Structural Fragmentation

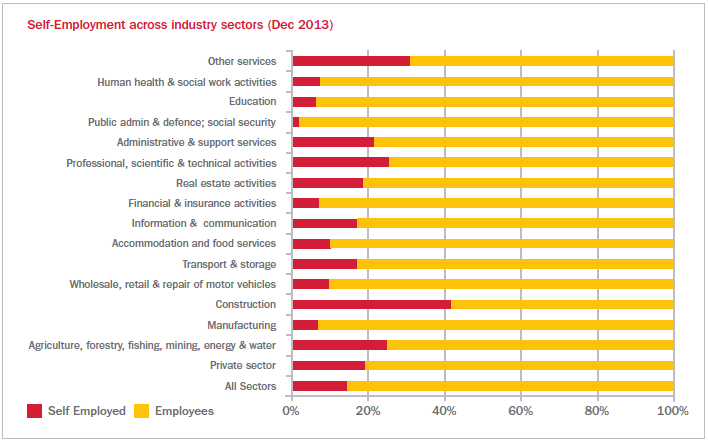

The construction industry is often characterised as an example of 'market failure'. This usually refers to its highly fragmented structure (both vertically and horizontally), introverted nature and unusually high levels of self employment (see Figure 6).

A Review of Industry Training Boards7 published by BIS in December 2015 referenced 40% of total construction contracting jobs as being self-employed compared with 15% across the whole economy.

The structural make-up of the industry and its organisational separation from clients is an important defining characteristic of construction, which differs from other more collaborative industries. Contractors and their supply chain tend to have limited involvement with clients upfront in the feasibility stage of a project.

The lack of integration across the supply chain, manifested in a wide-scale use of sub-contracting and tiered transactional interfaces is commonplace. This has created significant non value add costs in the supply chain through multiple on-costing, downward and often inappropriate risk transfer. This leads to an industry that tends to be cost-focused rather than value-focused.

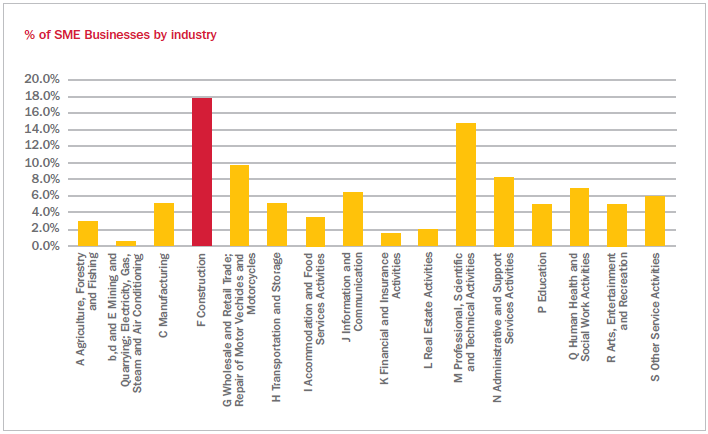

There is a high volume of SME businesses in the construction industry with just under a fifth of all SMEs working in construction8 at the start of 2015 as shown in Figure 7.

In addition, there is little evidence of corporate overseas new entrants coming into the core UK construction market and directly competing with the large domestic 'tail' of the industry. The CBI reported in July 2015, Fit for the Future: Strengthening Construction Supply Chains9, that 93% of the UK construction supply chain is sourced domestically. This confirms the high barriers to entry for corporate level importation of physical construction activity (i.e. productive labour as opposed to management or plant and material supply).

A natural consequence of fragmentation is that those tiers of the industry closest to clients or indeed forming parts of clients' organisations themselves have effectively become process managers for a wider cascaded supply chain rather than having direct delivery control by employing their own workforce.

Figure 6: From Combined Triennial Review of Industry Training Boards (Construction, Engineering Construction and Film), Department of Business, Innovation and Skills, December 2015

Figure 7: from Business Population Estimates for the UK and Regions 2015, Department of Business, Innovation and Skills, October 2015.

In this regard, the terms 'housebuilder' and 'contractor' are now potentially misnomers as the physical delivery is largely done by others. 'The Homebuilding Supply Chain Research Report'10 published in October 2015 indicated that housebuilders subcontract the majority of construction work to their supply chain; in most cases this was 90-100% of the work. The residual management and supervision deployed by these organisations is the only chance to drive value for their clients and themselves. Often this is hampered by distance from the broad components of a supply chain that might include designers and other consultants, as well as specialist and non-specialist sub-contractors and a multitude of suppliers.

The recent advent of employment intermediaries or umbrella companies has further cascaded reluctance to directly employ labour down the supply chain and increased the distance between employment and the top tier transactional interface and between the end client and industry.

The lack of control and organisational proximity to resource is exacerbated in times of high demand as fragmentation is compounded by high levels of itinerant self-employed labour not fully controlled by those owning contractual responsibility for outcomes, even two to three levels down the supply chain.

There are few examples where the industry or indeed clients have looked to vertically integrate their supply chain through either single point ownership or much stronger collaborative cross-corporate alliances as seen in other industries. Where there have been moves in this direction, they are often seen as a last ditch response to poor industry performance. Such approaches are often viewed suspiciously by others as an exception to the unwritten rule that the industry is defined by its flexibility and lack of willingness to hold a large work force or fixed cost investments. This review heard evidence in a few isolated instances of a desire from certain large main contractors and housebuilders to increase the proportion of their directly employed PAYE trade workers, mostly in response to concerns over labour security in the future. However, this is not a widespread trend and is certainly yet to be evidenced in practice.

Recent indicators suggest some structural disruption to this 'accepted' model in the UK (see Case Studies 2 and 10). This approach is being challenged by a few isolated client or industry participants that are able and willing to move to a higher level of self-delivery and direct control over the wider built asset creation process.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

7 Combined Triennial Review of Industry Training Boards (Construction, Engineering Construction and Film), Department of Business, Innovation and Skills, December 2015.

8 Business Population Estimates for the UK and Regions 2015, Department of Business, Innovation and Skills, October 2015.

9 Fit for the Future: Strengthening Construction Supply Chains. CBI, July 2015.

10 The Case for Collaboration in the Homebuilding Supply Chain. CITB, HBF, Skyblue, October 2015.