The Regulatory Framework of USPs

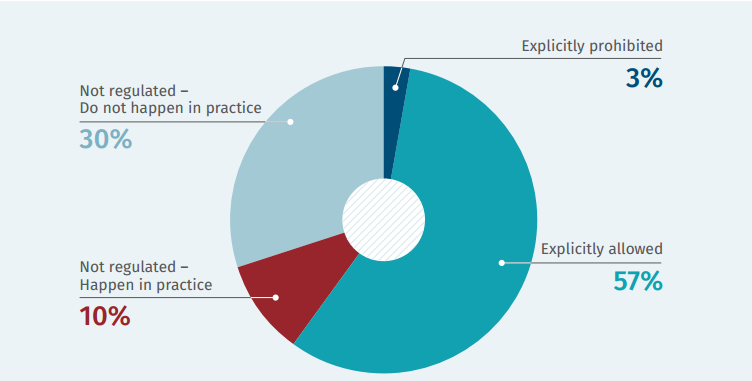

Among the 135 economies that are covered by the Procuring Infrastructure PPPs 2018 project, there are significant differences in the manner that USPs are regulated. Figure 20 shows that in 57 percent of economies covered by the project, the regulatory framework explicitly allows and regulates the use of USPs. This is the case in economies such as Australia, Chile, Ghana and Japan. At the other end of the spectrum, in 3 percent of the economies (namely, in Botswana, Croatia, Germany, and India), the use of USPs is explicitly prohibited by the regulatory framework. In 40 percent of the economies covered by the project, the regulatory framework does not discuss or regulate in any way the instances where a private proponent can approach the government with infrastructure proposals. In most of these cases, USPs do not happen in practice, according to local contributors. In fact, while not expressly forbidden in the regulatory framework, the lack of a specific regulation can be construed as a prohibition in practice, since PPP procurement methods are limited to those expressly regulated. This is the case for example in Canada, the United Kingdom, and most other EU economies.

In 24 percent of the economies that do not regulate USPs (or 10 percent of the total), projects originated through USPs still occur, according to local contributors. Examples include Chad, Myanmar, and Trinidad and Tobago. In these cases, the lack of a clear framework applicable to USPs implies that they can become a method to circumvent procurement rules that ensure adequacy, transparency, and fairness. This may result in developing projects that are not in the public interest.

Figure 20 USP regulatory framework (percent, N = 135)

Source: Procuring Infrastructure Public-Private Partnerships 2018.

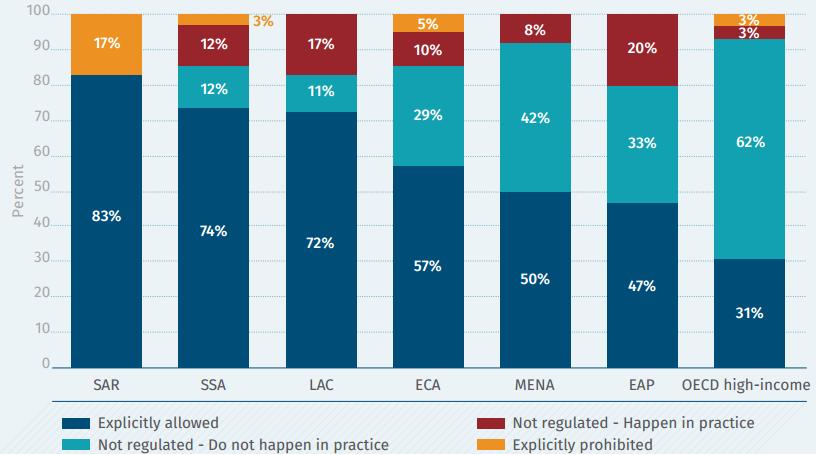

USPs are regulated differently across regions. Figure 21 shows that in 83 percent of the economies in South Asia, USPs are explicitly allowed by the regulatory framework. This is in contrast with the East Asia and Pacific and Middle East and North Africa regions, where USPs are explicitly allowed in only 47 percent and 50 percent of the economies, respectively. Moreover, East Asia and Pacific has the largest percentage of economies where USPs happen in practice despite not being regulated (20 percent). According to the Policy Guidelines for Managing Unsolicited Proposals in Infrastructure Projects published by the World Bank in 2017,59 "Many governments lack the technical expertise and experience to develop projects successfully from beginning to end, or they lack the financial resources to hire external advisors to support them in developing and procuring projects. Countries with limited public-sector capacity typically rely on USP proponents to develop the projects, in return for which the USP proponents typically expect the projects to be awarded to them." Accordingly, it is not surprising to find that low-income economies, such as Afghanistan, Guinea, and Uganda, are more likely to have regulatory frameworks that specifically allow the use of USPs. On the contrary, in the majority (62 percent) of OECD high-income economies, where the regulatory frameworks remain silent regarding this matter, USPs do not take place in practice.

Figure 21 USP regulatory framework by region (percent, N = 135)

Source: Procuring Infrastructure Public-Private Partnerships 2018.

Note: Some numbers in the figure may not add up due to rounding. ECA = Europe and Central Asia; EAP = East Asia and Pacific; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; MENA = Middle East and North Africa; OECD = Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; SAR = South Asia; SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa; USP = unsolicited proposal.