an organisation's historical efforts and what decision-makers hope to achieve in the future. Also integral to the Scorecard is the development of a blend of outcome measures (lagging indicators) and performance drivers (leading indicators) (Kaplan and Norton 1996: p.31). Some of these will be objective (and simple to quantify) and subjective (often harder to evaluate and based upon personal judgement e.g. the extent to which 'value' has been achieved) (Kaplan and Norton 1996: p.10).

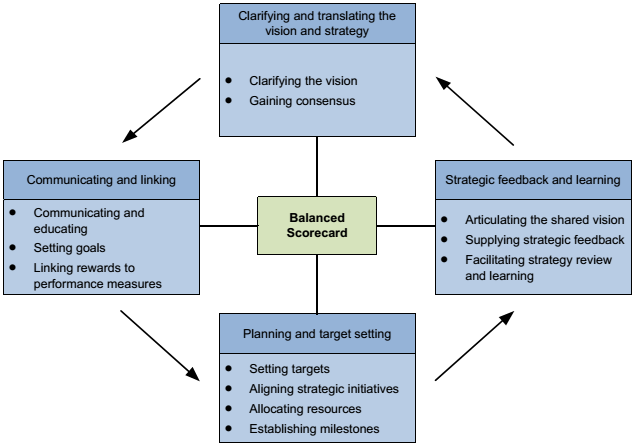

Kaplan and Norton (1996) claim that the Balanced Scorecard approach will assist decision-makers to clarify and translate vision and strategy; communicate and link strategic objectives and measures; plan, set targets and align strategic initiatives; and enhance strategic feedback and learning. An outline of each is provided below and is illustrated in Fig. 4.6:

Reprinted with permission from "Translating Strategy into Action: The Balanced Scorecard " by Kaplan, R.S., Norton, D.P. Copyright © 1996 by the Harvard Business School Press; all rights reserved.

Fig. 4.6 The Balanced Scorecard as a Strategic Framework for Action (Source: Kaplan and Norton 1996).

- Clarify and translate vision and strategy (Kaplan and Norton 1996: p.10). At the highest level, this process involves the senior management group deciding upon and interpreting organisational strategy into specific strategic objectives and measures.

- Communicate and link strategic objectives and measures (Kaplan and Norton 1996: p.12-13). The objectives and measures must then be communicated to employees and other stakeholders, as appropriate. Communication should be used as a signal for transmitting the message that for the strategy to succeed, the objectives must first be met.

- Plan, set targets and align strategic initiatives (Kaplan and Norton 1996: p.13). The authors state that the Balanced Scorecard is most effective when it is used to drive organisational change. Therefore the senior management group should develop targets for the medium-term (between three and five years) to give sufficient time to transform the organisation (however short-term targets should also be considered depending on how responsive the organisation has to be towards its stakeholder attitudes / current operating environment).

- Enhance strategic feedback and learning (Kaplan and Norton 1996: p.15). The Balanced Scorecard allows the senior management group to monitor and modify the implementation of their strategy or make more significant changes to it, if necessary. This may have knock-on effects in terms of communicating changes to staff (or stakeholders more generally), (re)educating them and motivating them.

