Renegotiation or Modification of the PPP Contracts

While predictability is important for all parties to a PPP agreement, a degree of flexibility is just as crucial. When elements of the procured project evolve, this flexibility should allow for those changes to be addressed, preferably within the clearly defined internal mechanisms established in the contracts or, when absolutely necessary, by amending the agreement accordingly. The term "renegotiation" refers to changes in the contractual provisions other than through an adjustment mechanism provided for in the contract.32 The intrinsically incomplete nature of PPP contracts implies that, sometimes, required renegotiations may generate positive results. Nonetheless, renegotiation should be limited to prevent opportunistic behavior.33 Given the partnership nature of PPP projects, such amendments should be balanced to preserve all stakeholders' rights and obligations, as well as the public interest. Unilateral contract amendments and arbitrary decisions by the procuring authority undermine the partnership element of PPPs, violating the legitimate expectations of the private partner. This could not only hinder the project at hand but also deter future PPP projects. Thus, strong deterrents for these instances of abuse of power by the procuring authorities should also be contained in the PPP agreement, along with further contract management measures.

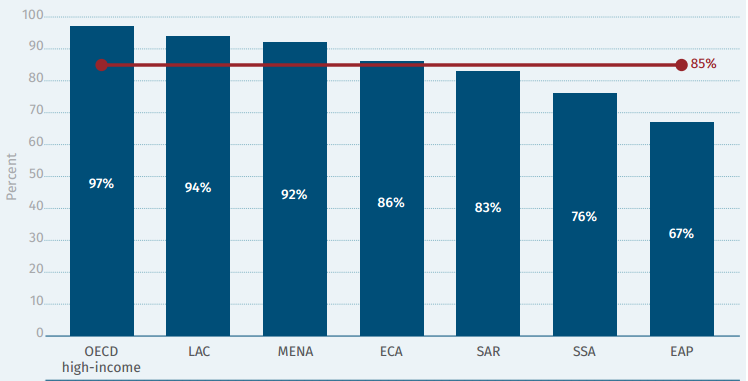

Only about 15 percent of the economies measured do not regulate PPP contract modifications.34 Armenia, Lebanon, Malawi, Papua New Guinea, and Tonga are among the countries where the modification of contracts is left to the discretion of the procuring authority. There are significant regional differences. While in the OECD high-income region 97 percent of the economies regulate PPP contract modification, only 67 percent of economies in the East Asia and Pacific region do so (Figure 15).

Figure 15 Regulation of renegotiation, by region (percent, N = 135)

Source: Procuring Infrastructure Public-Private Partnerships 2018.

Note: ECA = Europe and Central Asia; EAP = East Asia and Pacific; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; MENA = Middle East and North Africa; PPP = public-private partnership; OECD = Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; SAR = South Asia; SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa.

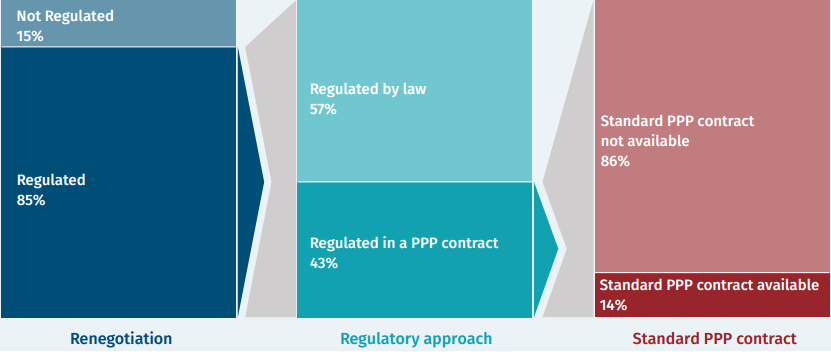

Regulatory approaches with respect to renegotiation vary among the 85 percent of the economies that regulate PPP contract modifications. About 57 percent of those economies have detailed provisions in the regulatory frameworks, such as restrictions to change the scope of the PPP contract or alter its economic balance or amend the agreed risk allocation. Bulgaria, Latvia, Mali, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, the Philippines, and Serbia are among the economies with detailed provisions. The remaining 43 percent considers renegotiation to be a contractual issue, allowing parties to further regulate its aspects in the contractual agreement. Benin, Burundi, Indonesia, Kyrgyz Republic, Macedonia, Timor-Leste, and Turkey are a few examples of the latter case (Figure 16).

