Institutional Arrangements

Given the complexity and relative novelty of PPPs as an approach to deliver infrastructure, governments may need to create specific institutions to support their development. In many economies, the creation of these institutional arrangements is a relevant component of the PPP regulatory framework. While the economies assessed have adopted diverse institutional arrangements to support the development of PPPs, the creation of PPP units is a common trend. Such units can facilitate the development of PPPs by centralizing PPP expertise in a single government agency. However, as with stand-alone PPP laws, the creation of a PPP unit is not in itself a guarantee of success. Furthermore, the practicality of establishing a single centralized PPP unit is contingent on the size and administrative structure of each economy. Consequently, once again, while this element provides necessary context and a basis for the rest of the analysis, it is not scored.

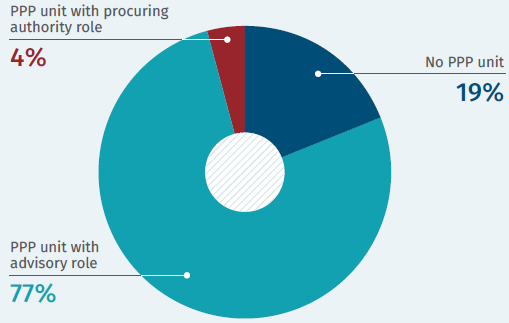

Eighty-one percent of the assessed economies have a dedicated PPP unit. Some are independent organizations akin to other governmental departments, such as the Public and Private Infrastructure Investment Management Center (PIMAC) in the Republic of Korea and the Infrastructure Concession Regulatory Commission (ICRC) in Nigeria. In other cases, the PPP unit is part of a larger ministerial or departmental structure. In Jamaica, for example, the PPP unit is located within the Development Bank of Jamaica, and in Turkey it is under the General Directorate of Investment Programming, Monitoring and Assessment of the Ministry of Development.

While the role and functions of the PPP units vary, most PPP units have a common set of core tasks: PPP regulation policy and guidance (in 85 percent of the economies with a PPP unit); capacity building for other government entities (in 88 percent); promotion of the PPP program (in 88 percent); technical support in implementing PPP projects (in 80 percent); and oversight of PPP implementation (in 75 percent). These functions are consistent with the PPP unit performing mainly an advisory role supporting the actual procuring authorities (usually the relevant line ministry). In addition, around 59 percent of the PPP units are also required to approve PPP projects, usually through their participation in the PPP feasibility assessment process. Finally, the assessment of the fiscal risks borne by the government in a PPP is not usually a function attributed to the PPP unit but instead left directly to the Ministry of Finance or central budgetary authority.

Figure 3 PPP unit's role in the procurement of PPPs (percent, N = 135)

Source: Procuring Infrastructure Public-Private Partnerships 2018.

Note: PPP = public-private partnership.

In a handful of economies (4 percent) (see Figure 3), the PPP unit plays a more prominent role in the development of PPP and acts as the main (or exclusive) procuring authority for PPPs. This is the case, for example, in Chile (where Coordinación de Concesiones procures public works concessions in agreement with the line ministries); Honduras (where Coalianza is the main actor in the procurement process for PPPs); Ireland (where procurement of PPPs is centralized through the National Development Finance Agency, NDFA); Peru (where ProInversión acts as procuring authority for large PPP projects); and Kuwait (where the Kuwait Authority for Partnership Projects, KAPP, takes a leading role in the procurement of PPPs identified by line ministries). While this arrangement may support a more efficient development of PPPs by centralizing procurement in a single unit with expertise in PPPs, it may also take that role away from the line ministries that are ultimately responsible for the delivery of infrastructure. About one-third of the existing PPP units participate in the task of identifying and selecting PPP projects, but this task is more commonly undertaken by the procuring authorities themselves.