Disclosure of the PPP Procurement Process Results

The tendering process concludes with the selection of a winning bidder. Providing information to bidders and publishing decisions helps build confidence in the fairness and transparency of the process while preventing occurrence of fraud and corruption and obtaining value for money through a competitive process. In addition, making data on the outcome of the tendering process readily available to all the bidders by expressly informing them through an intention to award notice has the potential of increasing private sector participation in the oversight process. Finally, when bidders have information concerning the intent to award the contract, including the grounds for awarding the winning bid, they will have a clear picture of the details surrounding the procurement process, which can allow them to file a complaint if they are aggrieved by the decision of procurement authority.

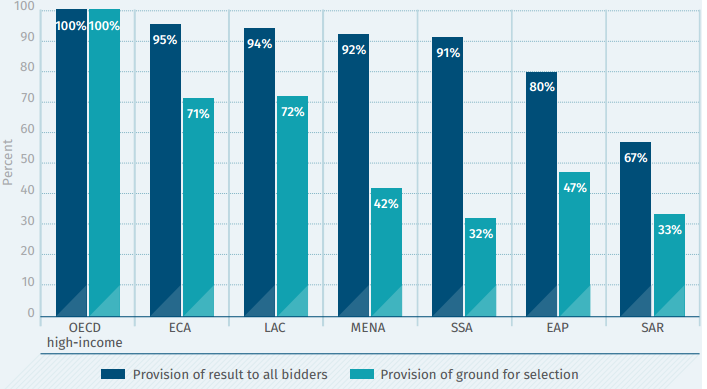

The first step in the disclosure process is to share the intent to award decision notice with all bidders. To ensure full disclosure, the notification of the results should also include the grounds for awarding to the winning bid(s). As seen in Figure 10, the provision of the PPP procurement process results, and information about the grounds for awarding the winning bidder, vary by region. Procuring authorities in all 29 OECD high-income economies share both the result of the procurement process and the grounds for awarding the winning bidder with all bidders who have participated in the tender. The OECD high-income region leads in this area, followed by Europe and Central Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean. On the other hand, only 67 percent of the economies in the South Asia region are required to provide the results of the procurement process to bidders, and only about 33 percent must include the grounds for awarding to the winning bid. Bangladesh, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Mongolia, and Zambia are among the economies that are not required to provide such results.

Disaggregating the data by income level clearly reveals that the lower the income group level, the less information about the PPP procurement results is disclosed (ranging from 100 percent in OECD high-income economies to 50 percent in low-income economies).

Failure to include the grounds for awarding to the winning bidder means that not enough information about the relative advantages of the successful tender is disclosed, and therefore, the bidders would have to inquire about the reasons for the rejection of their proposals. This process can be time consuming, impractical, and burdensome for the unsuccessful bidders who wish to challenge the procedure and the result of the procurement process. Afghanistan, Belarus, Côte d'Ivoire, Sri Lanka, United Arab Emirates, and Zimbabwe are among those economies that provide bidders only with the result of the procurement process, without disclosing the grounds for the selection of the winning bid.

Figure 10 Disclosure of PPP procurement results, and grounds for selection by region (percent, N = 135)

Source: Procuring Infrastructure Public-Private Partnership 2018

Note: OECD = Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development; ECA = Europe and Central Asia; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa; MENA = Middle East and North Africa; EAP = East Asia and Pacific; SAR = South Asia.

Another important element of the procurement process is the standstill period. Once the intent to award to the winning bidder for a tender is announced, a reasonable period of time must elapse between the time when unsuccessful bidders are notified about the intent to award the contract to the winning bidder and the contract is actually awarded. This allows a window of opportunity for unsuccessful bidders to challenge a contract award before the PPP contract signing and execution phase starts. This is particularly important in economies where an annulment of the PPP contract is not possible, or when a complaint does not trigger a suspension of the procurement process. A reasonable standstill period makes it possible for the unsuccessful tenderer to examine the validity of the award decision as well as any flaws that may have occurred during the evaluation process, and to ensure that a challenge to such an award decision will be effective. Finally, the standstill period is not only beneficial to the bidders for the reasons discussed, but it is also beneficial to the procuring authority because it provides a clearer framework for bidders to challenge the award decision. Although the aggrieved bidders can always initiate a procurement challenge after the contract is awarded, a standstill period usually precludes the possibility of declaring the ineffectiveness down the line, preventing the most serious and costly post-contractual remedy.

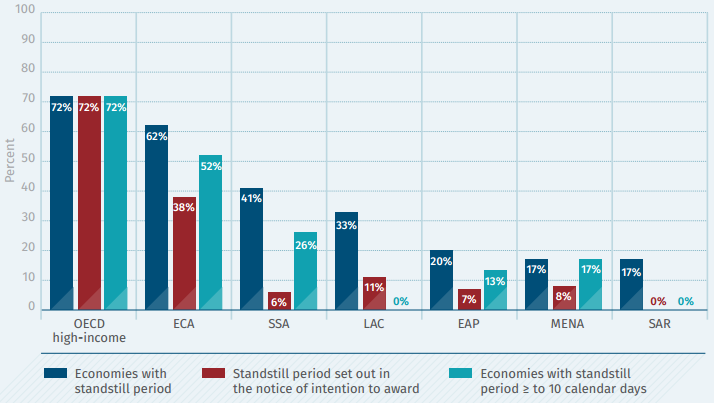

The highest number of economies providing a standstill period in their legal and regulatory frameworks are in the OECD high-income region (72 percent), compared to only 17 percent in South Asia (where only Sri Lanka does so). This trend could be explained by the fact that all members of the European Union (EU) are required to have a pause period between the notification of the award decision and the signature of the PPP contract to be compliant with the EU Directives.28 Outside of the European Union, economies like Armenia, Kenya, and Russian Federation also provide for a standstill period to challenge the award. On the other hand, bidders in economies such as Nigeria, Qatar, Sierra Leone, Vietnam, and Zimbabwe do not have standstill safeguard in their PPP regulatory framework.

