Competitive Bidding and Minimum Time Limits

By having a clear and comprehensive competitive procedure in place for evaluating and managing USPs, governments can reduce the pressure from the private sector and special interest groups to accept USPs. In addition, a competitively tendered USP project is more likely to result in a well-structured PPP contract that maximizes value for money.60 The lack of transparency and not using a competitive procedure carries the risk of increasing corruption and can lead to the development of projects that are unsuitable and low quality, and provide low value for money.61

Interestingly, all the economies that either explicitly allow the use of USPs or conduct USPs in practice require a competitive procedure62 for government-initiated PPP projects. However, only 83 percent of them require that a USP be procured using a competitive mechanism. Some of the economies that do not require a competitive procedure for procuring USPs include the Republic of Congo, Guinea, and Moldova. Moreover, differences among income-level groups are cause for concern; low-income economies and lower-middle-income economies are more likely not to require competitive procedures. Among the economies that do not require USPs to be procured using a competitive procedure are Chad and Rwanda (low-income countries), as well as Djibouti and Vietnam (lower-middle-income countries).

Approximately 66 percent of economies that conduct USPs mandate that some minimum amount of time should be given to additional bidders (those that did not initiate the USP) to prepare and submit their bids, including China, Côte d'Ivoire, Kazakhstan, and the Philippines. It is important to provide bidders with an adequate amount of time to prepare and submit their bids. It is even more important when the project originated as a USP because otherwise, the original proponent has an unfair advantage in the competitive bidding process. Therefore, in such cases, governments, at a minimum, should adopt the same policies/time that they use for the regular procurement procedure. Interestingly, 7 percent of economies that conduct USPs, including Gabon, Papua New Guinea, and Togo, do not provide bidders a minimum amount of time to bid in either a regular procedure or a USP procedure. In Cambodia, the government provides bidders with a minimum time to prepare their bids for USPs, but the specific period of time is set by the procuring authority.

Even in cases where a minimum amount of time is provided, it must be adequate for additional bidders to submit their bids.63 According to the World Bank Policy Guidelines for Managing Unsolicited Proposals in Infrastructure Projects, a low number of days gives the original USP proponent an advantage when submitting bids and could deter competition by discouraging additional proponents from submitting their bids. Furthermore, the guidelines state that "competing bidders must be given sufficient time to prepare a competitive bid and must have timely and equal access to all relevant information about the project."64 The guidelines also note that in some economies that gives 60 days for additional bidders to prepare their bids with a right to match mechanism, such as the Philippines, the majority of the projects that originated as a USP resulted in the original USP proponent winning the bid.65 Moreover, private entities emphasize that they need at least three to six months to "develop a serious competing proposal."66 Still, only 12 percent of economies, such as Jamaica, the Republic of Korea, and Tanzania, provide additional bidders with 90 days or more to submit their bids. The most common option (among 31 percent of economies, including Nigeria, Ukraine, and Uruguay) is to provide a minimum time of between 30 to 59 days. Such a period may not be sufficient for addition proponents to prepare adequate bids. The World Bank guidelines also state that "providing a short period for competing bidders to submit bids (usually less than six months) limits competition." However, in only one of the economies, Colombia, bidders are granted six months (180 days) as minimum legal time to prepare bids.

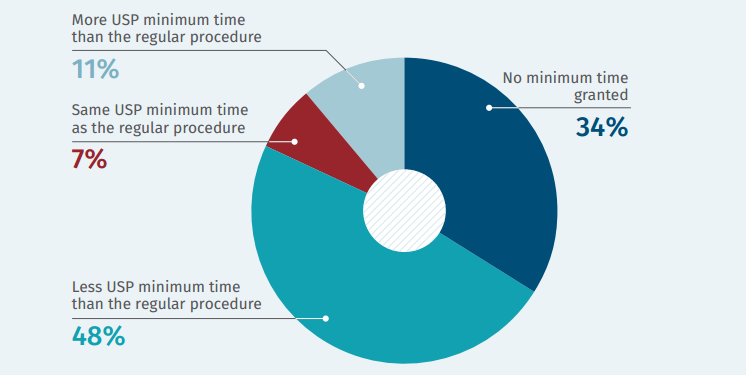

Finally, given that the original proponent has a head start in preparing the proposal and bidding documents, the World Bank guidelines recommend that additional proponents should be given at least the same amount of time, if not more, in the case of a USP procedure as compared to a regular PPP procedure. However, as Figure 22 shows, in 48 percent of economies, bidders are granted a minimum time that is shorter when the project originated as a USP procedure than in a regular PPP procurement procedure. These economies include Nigeria (30 days instead of 42 days) and the Philippines (60 days instead of 90 days). Only 11 percent of economies provide more time when the projects were originated as a USP. This includes economies such as Jamaica (90 days instead of 30 days); the United States, Commonwealth of Virginia (120 days instead of 60 days); and Russian Federation (45 days instead of 30 days).

Figure 22 Comparison of Minimum number of days between regular and USP procedure (percent, N = 90)

Source: Procuring Infrastructure Public-Private Partnerships 2018.

Note: The category "Same USP minimum time as the regular procedure" also includes the economies that specify a minimum time for both a regular and competitive procedure in their regulations, but do not specify the actual amount of time for either. The category "More USP minimum time than the regular procedure" also includes economies that mandate a minimum time for a USP procedure, but do not mandate it for a project initiated by the government. USP = unsolicited proposal.