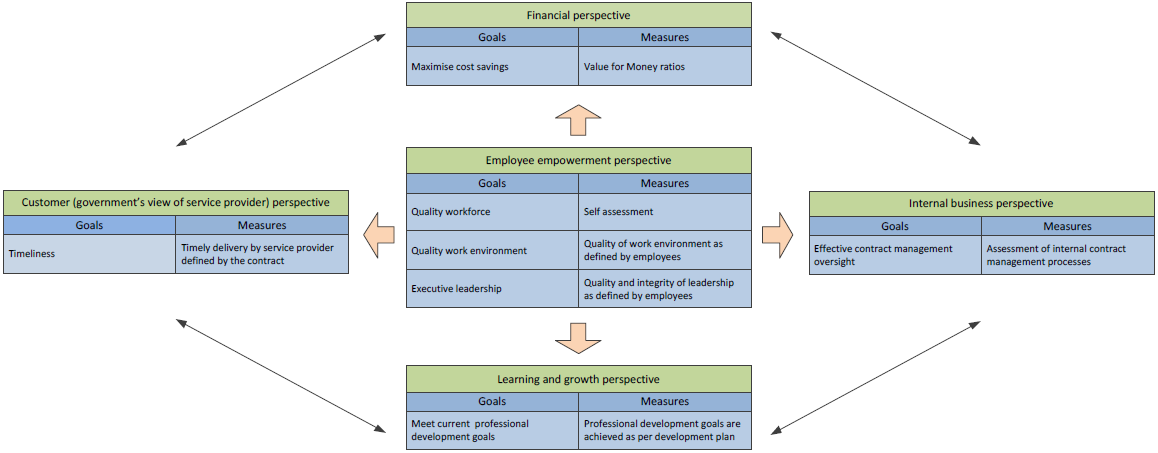

The Balanced Scorecard can therefore assist decision-makers to measure their organisation's value creation and how they can improve internal capabilities and investment in people, systems and procedures that lead to better performance (Kaplan and Norton 1996: p.8). It also enables senior executives to oversee short-term performance (via financial results) whilst simultaneously monitoring the organisation's progress in developing its longer-term capabilities (Kaplan and Norton 1996: p.8). In doing so, the Scorecard measures organisational performance across a range of balanced perspectives - financial, customer, internal business processes, learning and growth, and employee empowerment. These components are illustrated below in Fig. 4.7 (using a limited number of hypothetical examples for the public partner in PPP) and comprise the following:

Reprinted with permission from "Translating Strategy into Action: The Balanced Scorecard " by Kaplan, R.S., Norton, D.P. Copyright © 1996 by the Harvard Business School Press; all rights reserved.

Fig. 4.7 The Balanced Scorecard for the Federal Procurement System (adapted from Kaplan and Norton 1996).

- Financial perspective. This involves linking an organisation's financial objectives to its corporate strategy in order to improve its financial performance. Typically, these objectives underpin the objectives and measures contained in each of the other Scorecard perspectives (Kaplan and Norton 1996: p.47).

In context of government, Kaplan and Norton (1996: p.180) claim that the financial perspective will rarely be the primary objective (this assertion, however, is difficult to reconcile as price / cost is undoubtedly a key factor in determining VfM propositions for PPP - see '3.4 Public Private Partnership' for 'VfM' definitions). Depending on circumstances, financial objectives for the public partner can be regarded either as enablers or constraints within which the government must operate (Niven 2003: p.34), with respect to delivering intended social outcomes through PPP mechanisms.

- Customer perspective. This perspective of the Balanced Scorecard for a commercial firm is about deciding which customer groups and market segments it wishes to compete for and then aligning customer outcome measures with its financial measures for revenue generating purposes (Kaplan and Norton 1996: p.63). According to Niven (2003: p.33-34), defining who 'customers' are for government can be "perplexing" due to a wide array of interested parties that seek to influence or gain from public sector decision-making. In context of PPP, government can be viewed as the 'customer-by-proxy' in terms of service delivery arrangements secured and rendered on behalf of the state - however it is acknowledged that end users (for example) are intended beneficiaries of these services. The public partner therefore acts as an agent on behalf of certain stakeholder interests in pursuing VfM outcomes for them. These propositions characterise the drivers and lead indicators for designing the customer outcome measures (Kaplan and Norton 1996: p.63).

- Internal business process perspective. This is about identifying the processes that are vital for realising customer / stakeholder objectives (Kaplan and Norton 1996: p.92). These objectives and measures are normally designed after the financial and customer perspectives have been completed. Developing them in this order enables the senior management group to focus their business process metrics on the "complete internal process value chain" to identify current and future stakeholder needs as well as service delivery improvements (Kaplan and Norton 1996: p.92).

- Learning and growth perspective. The objectives that are established in the perspectives above form the basis for identifying what the organisation must do to achieve "breakthrough" performance (Kaplan and Norton 1996: p.126). Learning and growth objectives provide the means to support the achievement of the other perspectives' objectives. As government is focussed on attaining positive social outcomes, it can be heavily reliant upon the skills and commitment of its employees (and the tools they use) to deliver its goals (Niven 2003: p.35).

- Employee empowerment perspective. Kaplan and Norton (1996: p.136) assert that employees, even those who are highly skilled and have access to the information they need to do the job well, may not fully contribute to organisational success if they are not motivated to act in its best interests or if they are not given sufficient autonomy to make decisions and take actions (not being provided with the right resources could be another reason). Section '4.2.3 Partnership Management Principles' provides examples of how these types of factors can impact upon public partner employees including the sorts of challenges they may face during PPP operations.

