Fiscal Treatment of PPPs

When entering into PPP contracts, governments may incur fiscal commitments such as direct liabilities (like availability payments or shadow tolls) and contingent liabilities (such as guarantees or compensation clauses) whose occurrence, timing, and value depend on some uncertain future events. Without those liabilities being accounted for (through public financial management), PPPs can be used to bypass budgetary and fiscal controls and become a hidden burden to the public sector, affecting the overall fiscal sustainability of the economy.

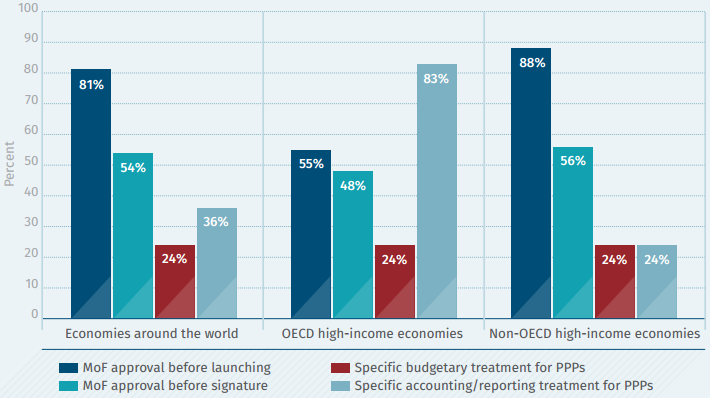

Despite the relevance of this issue, appropriate assessment of the fiscal implications of PPPs is still not common practice. A large majority of the surveyed economies (81 percent) require an approval by the Ministry of Finance or the central budgetary authority before embarking on the PPP procurement process. However, only 54 percent of all surveyed economies require an additional approval before the PPP contract is signed. This second approval can be important to ensure that the project is still fiscally affordable for the government after any significant changes that may have occurred during the tendering process (Figure 7).

The type of approval by the Ministry of Finance varies across economies. In a majority of the assessed economies that require an approval, the regulatory framework expressly requires the approval of the Ministry of Finance itself (examples include Belarus, Indonesia, and Paraguay). However, in 18 percent of the economies, this approval is only implicit: for example, the Ministry of Finance reviews and approves the PPP project as part of an approval committee (as in Angola, Bangladesh, and Jordan).

In some economies, the approval process is selective. The Ministry of Finance is required to vet a PPP project only when it requires budgetary funds. This is the case, for example, in Albania, Bulgaria, and Mongolia. Such a differentiation tends to create incentives to financially structure PPP in a way that such controls are avoided, instead of structuring them optimally.

Regulations are even less precise when it comes to specific provisions regarding budgetary, accounting, and/or reporting treatment for PPPs. Only 36 percent of the economies have introduced some type of regulatory provision regarding the accounting and/or reporting treatment of PPPs and even fewer (24 percent) have specific provisions about the budgetary treatment for PPPs.

The budgetary treatment provisions take different modalities, but in general they imply an express recognition of the long-term impact of PPP liabilities. For example, in Austria, the Federal Budget Law imposes specific budgetary requisites25 to execute projects that involve obligations in future fiscal years. Similarly, in Mexico, the future commitments required by the PPP must be defined and calculated following the provisions of the Federal Budgeting and Fiscal Responsibility Law (LFPRH).

Without requiring a specific budgetary treatment for PPPs, a number of economies have developed alternative mechanisms to control the budgetary implications of PPPs. For example, Argentina, Burkina Faso, Colombia, Ecuador, Honduras, Madagascar, and Paraguay have introduced limitations to the total amount of funds that can be committed to PPP projects. While limitations of this type control the potential fiscal impact of PPPs more tightly, they may also impose undue restrictions for the development of necessary and optimal PPP projects. On the other hand, in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, the Republic of Korea, and Uganda, the regulatory framework provides for the creation of a viability gap fund. Such funds help PPPs achieve commercial viability and aim to centralize the provision of public support to this end.

Specific provisions for the accounting and/or reporting of PPPs are also uncommon. These provisions regulate, for example, which party assumes the debt related to the PPP on its balance sheet and/or require the government to disclose information on the potential fiscal impact of PPPs. OECD economies that are members of the European Union are subject to the common European System of Accounts (ESA), which provides for a specific treatment of PPPs. This requires the public sector to account for PPP-related debt if it retains a substantial part of the risk in the PPP project. Other than this, only a handful of other economies (less than 5 percent) have adopted the International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS) as their model for the accounting treatment of PPPs. IPSAS require a PPP to be considered as part of the public sector balance sheet if the public sector retains overall control of the project. This is the case in Chile, Peru, South Africa, and Turkey.

An interesting pattern emerges from the data when comparing high-income OECD economies to developing economies (Figure 7). The regulatory frameworks in non-OECD economies place great emphasis on formal approvals by the Ministry of Finance or the central budgetary authority, leaving less discretion with the procuring authorities but also introducing an extra layer of formal approval. However, in those same economies, provisions concerning budgetary and fiscal treatment are rare. In contrast, in high-income OECD economies, formal approvals by the Ministry of Finance are not as commonly required (leaving more discretion, but also more responsibility with the procuring authorities), but a larger proportion of those economies have adopted specific provisions regarding accounting for PPPs as a fiscal control mechanism.

Figure 7 Fiscal treatment of PPPs (percent, N =135)

Source: Procuring Infrastructure Public-Private Partnerships 2018.

Note: MoF = Ministry of Finance; OECD = Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; PPPs = public-private partnerships.