The lack of standard provisions for renegotiations for the parties in the PPP contract could mean that approaches to renegotiation remain ad hoc and consistency is not preserved. This gap may be filled by standardized PPP contracts that guide parties through the renegotiation process while still allowing them flexibility to address the project's specific needs. However, among the countries that consider renegotiation a contractual issue, only 14 percent clearly use standardized contracts, including India, Japan, Kazakhstan, and South Africa.

Figure 16 Regulatory approach to renegotiation (percent, N = 135)

Source: Procuring Infrastructure Public-Private Partnerships 2018.

Note: PPP = public-private partnership.

PPP contract modification could also be safeguarded by other means. Sound regulation of any amendment to the PPP contract during execution of the project phase should entail a transparent approval process and collaboration among institutions, which will guarantee that procuring authorities do not have sole discretion over contract renegotiation powers.

Approval measures ensure that the outcomes of the projects are not later disturbed by an unfettered renegotiation process. Of the economies that regulate modifications to the PPP contract, 55 percent require approval of such modifications by a government entity other than the procuring authority. In 35 percent of those economies, approval by the Ministry of Finance is required if the amendments imply that a public body will assume increased direct financial liabilities. This is the case in Croatia.35 Djibouti goes even further in terms of institutional approvals of amendments to PPP contracts by requiring a preliminary approval by the procuring authority, which must also be submitted for approval to the Council of Ministers after the PPP unit has ensured that such amendments do not change the nature of the project or substantially affect the essential features of the project.36 In Ecuador, approvals of all amendments are obtained by an inter-institutional Committee called the Comité Interinstitucional de Asociaciones Público-Privadas.37 And in Nicaragua, because any PPP contract amendment must be approved by law, approval by the National Assembly is also required.38

| Box 7 Unilateral modification of PPP contracts While PPP contract parties may jointly agree to modify the PPP agreement after its signature, regulations may also permit unilateral amendments by the procuring authority. There should be, however, limits and specific circumstances to enact such amendments. These parameters include necessary external approvals, restraints to certain substantive material changes in the contract, and compensation when the private partner incurs damage or costs.39 Of the 135 economies measured by this assessment, only 24 percent of them (33) permit unilateral amendments to PPP contracts. There are significant regional differences. None of the economies in the East Asia and Pacific and South Asia regions permit unilateral amendments, while 56 percent of the economies in Latin America and the Caribbean do so (Figure 17). While the majority of economies (94 percent) that permit unilateral amendments set limitations to this prerogative, Burundi and Cameroon do not have clear limitations to unilateral contract modification powers or an approval process as a safeguard. Figure 17 Possibility of unilateral modification of PPP contracts, by region (percent, N = 135)

Source: Procuring Infrastructure Public-Private Partnership 2018 Note: OECD = Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development; ECA = Europe and Central Asia; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa; MENA = Middle East and North Africa; EAP = East Asia and Pacific; SAR = South Asia. Economies with civil law legal systems, such as Algeria, Colombia, Costa Rica, France, Kazakhstan, and Senegal, often refer to general principles of administrative law that permit such unilateral amendments. In addition, in Uruguay, for example, the PPP contract may provide for the right for the procuring authority to unilaterally modify the PPP contract, within a limit of 20 percent of the original budget of the project.40 In Togo, such circumstances should consider "an evolution in the procuring authority's needs, technological innovations or modifications in the financing conditions obtained by the private partner."41 Spain, on the other hand, allows unilateral amendments if such amendments serve the public interest, with the requirement of preserving the economic balance of the contract.42 In Saudi Arabia, amendments to works covered by the contract as well as increasing or reducing the contractor's obligations are within the "competency of the government authority," with certain safeguards. When exercising such powers, the procuring authority must ensure that the additional works fall within the scope of the contract, that such modifications serve the public interest, and that the economic balance and nature of the contract will be preserved.43 |