Figure 11 The standstill period (percent, N = 135)

Source: Procuring Infrastructure Public-Private Partnership 2018

Note: OECD = Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development; ECA = Europe and Central Asia; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa; MENA = Middle East and North Africa; EAP = East Asia and Pacific; SAR = South Asia.

To optimize its effectiveness, the standstill period should be set out in the notice of intention of award, to inform aggrieved bidders about the timeline available for them to challenge the decision of the procuring authority. Seventy-two percent of OECD high-income countries include the standstill period in the intention of award, compared to none of the economies in South Asia. In addition, a reasonable window of time should be available to allow sufficient time for aggrieved bidders to decide whether they want to challenge the award and submit a complaint. A minimum of 10 days is a recognized standstill period, as reflected in judgments by the European Court of Justice, the World Trade Organization's Government Procurement Agreement, and other binding texts.29 Legal frameworks that set shorter periods, such 5 days (Angola, and Nicaragua) or 7 days (Belarus) do not necessarily offer aggrieved bidders enough time to prepare and submit an efficient challenge. The regional comparison reveals an interesting contrast (Figure 11). While 72 percent of the OECD high-income economies provide a standstill period of at least 10 days, all (100 percent) of the economies in the Latin American and Caribbean and South Asia regions have standstill periods of less than 10 days.

| Box 5 Transparency throughout the PPP life cycle Openness and transparency throughout the life cycle of a public-private partnership (PPP) are essential to maximize efficiency gains in infrastructure and to assure optimal socioeconomic outcomes. The availability of information in the public domain increases predictability, boosts public confidence in PPP projects, reduces the risk of corruption, and ensures alignment of private investments with public interest. Most experts agree that transparency in PPPs can be achieved through proactive disclosure of information to the public. Procuring Infrastructure PPP 2018 reveals considerable areas for improvement in the proactive disclosure of information, especially at the preparation and contract management stages of the PPP life cycle. Figure 12 presents the Procuring Infrastructure PPP 2018 transparency scores by scoring selected questions referred to transparency and aggregating them by thematic areas (Appendix 3).30 While at the procurement stage, the global average of the Procuring Infrastructure PPP 2018 transparency score is 66, this global average drops to 38 during the preparation stage and to only 12 points during the contract management stage. This average score indicates that it is relatively easy to obtain information surrounding the bidding process, for example, but project assessments remain mostly unavailable in the public domain and public tracking of PPP contracts performance remains cumbersome or even impossible in many jurisdictions. Figure 12 Transparency scores, by area and income-level group (score 1-100)

Source: Procuring Infrastructure Public-Private Partnerships 2018. Note: PPP = public-private partnership. There is also a significant divergence in the adherence to the good transparency practices across income levels. Figure 12 shows that the higher the income level of the group, the higher their performance in terms of transparency practices-with significant room for improvement for all income groups in project preparation and contract management. At the preparation stage, high-income economies reach an average transparency score of 54 points, while low-income economies attain only 18 points. The lowest level of transparency across income groups is observed in the contract management phase, where high-income economies score as few as 12 points, upper-middle-income countries score 17, and lower-middle-income countries score 13. None of the low-income economies follow the good practices at the contract management stage. At the preparation stage, publication of project assessments and tender documents online leads to greater predictability of the pipeline project quality, instilling confidence in the public and investors, and thereby minimizing risks. Despite these benefits, only 22 percent of the economies surveyed publish PPP proposal assessments online. Over half of the countries surveyed (60 percent) publish PPP tender documents and only about one-third (36 percent) have developed standardized PPP model contracts and/or transaction documents (Figure 13). Figure 13 Transparency in the PPP project cycle (percent, N = 135)

Source: Procuring Infrastructure Public-Private Partnerships 2018. Note: PPP = public-private partnership. At the procurement stage, transparency and wide dissemination of the main decisions regarding the selection of the private partner enables all stakeholders to be fully informed. Potential bidders will readily know when PPP projects are on the market and know the results of the selection process undertaken. More importantly, this information will also be in the public domain, fostering accountability of the procuring authorities, and thus discouraging corrupt practices and hasty decisions. All the economies surveyed, with the exception of Papua New Guinea, publish a PPP public procurement notice and 88 percent make it available online. Some 93 percent of the surveyed economies publish the award notice, and, 82 percent make it available online (Figure 13). This relatively common practice of publishing the PPP tender and award notice contrasts with the proportion of economies that publish the PPP contract: only 48 percent of the economies publish the PPP contract, 38 percent make it available online, and even fewer economies (30 percent) publish amendments to the PPP contracts. At the contract management stage, promoting transparency is essential. Making performance information available to the public increases accountability of all the stakeholders. Transparency ensures that the project delivers the expected outcomes and quality services. However, only a small fraction (13 percent) of the economies surveyed allow public access to the system for tracking progress and completion of construction works under a PPP contract. Only 10 percent of them have established an online platform for this purpose. Similarly, only a handful of the procuring authorities (14 percent) allow the public to track contract performance through a designated online platform or by posting the updated documentation online. |