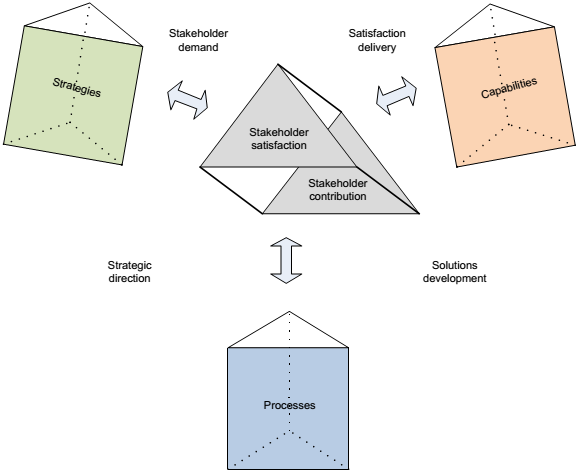

A second framework that can be used by government is 'The Performance Prism'. This is a flexible framework that has been deliberately designed to manage one or more components of an organisation's performance, which can be applied for instance, to multi-stakeholder group interests or an individual business process (Neely, Adams and Kennerley 2002: p.160). The Performance Prism can be used to identify the key elements of strategies, processes and capabilities and then for developing an appropriate measurement system to satisfy stakeholder and organisational requirements (Neely, Adams and Kennerley 2002).

According to Neely, Adams and Kennerley (2002: p.181), in order to fully understand 'performance', it is necessary to view its numerous and inter-connected perspectives. This is possible, they say, through the application of The Performance Prism. This framework consists of five inter-linked performance perspectives - Stakeholder satisfaction, Stakeholder contribution, Strategies, Processes and Capabilities. Each is summarised below under Fig. 4.8:

"The Performance Prism: The Scorecard for Measuring and Managing Business Success", Neely, Adams and Kennerley. © Pearson Education Limited 2002.

Fig. 4.8 The Performance Prism (Source: Neely, Adams and Kennerley 2002).

- Stakeholder satisfaction. The senior management group must decide which stakeholder wants and needs will be represented. Thus, the foundation for deciding what to measure is based upon identifying who the organisation's stakeholders are and ascertaining their requirements.

- Stakeholder contribution. The authors stress this perspective is subtly different to 'stakeholder satisfaction'. It is distinctive in the realisation that not all customers / stakeholders have a desire or need to be loyal or profitable. Instead, they may be more interested in, for example, purchasing superior services at an equitable price and obtaining a sense of satisfaction from the services that they use. It is the organisation, they say, that ought to be concerned about issues such as loyalty (presumably for long-term profitability reasons for commercially-driven firms and the achievement of VfM outcomes for governments). Neely, Adams and Kennerley (2002) claim that by developing a sound understanding of the "dynamic tension" that exists between customers / stakeholders and the organisation - in this case, an understanding by the public partner of its private partner's intentions, motives and operational challenges - it can be useful in developing or modifying its performance management system for assessing service delivery performance.

- Strategies. Neely, Adams and Kennerley (2002) claim that the majority of performance measurement systems wrongly begin at the strategy definition stage. The essential component of this perspective is to adopt strategies that accord best with stakeholder satisfaction and contribution. This involves developing a set of measures so that contract managers can monitor whether strategy implementation is actually being achieved in practice, use the measures to communicate the strategy throughout the organisation, applying the measures in a way that encourages and motivates the execution of the strategy, as well as analysing data to determine whether or not the strategy is being delivered as expected (and for the senior management team to make any necessary modifications to the strategy).

- Processes. With regard to developing organisational processes, Neely, Adams and Kennerley (2002) assert that five aspects / features should be taken into consideration. The first is 'quality': this involves measuring consistency, reliability, and accuracy, etc. Second is 'quantity' which consists of volume, throughput and completeness. The third aspect is 'time' which can involve measuring factors such as availability and timeliness. Fourth is 'ease of use' and comprises flexibility, convenience, accessibility, etc. The fifth aspect relates to 'money' - cost, price and value. Many of these measures can be used by the public partner when monitoring the performance of PPP service providers; and the resulting data used as a basis for applying penalties or abatement for service under-performance.

- Capabilities. Capability means bringing together an organisation's employees, practices, technology and supporting infrastructure to meet the needs of stakeholders (as described above). For PPP, for example, this may mean the achievement of government objectives i.e. the delivery of VfM outcomes through efficient and effective contract management.