PPP Regulatory Framework

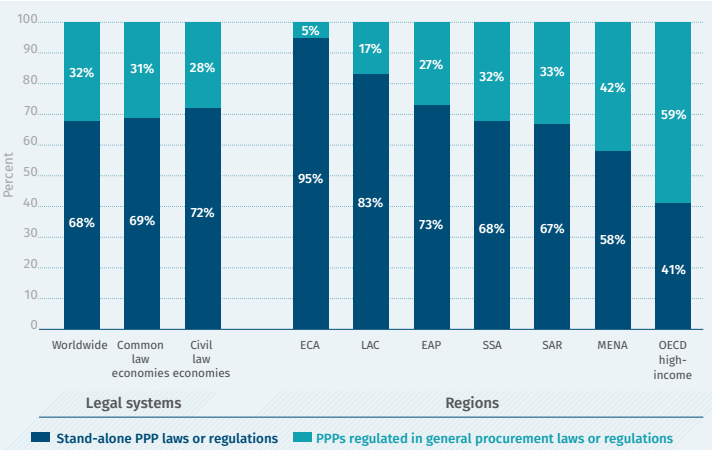

There is no single prescriptive way of regulating PPPs. Governments have used different approaches and this assessment does not presume that one particular legal configuration is preferable to another. Economies around the world have different legal systems, which could affect the type of PPP regulatory framework they adopt. Whereas civil law economies are generally characterized by codified statutes and regulations, common law economies are traditionally less reliant on them. Legal precedents, judicial rulings, or contracts are instead expected to govern PPP projects in common law economies, and thus these economies could be less likely to adopt stand-alone PPP laws. While a wide discrepancy between the two major legal systems might be expected, the data surprisingly show merely a minor difference in the proportion of economies with stand-alone PPP laws and regulations between common law and civil law economies (69 percent and 72 percent, respectively) (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Stand-alone PPP laws worldwide, by legal system and region (percent, N = 135)

Source: Procuring Infrastructure Public-Private Partnerships 2018.

Note: ECA = Europe and Central Asia; EAP = East Asia and Pacific; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; MENA = Middle East and North Africa; PPP = public-private partnership; OECD = Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; SAR = South Asia; SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa.

In the 68 percent of economies that have enacted a stand-alone PPP law, some regional variation emerges. Eastern Europe and Central Asia (ECA) and Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) have the largest proportion of economies adopting a stand-alone PPP law or regulation (95 percent and 83 percent, respectively), while in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) this proportion is just 58 percent. Interestingly, the majority of high-income member countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) do not follow this trend. instead, PPPs are mostly regulated as part of their general procurement laws and regulations. This appears to reflect regionally driven regulatory preferences and possibly the use of PPP stand-alone laws to fill regulatory "gaps." Notably, the Latin American and Caribbean region undertook a wave of reforms in the 1980s and 1990s adopting concessions laws, and a second wave of reforms adopting PPP laws that is ongoing. On the other hand, instead of adopting individual regulation for PPPs, economies in the European Union have more commonly integrated the regulation of PPPs as one type or modality of public procurement.

Following the definition of PPPs used by the project, this categorization is independent of the legal terminology used in a particular economy or jurisdiction to denominate PPPs. For example, Chile uses the legal term "concessions," but in the above categorization is considered to have a stand-alone PPP law. On top of this, however, there is a set of economies that have two alternative separate regimes for PPPs and concessions, independently of whether they regulate PPPs in stand-alone law and regulations or within the broader context of public procurement. This is the case in Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, France, Mauritius, Niger, Russian Federation, Senegal, and Togo (6 percent of the assessed economies).

There are significant nuances in the distinction between economies with stand-alone PPP laws and those that use their public procurement laws and regulations to enact PPPs. For example, in Canada, Georgia, India, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom, PPPs are governed by the same laws and regulations as public procurement, but those economies have developed specific guidelines for the preparation of PPPs as well as standard PPP contracts. Botswana, Ghana, and Nigeria have not yet adopted a stand-alone PPP law, but have developed PPP policies that guide the application of the general procurement framework for PPPs.

Among the economies that have adopted stand-alone PPP laws, Colombia, Greece, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, and Portugal use them only to regulate particular aspects relevant for PPPs and refer to the general procurement laws and regulations for other matters. In Germany, the adoption of a specific PPP law introduced reforms in the existing general procurement laws and regulations that were amended to also regulate the procurement of PPPs specifically. In Azerbaijan, Honduras, and Mali, the PPP stand-alone law expressly excludes the application of the general public procurement laws and regulations for PPPs.

