Executive Summary

Governments around the world have turned to public-private partnerships (PPPs) to design, finance, build, and operate infrastructure projects. Government capabilities to prepare, procure, and manage such projects are important to ensure that the expected efficiency gains are achieved.

Procuring Infrastructure PPPs 2018 assesses the regulatory frameworks and recognized good practices that govern PPP procurement across 135 economies, with the aim of helping countries improve the governance and quality of PPP projects. It also helps fill the private sector's need for high-quality information to become a partner in a PPP project and finance infrastructure. Procuring Infrastructure PPPs 2018 builds on the success of the previous edition, Benchmarking PPP Procurement 2017, refining the methodology and scope based on guidance from experts around the world, as well as expanding its geographical coverage.

The report is organized according to the three main stages of the PPP project cycle: preparation, procurement, and contract management of PPPs. It also examines a fourth area: the management of unsolicited proposals (USPs). Using a highway transport project as a guiding example to ensure cross-comparability, the report analyzes national regulatory frameworks and presents a picture of the procurement landscape at the beginning of June 2017.

Several trends emerge from the data.

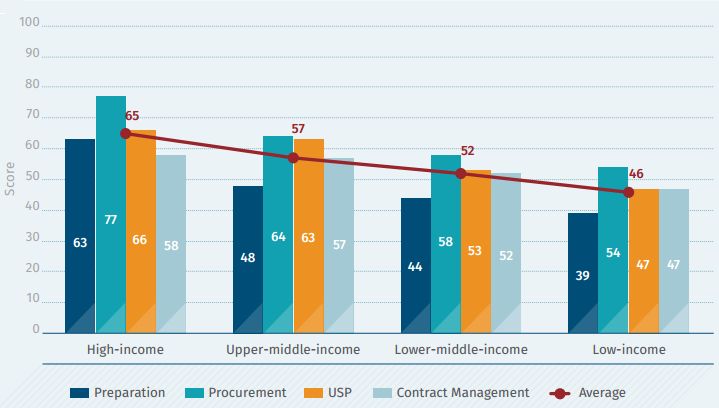

The higher the income level of the group, the higher the performance in the assessed thematic areas. Preparation and contract management are the areas that have the most room for improvement across all income level groups (Figure ES1).

Performance varies greatly by region. The high-income economies of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the Latin American and Caribbean regions perform at or above the average in all thematic areas. In contrast, Sub-Saharan Africa and the East Asia and Pacific region have the lowest average scores across thematic areas.

Contrary to popular perception, stand-alone PPP laws are not significantly more frequent in civil law countries than in common law countries. While 72 percent of civil law economies surveyed had stand-alone laws, 69 percent of common law countries did, as well.

However, there are some interesting regulatory trends across regions. The majority of OECD high-income countries regulate PPPs as part of their general procurement law. Europe and Central Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean have the largest proportion of economies adopting stand-alone PPP laws. Meanwhile, the Latin America and Caribbean region has undergone two waves of regulatory reforms: first by adopting concessions laws in the 1980s and 1990s on a large scale, and more recently through an ongoing series of PPP reforms.

The creation of PPP units is a common trend to support the development of PPPs. As many as 81 percent of the assessed economies have a dedicated PPP unit, which, in most economies, concentrates on promoting and facilitating PPPs. In 4 percent of the economies, however, the PPP unit takes a prominent role in the development of PPPs and acts as the main (or exclusive) procuring authority.

Figure ES1 Procuring Infrastructure PPPs 2018 average scores by income group (score 1-100)

Source: Procuring Infrastructure Public-Private Partnerships 2018.

Note: USP = unsolicited proposal.

Despite the importance of an appropriate consideration of the fiscal implications of PPPs, this is still an uncommon practice. During the preparation of PPPs, the approval by the Ministry of Finance to ensure fiscal sustainability is not required in 19 percent of the surveyed economies. Moreover, only around one-third of the economies have regulations concerning the accounting and/or reporting of PPPs, and even fewer have introduced some type of regulatory provision regarding the budgetary treatment of PPPs.

A sound appraisal of the project is crucial to bringing quality projects to the market. However, less than one-third of these economies have adopted specific methodologies that ensure consistency across projects. An even smaller percentage make those assessments available online. In turn, the private sector often reports a lack of quality projects in the pipeline as a constraint to invest in infrastructure.

Most economies perform relatively close to recognized good practices in the procurement phase, yet there is still room for improvement. Transparent interaction between the bidders and the procuring authority helps bidders better understand and fulfill the needs of the procurement authority. While most economies allow bidders to submit clarifying questions during tendering, 14 percent of all economies do not require the answers to be disclosed to the rest of the bidders. Only about half (55 percent) of economies hold pre-bid conferences, and most of them allow information from the conferences to be disclosed. Once the private partner has been selected, it is considered good practice to share both the results and the grounds for selection of the winning bidder. While all the OECD high-income economies in the survey require such disclosure, some regions, including South Asia, fall short in this area.

Improvements are still needed in PPP contract management. Given the long-term nature of PPPs, the need for renegotiations may arise, but certain limitations are required to prevent opportunistic behavior by participants. Fifteen percent of the economies do not even address PPP contract renegotiation in their regulatory frameworks. Thirty-one percent consider it a contractual issue, yet do not use standardized contracts to preserve consistency. When contracts must be terminated before the pre-agreed duration, the grounds for termination and its consequences should be specified to reduce contractual risks. However, 35 percent of economies do not regulate either of the issues.

Unsolicited proposals (USPs) need to be properly regulated to prevent nontransparent behavior. A significant number of economies explicitly allow for (57 percent) or prohibit them (3 percent). However, 10 percent of the assessed economies do not regulate USPs, but USPs still take place in practice. This percentage is the highest in the East Asia region (20 percent). The lack of clarity and transparency in the treatment of USPs may lead to projects that yield low value for money. Moreover, when a competitive process is followed for a USP, in 48 percent of the economies, bidders are granted a minimum time to submit their bids that is shorter than for a PPP that is not originated as a USP. In another 34 percent, the minimum time is not even defined.

Most economies adhere to international good practices in terms of disclosure of information to the public in the procurement phase, but do not adopt such disclosure practices during the preparation phase and contract management. Among the assessed economies, it is common practice to publish and make available online the PPP public procurement notice and the award notice. However, only 48 percent of economies publish the PPP contracts during the procurement phase, and even fewer (30 percent) publish any amendments.

Publication of project assessments and tender documents online leads to a greater predictability of the pipeline project quality. However, many economies still do not comply with this practice. Only 22 percent of the economies surveyed publish PPP proposal assessments online, while 60 percent publish PPP tender documents. Moreover, only one-third of the economies have developed standardized PPP model contracts.

Making performance information available to the public increases accountability of all the stakeholders and is crucial to promote transparency. However, few economies make this information public. Transparency ensures that the project delivers the expected outcomes and quality services. However, only a small fraction (13 percent) of the economies surveyed allow public access to the system for tracking progress and completion of construction works under a PPP contract. Only 10 percent have established an online platform for this purpose. Similarly, only a handful of the procuring authorities (14 percent) allow the public to track contract performance through a designated online platform or by posting the updated documentation online.