While having a stand-alone PPP law can add clarity to the regulatory framework for the development of PPPs, it is not a guarantee of success. In a similar light, though having a stand-alone PPP law generally has a positive impact on a country's PPP program, the lack of a stand-alone PPP law will not mean a country cannot have a successful program. For example, while a stand-alone PPP law can simplify the regulatory framework, it may also generate legal vacuums if other public procurement regulations do not apply and create uncertainties if introducing inconsistencies with existing legislation. Moreover, the details of each particular PPP should be regulated in the PPP contract. Thus, any of the described legal configurations could be equally successful in creating an adequate environment for the development of PPPs as long as the relevant elements are covered. While some economies have launched important PPP programs based on a stand-alone PPP law (for example, Colombia and the Philippines), many of the economies with more mature PPP markets rely on general regulations complemented by specific PPP guidelines (for example, Australia and the United Kingdom). This is why instead of focusing on the particular legal configuration, Procuring Infrastructure PPPs 2018 focuses on the alignment of specific elements of the framework in a particular country with recognized international good practices.

Between January 1, 2016 and June 1, 2017, 64 of the 135 economies assessed undertook some type of regulatory reform affecting the PPP regulatory framework. In 76 economies, reforms were ongoing and/or are planned after the cutoff date of this report (June 1, 2017). While most of the regulatory reforms have limited impact on this assessment, recent major reforms confirm the trend to regulate PPPs with stand-alone PPP laws. For example, Afghanistan, Argentina, and Pakistan have recently enacted new stand-alone PPP laws. Other economies, such as Madagascar, have complemented previously adopted laws with detailed regulations. A few of the most prominent reforms to the PPP regulatory framework undertaken since the publication of the previous edition of this report are discussed in Box 2.

| Box 2 Several recent prominent PPP regulatory framework reforms Afghanistan: The new PPP Law (approved by Presidential Decree No. 103) and the National Policy on Public Private Partnerships, 2017 published by the Central Partnership Authority were enacted specifically to regulate PPPs in Afghanistan. This new framework aims to establish an enabling environment to attract investment in PPPs that can help Afghanistan face such issues as the "lack of infrastructure, congestion and delays in implementing development projects, overreliance on foreign aid, and poor service delivery." Transparency, accountability, value for money, and affordability are among the principles promoted by the new framework that for example requires using "comprehensive reviews and specific evaluation criteria…to select projects for PPP procurement and to identify the preferred bidder for each project."a Argentina: The new Public-Private Partnership Agreements Law 27,328 and its regulatory decree, Decree No. 118/2017, were approved with the aim of easing and promoting an adequate institutional framework for private investment in infrastructure and services. Among the relevant issues regulated by this new law are the option of establishing alternative dispute resolution mechanisms, including international arbitration, and a more detailed regulation of PPP contract assignment.b However, this new framework creates a new regime outside the scope of the existing regulation of administrative contracts (including concessions), and therefore introduces two alternative avenues to undertake PPPs. This new stand-alone PPP law neither revokes nor replaces the preexisting concession regime. While preserving preexisting regimes for PPPs can add flexibility, it can also diminish clarity and add to the opacity of the regulatory framework, which may in turn provide room for opportunistic behavior. Madagascar: While the PPP Law was approved in 2015, its provisions lacked the level of detail to provide a comprehensive PPP framework. In 2017, two decrees that govern the implementation of the PPP Law were adopted: Decree 2017-149, regarding procurement modalities of PPP contracts; and Decree 2017-150, detailing the institutional framework of PPPs. Among the areas newly covered by these decrees are the requirement to prepare a draft PPP contract, an express specification of the minimum period to submit proposals, and a more detailed regulation of renegotiations. Pakistan: The recently enacted Public Private Partnership Authority Bill, 2017 intends to "provide a regulatory and enabling environment for private participation in provision of public infrastructure and related services."c In addition to establishing the independent Public Private Partnership Authority (PPPA) with advising and gatekeeping roles for the development of PPPs, it also provides a stronger legal basis for many of the areas only contemplated in the 2010 Pakistan Policy on PPPs. For example, the requirement to ensure fiscal affordability is now legally codified, and several steps in the procurement process (including the publication of the procurement notice) as well as dispute resolution mechanisms are now specifically regulated for PPPs. a. Public Private Partnership in Afghanistan: An Alternative to Public Sector Financing, National Policy on Public Private Partnerships 2017, Central Partnership Authority, 4-5, https://www.pajhwok.com/en/opinions/public- private-partnership-afghanistan-alternative-public-sector-financing. b. Argentina: New Legal Framework Allows for International Arbitration and Dispute Boards in Public-Private Partnership Projects, https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=8b23a3ce-ceb4-4dd0-bbd3-05854920fc7b; Argentina: Invest in Public-Private Partnership Projects in Argentina, http://www.mondaq.com/Argentina/x/640672/ Government+Contracts+Procurement+PPP/Invest+In+PublicPrivate+Partnership+Projects+In+Argentina. c. The Public Private Partnership Authority Act, 2017. |